Strange new shrimp that swims upside down seen for the first time living in a pond

A shallow roadside pool in India’s Western Ghats looks ordinary at first glance. Cattle wade in, tourists stop for a breather, and below the surface small creatures go about their business.

That humble scene now has a surprising cast member, a newly described fairy shrimp whose life plays out in warm, temporary water that often dries up between seasons.

The animal’s entire known world fits inside a pool about 20 feet by 10 feet and a little over 3 feet deep.

The discovery was reported by Avinash Isaac Vanjare and Prashant Manohar Katke of Ahmednagar College in Maharashtra (ACA), with coauthor Sameer M. Padhye.

Streptocephalus warliae

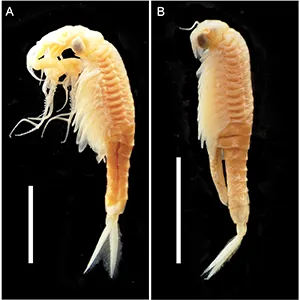

Researchers named the species Streptocephalus warliae and published the description on July 24, 2025, noting unique features of its head appendages and reproductive anatomy. The average body length is 19.1 millimeters, which is about 0.75 inch.

Males carry a distinctive triangular projection at the base of the second antenna’s distal segment, and females show a deep notch at the tip of the second antenna.

The eggs are spherical and about 180 micrometers wide, with raised ridges and depressed centers.

The animal’s proportions fall comfortably within the range for its group, but the shape and armature of those antennae are the giveaways that it is something different.

That combination sets it apart from related South and Southeast Asian species described in earlier work.

Life of a temporary pool resident

Fairy shrimp belong to Anostraca, a group of crustaceans that characteristically swim upside down in ephemeral pools that appear after rain and vanish in the dry season.

They propel themselves with leaflike legs while feeding on microscopic particles.

The upside down posture is not a stunt. It positions their limbs and mouthparts for efficient feeding near the water’s surface, where fine detritus and algae concentrate.

“Streptocephalus warliae sp. nov. is so far known only from its type locality,” wrote the study authors. The site sits on the Jawahar plateau in Maharashtra, a lateritic highland dotted with seasonal rock pools.

Measurements at the pool tell a simple story. The basin is roughly 20 feet by 10 feet and about 3.3 feet deep, with water temperatures around 72 to 75 degrees Fahrenheit, a pH between 7.2 and 7.4, and salinity near 27 to 36 parts per million.

Other residents share the space, including aquatic beetles, submerged plants, and tadpoles. Cattle use the pool for drinking and bathing, and travelers pause at its edge during drives through the plateau.

Streptocephalus warliae needs protection

“We suggest a red listing of the species,” wrote Vanjare. That call reflects a basic reality of small, isolated habitats: one misstep can erase a species.

Large branchiopods across Asia are still underexplored, and many regions have not been surveyed with modern tools, which complicates risk assessment for animals that can disappear before we even know they exist. Urbanization and land conversion add pressure to these transient waters.

The Western Ghats are recognized globally for high endemism and conservation value, which raises the stakes for tiny specialists restricted to a single site. Every new find tightens the link between small pools and regional biodiversity.

What makes this species stand out

The key traits of Streptocephalus warliae are precise and anatomical rather than flashy. The male’s second antenna bears that triangular basomedial projection, and the terminal structures split into rami with a sharp angle and a specific pattern of spines and pustulations.

Females carry an elongated second antenna with a deep apical notch and a brood pouch extending across several abdominal segments.

These characters, taken together, separate the species from lookalikes that occupy different rock substrates in nearby districts.

A hotspot with many gaps

Rocky outcrop pools in Maharashtra support diverse large branchiopods, and surveys have shown several species partitioning habitats across lateritic and basaltic substrates.

That fine scale sorting may limit overlap and make each pool type important in its own right.

Asia’s large branchiopod record still shows blank spaces on the map. New sampling efforts continue to turn up species in places where people have looked for decades for larger animals but missed short lived crustaceans that flash into existence with the rains.

Culture in a scientific name

The species honors the indigenous Warli community that lives in and around the type locality.

Warli art is traditionally executed with rice paste and gum on a red ocher background, a practice closely tied to seasonal rituals and everyday life.

Naming a species after a local community sends a clear signal about where attention belongs. Conservation starts with the people who know the land and its waters best.

A tiny pool looks dispensable until it becomes the whole world for a species. The habitat’s size and shallowness, measured in feet rather than miles, make it both accessible and fragile.

The animal’s eggs can persist through dry spells, waiting for the next rain to return the pool to life. That strategy hedges against drought, but it does not protect against concrete, quarrying, or contamination.

Next steps for Streptocephalus warliae

The authors note that additional genetic data will help clarify relationships among species that look similar but split along habitat lines.

Integrative work that pairs DNA with morphology can reveal hidden diversity and guide local protection.

Long term monitoring is the practical step on the ground. If the pool changes, careful records will show when and how, and that evidence can support swift action.

The study is published in Zoosystematics and Evolution.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–