Student who discovered the pulsar changed astronomy forever

On November 28, 1967, astronomy graduate student Jocelyn Bell Burnell at Cambridge spotted a tiny repeating mark on miles of radio data. That odd signal turned out to be from the first known pulsar, an ultra dense stellar corpse that sweeps radio beams past Earth.

The discovery came from data captured by a radio telescope, an instrument that collects faint radio waves from space.

In this case, Jocelyn Bell Burnell had helped to build the telescope, which consisted of 120 miles (193 kilometers) of tangled wires sprawling across frames in a field.

That strange infrastructure would let astronomers time pulses from dead stars with astonishing accuracy and would quietly rewrite ideas about how stars end.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell and pulsars

The work was led by Jocelyn Bell Burnell, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge, and her research focused on radio sources in space.

Before the odd signal appeared, Bell Burnell spent years helping to construct and run the unwieldy instrument in the Cambridgeshire countryside.

The telescope, officially part of the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory, used long rows of simple antennas instead of a single, giant metal dish.

Instead of recording digital feeds, she watched the sky through paper charts that, rolled out together, would stretch nearly three miles (4.8 kilometers).

Each chart carried the twitchy signature of radio noise from space, mixed with familiar interference from cars, transmitters, and mechanical glitches.

Most of that clutter looked ordinary, but one small smear kept reappearing in exactly the same place on the sky map.

Bell Burnell and ‘LGM’

Bell Burnell later recalled realizing that her brain kept whispering that she had seen that strange blot somewhere on earlier charts.

After checking earlier records, she found the same repeating pulses and nicknamed the source LGM, short for little green men.

She presented the puzzling traces to her supervisor, Antony Hewish, who at first worried that such a faint blemish was just yet another kind of interference.

Hewish suggested verification using a faster recorder. This instrument initially remained stubbornly silent while Bell Burnell’s telescope picked up the intriguing pulses, 1.3 seconds apart.

After what seemed like an interminable wait, the faster telescope also caught a string of pulses 1.3 seconds apart from that patch of sky. Bell Burnell described the discovery in a later Cambridge interview.

From pulses to pulsars

Bell Burnell soon located three more repeating sources in different directions on the sky, which made an artificial origin, including alien transmitters, increasingly unlikely.

In early 1968, she and her colleagues described the first four objects in a paper that established the pulses came from fixed points in our galaxy.

The strange new sources did not match any known star, because their regular flashes were faster than ordinary stellar vibrations or orbital motion could explain.

At first, some scientists imagined oscillating white dwarfs or unfamiliar planets, but the growing catalog of pulses pointed toward something even more extreme inside collapsed stars.

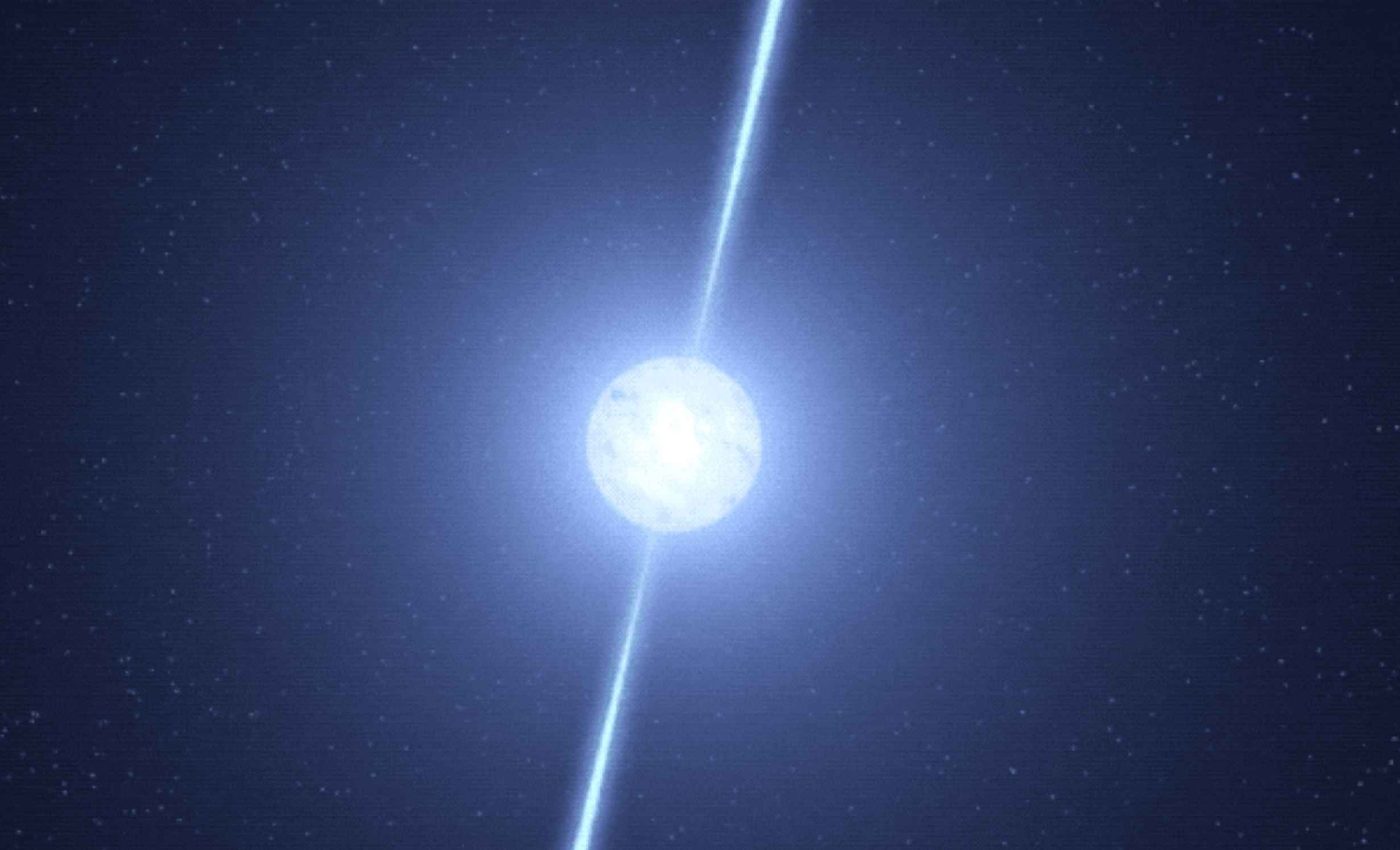

Soon after, theorist Thomas Gold proposed a rotating model in which the mysterious pulses were produced by an exceptionally compact star. That compact object is now understood as a neutron star, an ultra dense stellar core left when a massive star explodes.

Why pulsars matter to physics

In Gold’s rotating model, the star spins rapidly while its intense magnetic field, a region controlling charged particles, is tilted off axis.

Every turn sends a narrow beam of radiation past Earth, so telescopes detect a steady train of flashes with astonishing regularity.

By the early 1970s, astronomers had cataloged over a hundred such objects, and timing measurements showed that their pulses remained stable over long periods.

In his Nobel lecture, Antony Hewish described how these signals functioned as extraordinarily reliable clocks powered by rotating neutron stars, known as pulsars.

Because each pulse arrives at a predictable moment, researchers can use pulsars to track subtle motions and measure the thin gas that fills the space between stars.

That information gives physicists clues about matter crushed to densities far beyond anything that laboratories on Earth can produce.

Lessons from Jocelyn Bell Burnell

According to the official summary, the physics prize went in 1974 to radio astronomers Martin Ryle and Antony Hewish for work that included discovering pulsars.

Bell Burnell’s name was absent from the announcement, even though she had been the person who first noticed and carefully tracked the peculiar signals on the charts.

She later noted that colleagues dubbed it the “No Bell prize” and said she felt proud that her stars had persuaded physicists to recognize serious astronomy.

Her story became a touchstone in conversations about how scientific credit is allocated, particularly for people from groups historically pushed to the margins.

Half a century later, she received a three million dollar Special Breakthrough prize, honoring her early discovery and decades of leadership in astronomy.

She chose not to keep that money, instead directing it into scholarships for women, underrepresented minorities, and refugees who wanted to study physics.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–