Scientists report huge leap towards integrating holograms into cell phones

Holograms projected through mobile phones has always seemed like an idea straight out of science fiction. However, physicists have now built a compact optical device with the ability to project detailed holographic pictures.

Instead of needing thousands of tiny pixels, this system can form a holographic image using light from just one pixel. That scale makes holography feel much closer to future phones and wearables.

Holograms from one pixel

A hologram can show depth and subtle detail in a scene. That kind of image needs very careful control over how light leaves the display.

The work was led by Ifor Samuel, a professor of physics at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. His research focuses on light based devices made from carbon rich materials for displays, sensors, and medical tools.

Using a single controllable light source to draw a full pattern means the holographic hardware can be much simpler than current displays.

An organic light emitting diode, a flat light source used in phone screens and shortened to OLED, provided the light in the new setup.

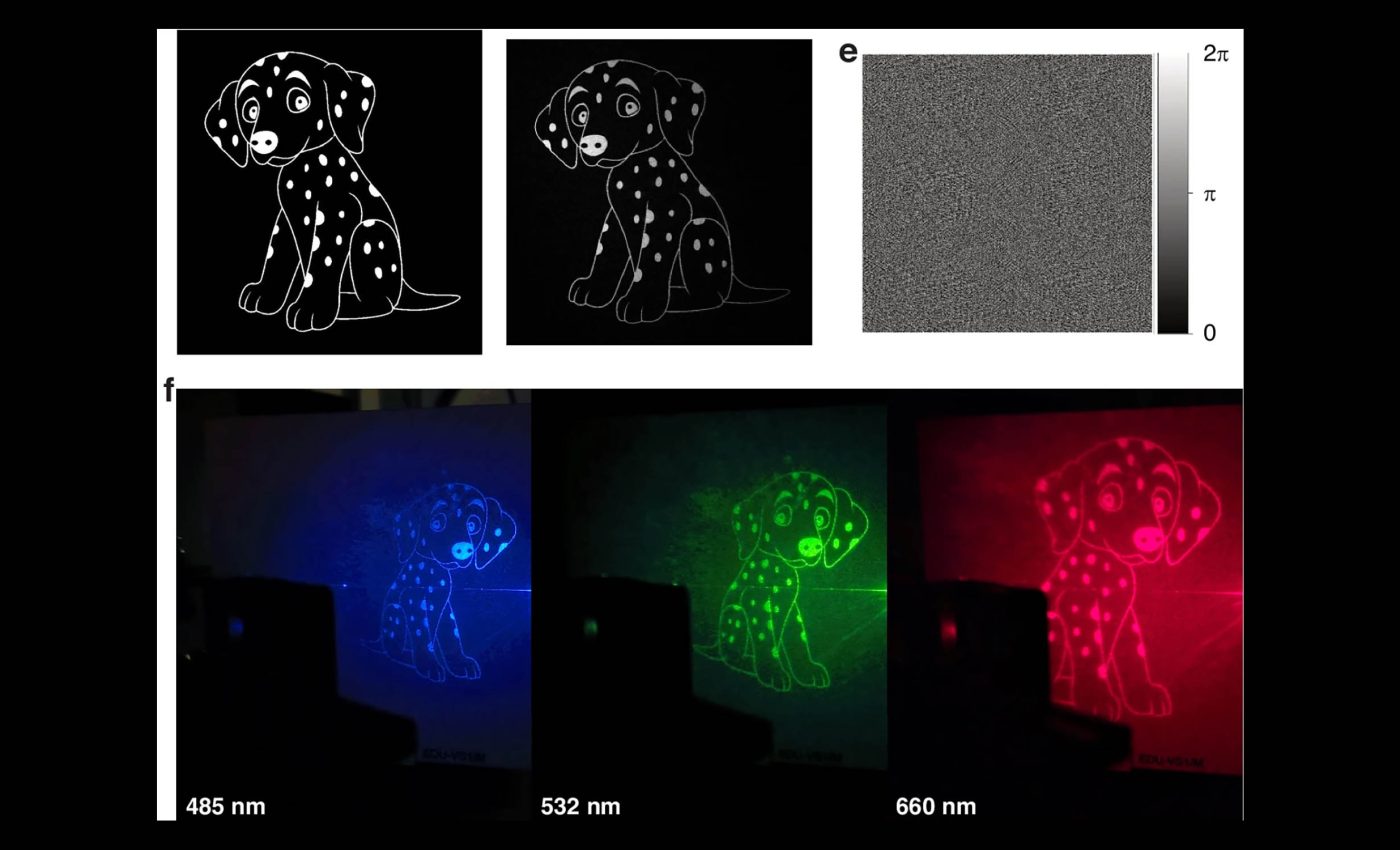

In that experiment the source shone through a patterned glass chip and formed a holographic picture of a Dalmatian dog.

Understanding OLEDs

Each OLED pixel is a tiny stack of organic materials that light up when current passes through. Today that design powers most high end phones and many premium televisions, turning electricity straight into colored light without a separate backlight.

Because OLED panels are thin and emit light across their surface, they are useful wherever engineers want large flexible light sources. Those qualities also make them a natural partner for tiny structures that steer light in precise ways.

Physicists often talk about spatial coherence, a measure of how well different parts of a light beam stay in step. Ordinary OLED pixels have low spatial coherence, so their light normally blurs together instead of forming sharp interference patterns.

Laser sources usually win for holography because their light is highly coherent, which keeps fine details intact over distance. Finding a way for an OLED pixel to feed a hologram without a laser is therefore a big technical shift.

How metasurfaces reshape light

The patterned glass chip in this study is a metasurface, a layer covered with tiny features that bend and delay light. By designing those features carefully, researchers can make the outgoing light form almost any target image in space.

In the St Andrews device, each nanostructure acts like a tiny pixel that slightly shifts the phase of the light passing through it.

When many of these pixels are organized into the right pattern, interference between their beams produces a designed holographic image on a screen.

“Holographic metasurfaces are one of the most versatile material platforms to control light,” said Andrea Di Falco, a nanophotonics researcher at St Andrews. He sees that versatility as key for future holographic devices.

Turning a lab into a tiny projector

In the lab, the team placed the OLED and metasurface facing each other inside a dark box so no stray light leaked in. They tuned the wave pattern by sliding the light source a couple of inches closer or farther from the metasurface.

The researchers also added a color filter between the OLED and the metasurface to narrow the range of red wavelengths reaching the chip.

That filter shrank the emission bandwidth from 63 nanometers down to 10 nanometers, which made the Dalmatian hologram clearer across the picture.

With the filter in place, fine lines in the projected pattern could be as narrow as about one hundredth of an inch. The speckle contrast, a measure of grainy noise in holograms, dropped to 0.23 compared with 0.81 for a display driven by a laser.

To isolate the role of color spread, the team replaced the OLED with a tunable laser and illuminated the metasurface with selected wavelength sets.

As they narrowed the range of colors around 660 nanometers, image quality measures showed that the holograms became sharper and closer to the design.

The filtering results show that the metasurface forms clearer pictures when the light is coherent and concentrated into a slim part of the spectrum.

Those conditions help each pixel of the structure contribute a well defined piece of the final wavefront instead of washing out the pattern.

Holograms, phones, and the future

Metasurface based optics have already been used to build experimental eyepieces for augmented reality headsets that squeeze lenses and combiners into millimeter scale thickness.

One such eyepiece used a metasurface metalens to widen the field of view while keeping the glasses compact and see-through.

The St Andrews result adds an OLED based light engine, showing that metasurfaces do not always need laser illumination to draw complex images.

That shift opens the door to holographic modules that could sit behind a phone screen or inside glasses and run from ordinary display drivers.

Plenty of challenges remain before anyone can swipe open a holographic phone, including boosting brightness, adding full color, and shrinking the optics even further.

Engineers need to figure out how to manufacture metasurfaces over large areas at low cost without losing the features that control the light.

Even so, the idea that one carefully designed pixel and a nanostructured surface can paint a hologram hints at a new class of display.

The study is published in Light: Science & Applications.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–