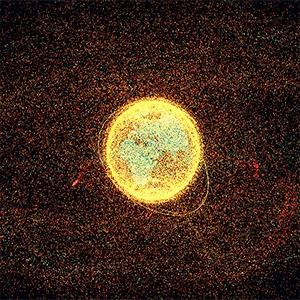

Space health score reveals that Earth’s orbit is in serious crisis

Space is filling up with junk fast. Nearly 30,000 tracked pieces of debris are orbiting Earth right now. And that doesn’t include hundreds of thousands of smaller fragments that are too tiny to monitor. They are certainly still dangerous enough to damage a satellite or space station.

All this junk poses a serious risk. If we don’t keep space clean, future missions – weather satellites, aGPS systems, internet services, even space travel – debris could knock missions off course or shut them down completely.

A scorecard for space health

To get a grip on the chaos, the European Space Agency has come up with something new: a space environment health index. This single score shows how healthy – or stressed – Earth’s orbit will be over the next 200 years.

Why 200 years? Because space junk doesn’t go away on its own. It lingers, circles the planet at high speed, and adds to the risk of collisions for decades or even centuries.

The new index is designed to sum up the long-term impact of current space activities in one number.

“The space environment health index is an elegant approach to link the global consequences of space debris mitigation practices to a quantifiable impact on the space debris environment,” said Stijn Lemmens, space debris mitigation analyst at ESA.

“With the new metric, ESA is promoting a common language for assessing the impact of our space activities and making consequences concrete.”

Breaking down the score

The index doesn’t only count how many satellites are launched. It also looks at key factors that influence how much risk a mission adds to the orbital environment.

These factors include the size and shape of the object, how long it will stay in orbit, and whether it can maneuver to avoid crashes. In addition, the index considers what steps are taken to prevent an object from exploding after its job is done, and the chance it might break apart into more debris.

All of these factors are turned into a score that reflects how much a mission adds to the risk of future collisions or junk. In this case, a low score means a mission won’t add much trouble, whereas a high score means the opposite.

Think of it like an energy-efficiency label for a fridge. In the future, satellite missions could be rated A to F for how clean they are in space.

Space health is already compromised

Scientists initially set the baseline for a “healthy” orbital environment using international guidelines from 2014.

Back then, even with best practices, the future was already looking three times riskier than the minimum level considered sustainable.

Today, the situation is worse. We are now four times over the safe threshold at health index level 4. That means our orbit is significantly overcrowded and moving toward instability, despite better efforts by many satellite operators.

Why this score matters

The new index isn’t just for tracking progress. It can actually shape decisions before a mission is launched.

For example, the index can be used during the design phase to make sure a satellite’s orbit is short, its disposal system works, and its risk of breaking up is low. That helps reduce its score and encourages better practices.

“Even if the definition of the health index may seem very theoretical, at ESA we have already successfully applied this concept in practice,” said Francesca Letizia, space debris mitigation engineer at ESA.

“We had to evaluate different policy options to define the Zero Debris approach. We used the health index model to translate the mandate for a Zero Debris approach into numbers, identifying a path that would not exceed the orbital sustainability threshold.”

Regulators could use the index for licensing. Insurance companies could factor it into risk assessments. And mission designers could aim for lower scores the same way carmakers aim for better fuel economy.

Space doesn’t clean itself

Some people might shrug and say the worst-case scenario is 200 years away. Why rush? The danger builds up fast. Every new satellite adds to the pile.

Every breakup event adds more junk. And cleaning it up isn’t easy or cheap. The longer we wait, the harder and more expensive it becomes to fix.

Long before space becomes completely unusable, the cost of operating in it will spike. Certain orbits might become no-go zones. And crewed space missions could face even more risk from debris traveling faster than bullets.

That’s why ESA’s Zero Debris goal – stopping all debris generation from its missions by 2030 – isn’t just a nice idea. It’s a necessity.

The space environment health index gives space agencies, governments, and companies a tool to work with. It shows what’s working, what’s not, and how to make better decisions for the future of orbital health.

The space junk above our heads may be out of sight, but it’s not out of mind. And now, finally, it’s measurable.

Information from a press release by the European Space Agency.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–