The leap that will change computational physics

Physicists have found a way to run Monte Carlo simulations for certain complex materials in a practical amount of time.

Their new method attacks systems where every part feels the pull of every other part, a nightmare for traditional algorithms in large simulations.

In tests on model magnets and particle fluids, tasks that once looked completely out of reach now run on ordinary clusters.

The work comes from a German research team and it targets the hardest cases in computational physics known today.

Monte Carlo simulations

The work was led by Wolfhard Janke, professor of theoretical physics at Leipzig University in Leipzig, Germany.

His research focuses on Monte Carlo simulations, computer experiments based on random sampling.

Many materials do not just interact with their nearest neighbors but also with faraway partners through long-range interactions, forces that decay slowly with distance.

Gravitational systems, charged plasmas, and dipolar magnets all fall into this category, and they often show unusual collective behavior.

To follow the evolution of such a system, a standard Monte Carlo algorithm must consider how every particle interacts with every other particle.

That cost grows as computational complexity, a rough measure of how work scales with size, proportional to the square of the particle number.

Even modestly sized test problems are already brutal for today’s hardware. For familiar models like the Ising and XY spin systems or Lennard Jones fluids, straightforward long range simulations can stall on supercomputers.

Smart use of Monte Carlo simulations

Janke’s group builds on the classic Metropolis algorithm, a simple rule for accepting or rejecting random trial moves.

Their idea is to reorganize how the algorithm computes the energy difference, without changing the physics it samples.

Instead of summing every interaction exactly, the new method groups distant particles or spins into boxes and keeps track of strict energy bounds.

By refining only the boxes that actually matter for each move, the algorithm achieves an average cost that grows like N log N.

The authors report speedups of more than ten thousand compared with a naive long range Monte Carlo implementation.

In practice that means simulations which would have tied up a supercomputer for centuries can now be completed in a matter of days.

Crucially, the method generates exactly the same sequence of configurations as the standard code, so existing observables stay valid.

The team has already applied it to long range Ising and XY spin models and to a Lennard Jones particle system in two dimensions.

Watching systems relax

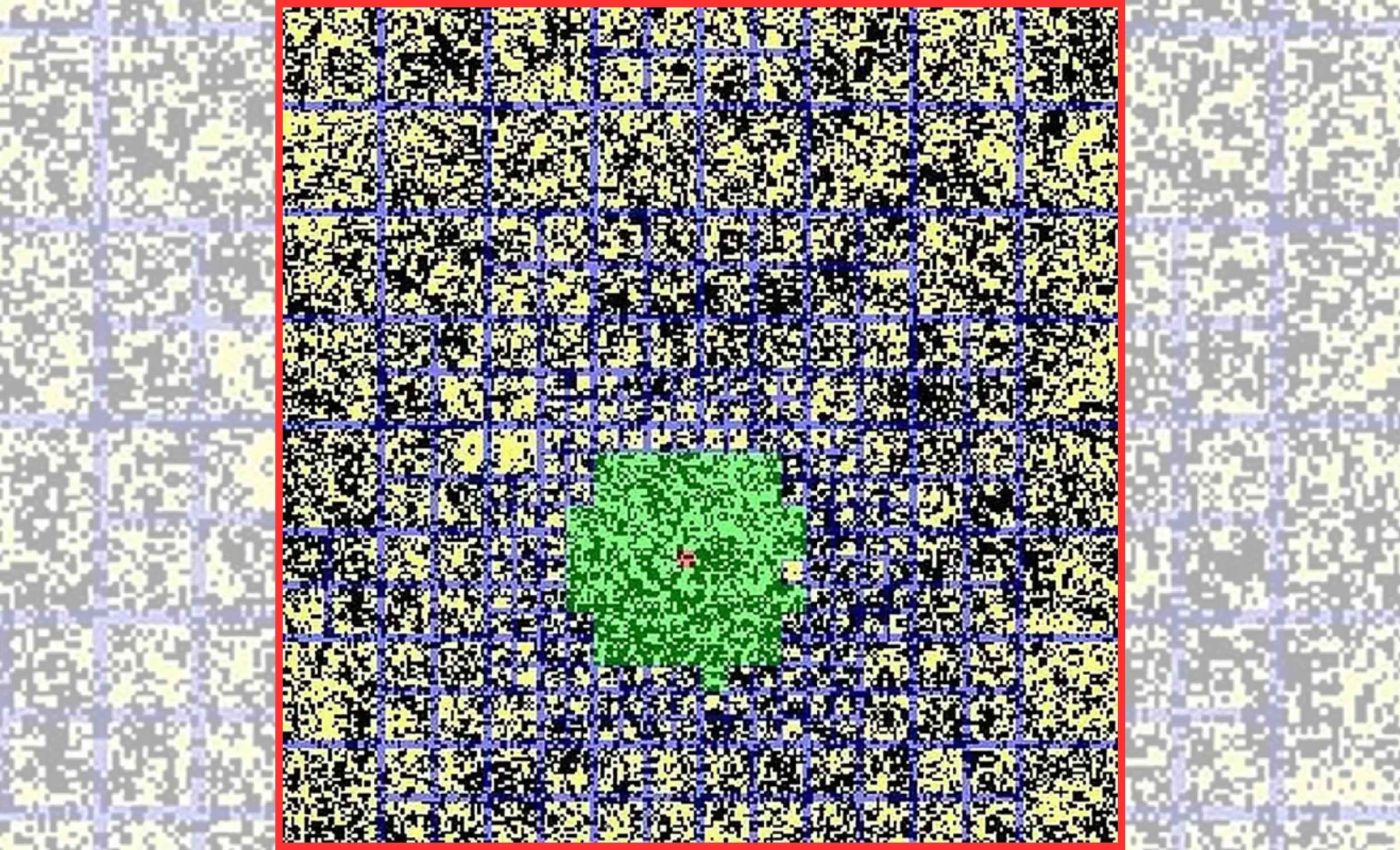

Much of the excitement comes from using the algorithm to study nonequilibrium processes, systems busy relaxing after a sudden change.

Physicists often quench a model, dropping its temperature abruptly, to see how order creeps in over time across the system.

These processes are increasingly becoming the focus of attention for statistical physicists worldwide.

That was how Wolfhard Janke, professor at Leipzig and senior author, described the field in the university’s announcement.

Long range models show rich behavior during a quench, with patterns of up spins and down spins coarsening into growing domains.

By making these simulations feasible at very large sizes, the new method lets researchers measure how those domains grow and age with unprecedented precision.

The same machinery also handles phase separation, the process where mixed components spontaneously split into distinct regions.

That covers problems from droplet formation on cold windows to mixtures inside living cells and industrial fluids.

Lessons from Monte Carlo simulations

Systems with long range forces show up across physics, from gravitating star clusters to plasmas and dipolar materials, and they often defy simple intuition.

A comprehensive review has highlighted how these interactions can even break textbook thermodynamic rules, leading to strange ensemble behavior and very slow relaxation.

For many open problems, simulation is the only realistic way to connect microscopic models with measurable quantities in the lab.

Making long range Monte Carlo practical lets theorists attack questions that were once left to rough approximations or highly simplified toy models.

At much smaller scales, nanoscale forces, long range electrodynamic and electrostatic interactions, govern how thin films, colloids, and soft materials stick and break.

Fast long range simulations give designers a new tool for testing how subtle changes in geometry or chemistry might tune those interactions.

Looking ahead, quantum simulators, controllable systems built from trapped ions or Rydberg atoms, already explore long range spin physics in the lab.

Efficient classical algorithms for long range models can guide and interpret those experiments, tightening the link between computation, theory, and quantum hardware.

The study is published in Physical Review X.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–