Scientists say there is 'no clear line' between human-made and natural disasters anymore

Disasters across the U.S. landscape are no longer rare events. Massive floods, raging wildfires, and extreme droughts – once expected every few centuries – are happening more often. And they’re getting worse.

These disasters aren’t just nature being wild. They’re more like nature on a short fuse, with humans often lighting the match.

Big changes in land damage

Since the early 1980s, the U.S. has seen big changes in how its land gets disturbed.

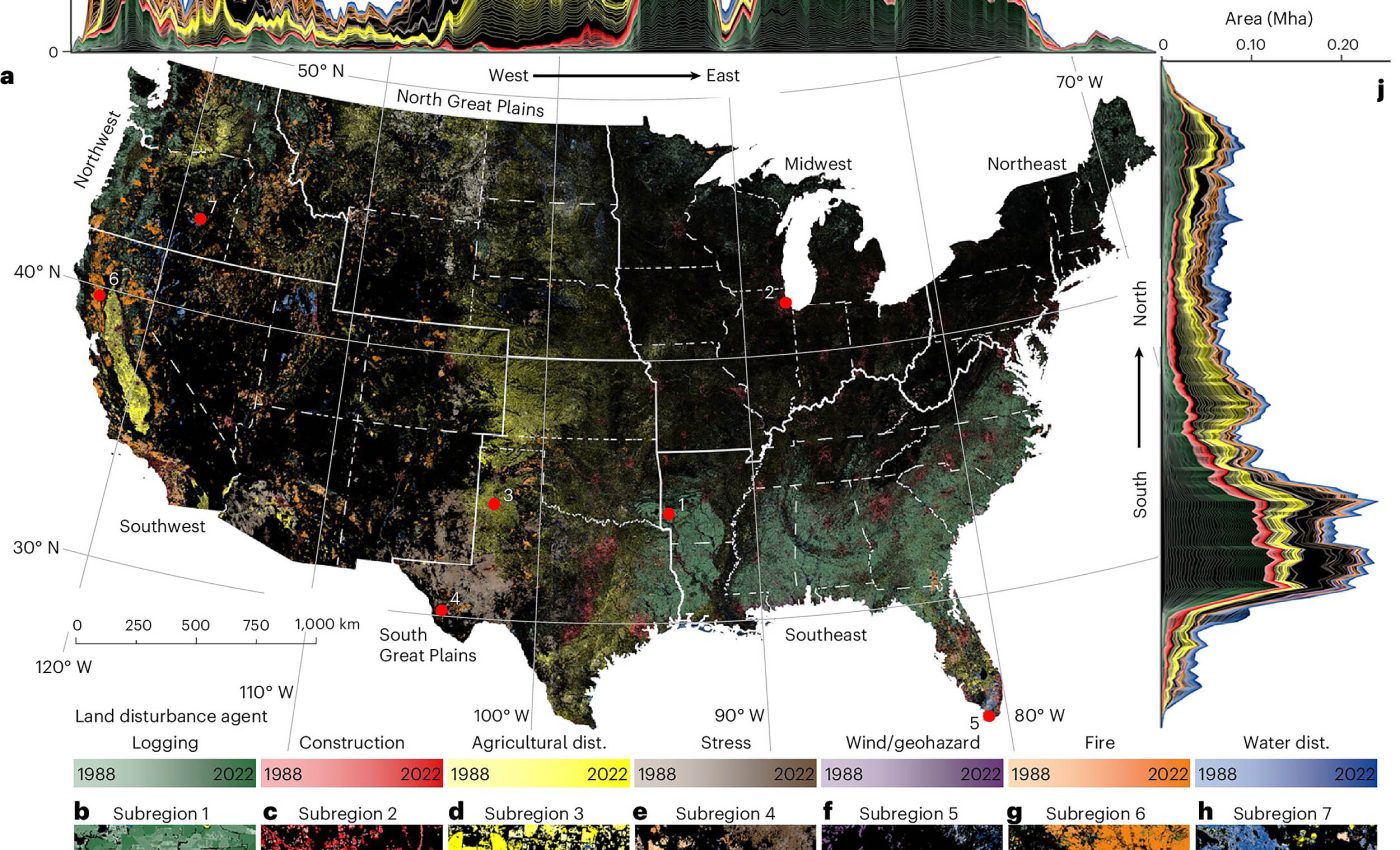

Scientists tracked these changes by digging into over 40 years of satellite data, studying when and where land was damaged – by fires, floods, construction, farming, and more.

These disturbances reshape forests, fields, cities, and coasts. They’re part of Earth’s natural rhythm. But now, there’s a shift. The types of events, as well as their causes, have changed dramatically.

Until recently, people thought of disasters like hurricanes and wildfires as purely natural. Lightning sparks a fire and heavy rainfall overflows a river – simple cause and effect. But that story is changing.

Not-so-natural disasters

Now, scientists say we’re living in a world where very few disasters are truly natural. The line between nature and human activity has gotten blurry.

Wildfires, for example, are not just ignited by lightning anymore. More often, they are caused by power lines, campfires, or sparks from equipment.

Even when nature strikes first, fires are worsened by human activities such as logging and building in fire-prone areas.

Researchers in the Global Environmental Remote Sensing Lab (GERSLAB) at the University of Connecticut spent nearly a decade developing a way to sort out the causes of these events across the entire United States.

“We feel we’re no longer able to call these disturbances ‘natural disturbances,’ so we made this new framework that has human-directed compared to ‘wild’ disturbances like vegetation stress, geohazard, wind, and fire that we put into another category because they are also greatly influenced indirectly by humans,” said Zhe Zhu, who led the project.

Tracking wild disturbances in the U.S.

The team analyzed Landsat satellite data going back to 1982, using an algorithm called COLD (Continuous Change Detection and Classification), to track how land was changing.

“For example, we can capture wild disturbances, like wildfires or hurricanes, and we can also capture human-directed disturbances, like logging, construction, and agriculture,” said Shi Qiu, one of the study’s authors.

“We used long-term Landsat satellite data to capture those disturbances in the past decades to see how those disturbances have shifted in the U.S.”

You can explore the dataset here.

Rise of wild disturbances

The results showed that human-directed disturbance is huge in the U.S., but has decreased in the past decades, noted Zhu. “Meanwhile, we found that wild disturbance is increasing. That is a major finding.”

This rise isn’t just about more fires or storms. It’s about how much land the disasters are damaging and how fast the phenomenon is increasing. Some events are now affecting larger areas and hitting harder than before.

“They are going wild and that is why we feel like ‘wild’ is quite useful for describing those disturbance agents,” explained Zhu.

Disasters are stacking up

There are signs of increasing wild disturbances everywhere. Flash floods in Texas killed over 100 people. Fires in California and Oregon have grown faster than firefighters can contain them.

Parts of the Northeast are seeing forests get chewed apart by years of drought and spongy moth infestations.

“They’re all linked together: changing our land is causing major disasters and landscape change at a scale we haven’t seen before,” said Zhu.

Even though some changes seem to happen overnight – like a sudden firestorm or a flash flood – this study shows the build-up has been long in the making. And the trends are not smooth or predictable.

According to Zhu, the disturbance patterns are not increasing in a straight line, which means it’s tricky to know how bad things might get. But we do know they’re getting worse.

Wild disasters beyond U.S. borders

The research team isn’t stopping here. They’re now exploring ways to use the same method in other regions of the world to see if the pattern holds.

“This is not simple research that one person or a few people can do. We have lots of collaborations with remote sensing experts at other universities and outstanding ecologists. All of us worked together to make this happen,” noted Qiu.

“To analyze this dataset, the UConn High-Performance Computing facility also gave us a lot of support.”

The research could help shape how we plan for future disasters – before they strike. Floods, fires, and droughts aren’t random acts of nature anymore.

They’re signals that something bigger is shifting. And we are not just witnesses – we’re part of the cause.

The full study was published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–