Stone tools created 400,000 years ago show tech advancement of early humans

Archaeology sometimes feels like detective work with a very long timeline. Every chip of flint or shard of bone builds a narrative of how early humans used tools to feed themselves, cooperated, and thought about the places they called home.

Fresh finds from two sites just northeast of today’s Tel Aviv – Jaljulia and Qesem Cave – add an eye-opening chapter to that story.

They point to a moment, roughly 400,000 years ago, when hunters in the Levant not only pivoted to new prey but also redesigned their tools and, perhaps, their beliefs.

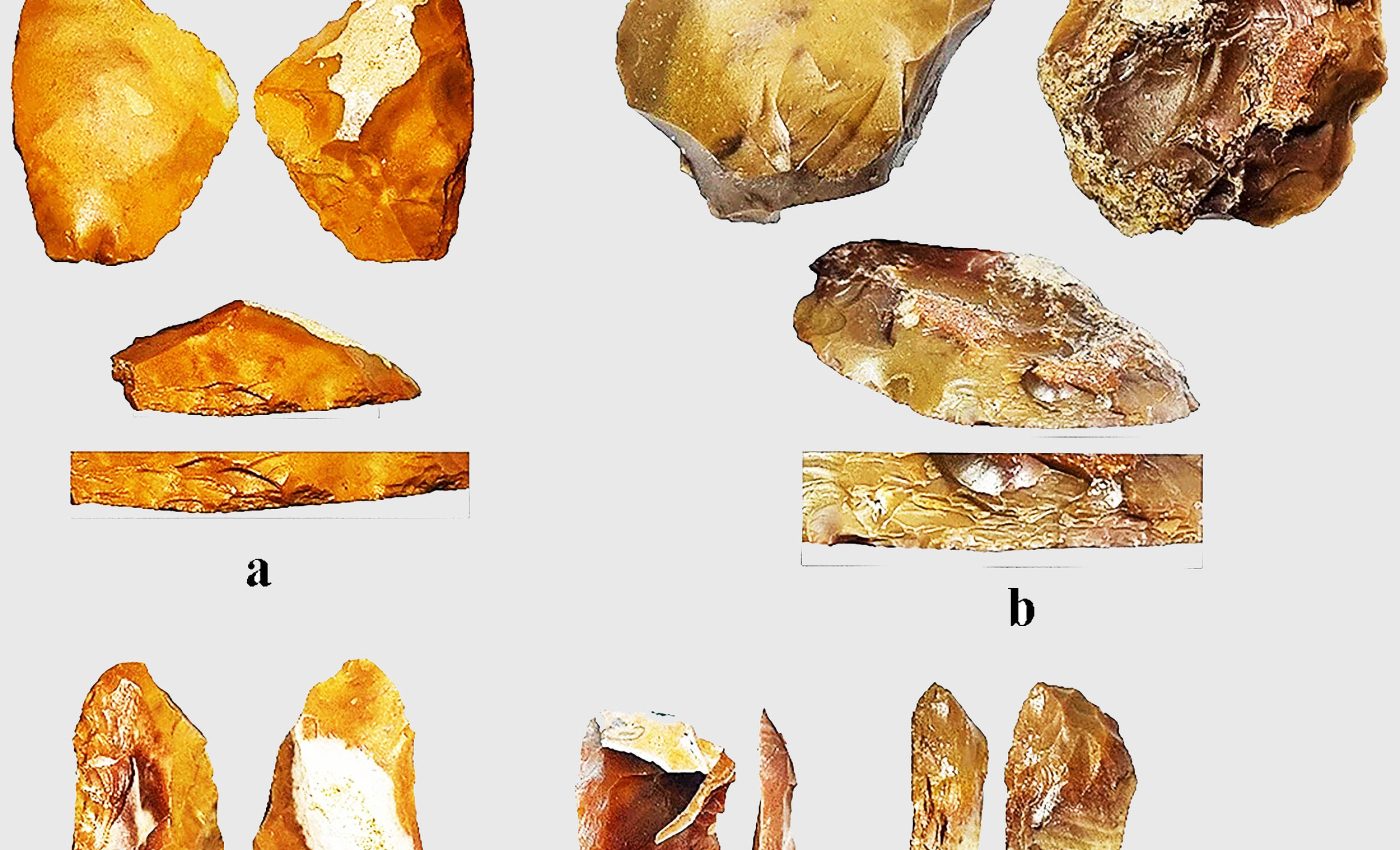

The discoveries revolve around a specialized flint implement known as a Quina scraper.

At first glance the artifact looks modest – smaller than a modern smartphone. Its scalloped edge, though, is razor-sharp, built for slicing through muscle and hide with an efficiency that would have impressed any butcher.

Flint tools and shifting appetites

For nearly a million years, large game dominated dinner menus here – especially elephants that roamed plains stretching from Africa into Eurasia.

When those giants dwindled, hunting parties had to recalibrate.

The speedier, leaner fallow deer offered far less meat per kill, so hunters needed to process many more carcasses to match the calories once supplied by a single elephant. That change forced a rethink of both strategy and gear.

Fallow deer thrived in mixed woodlands along what are now the Samarian highlands. Their bones fill layers in Jaljulia and Qesem Cave, signaling a dietary shift that mirrors broader environmental turnover during the late Lower Paleolithic.

Tools carved with flint for venison

Enter the Quina scraper. Unlike earlier, more rudimentary scrapers, this one features a stepped, scale-like working edge that holds a keen bevel.

Microscopic wear marks reveal repeated motions suited to neatly removing skin and sinew. The stone tool design likely spared hunters valuable time at the kill site, reducing exposure to scavengers and rival predators that could steal a hard-won carcass.

Modern experiments with replicas confirm that the tool excels at producing long, clean strips of hide – ideal for lashing shelters, wrapping meat, or even tailoring early garments.

A single scraper could be resharpened several times, making it a portable workhorse on multi-day forays.

Stone from sacred hills

The most unexpected twist lies not in the tool’s shape but in its raw material. Quina scrapers at both sites were made of flint hauled roughly 12.4 miles from the western slopes of the Samarian mountains, bypassing closer outcrops.

That same upland served as a calving ground for fallow deer. Hunters, then, were linking an essential resource – flint – to the very landscape that provided their new staple food.

The study’s lead authors – Vlad Litov and Prof. Ran Barkai of Tel Aviv University – spell out what that pairing means.

“In this study we tried to understand why stone tools changed during prehistoric times, with a focus on a technological change in scrapers in the Lower Paleolithic, about 400,000 years ago,” Litov explained.

Forced to hunt smaller animals

We found a dramatic change in the human diet during this period, probably resulting from a change in the available fauna: the large game, particularly elephants, had disappeared, and humans were forced to hunt smaller animals, especially fallow deer.

Clearly, butchering a large elephant is one thing, and processing a much smaller and more delicate fallow deer is quite a different challenge.

Systematic processing of numerous fallow deer to compensate for a single elephant was a complex and demanding task that required the development of new implements.

“Consequently, we see the emergence of the new Quina scrapers, with a better-shaped, sharper, more uniform working edge compared to the simple scrapers used previously,” Litov added.

Tech advancement shown in flint tools

Prof. Barkai explains that the study reveals “links between technological developments and changes in the fauna hunted and consumed by early humans.”

While previous theories credited advancements in stone tools to biological evolution, he and his team suggest a “double connection, both practical and perceptual.”

Practically, tool sophistication evolved to meet the demands of hunting smaller, faster prey. Perceptually, Barkai points to a symbolic association between specific locations and resources.

“We found a connection between the plentiful source of fallow deer and the source of flint used to butcher them,” he notes.

Prehistoric hunters seemed to favor flint from the same region where the deer roamed – Mounts Ebal and Gerizim – suggesting a deep-rooted awareness of the landscape and its significance.

“This behavior,” he adds, “is familiar from many other places worldwide and is still widely practiced by native hunter-gatherer communities.”

Why does any of this matter?

According to Litov, the Mountains of Samaria held deep significance for prehistoric people living at Qesem Cave and Jaljulia.

“We believe that the Mountains of Samaria were sacred to the prehistoric people… because that’s where the fallow deer came from,” he says.

As elephant populations declined, early humans in the region shifted their focus to fallow deer. Tools made from a variety of local stones have been found at Jaljulia, but something unique occurred when they began sourcing both their prey and tool-making materials from the Samarian highlands.

“Identifying the deer’s plentiful source, they began to develop the unique scrapers in the same place,” Litov explains.

These specialized tools – first appearing in Jaljulia around 500,000 years ago – later spread more broadly, showing up at Qesem Cave between 400,000 and 200,000 years ago.

Archaeological evidence, including fallow deer bones from Mount Gerizim and other sites, suggests that the area supported deer populations well into the Holocene.

“Apparently, the Mountains of Samaria gained a prominent or even sacred status as early as the Paleolithic period,” Litov concludes, “and retained their unique cultural position for hundreds of thousands of years.”

Prehistoric man was smarter than we thought

Pairing a resource with a place crops up again and again in human history, from obsidian quarries in the American Southwest to jade rivers in ancient China.

The Jaljulia and Qesem Cave findings push that behavior deep into the past, showing that meaning and material were already intertwined long before written lore. Technology did not change in a vacuum; it mirrored environmental stress and social imagination.

Understanding how early communities adapted to shrinking megafauna offers a cautionary parallel for modern ecosystems losing key species. Innovation can soften the blow, but it also reshapes culture in ways that echo far beyond survival.

A humble flint scraper, carried miles across rugged ground, reminds us that tools are never just tools. They are signatures of what people value, where they find sustenance, and how they make sense of their world.

The full study was published in the journal Archaeologies.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–