Titan's weather resembles Earth's, but runs on methane instead of water

Saturn’s moon Titan appears as a fuzzy, yellow ball from space, shrouded in dense clouds that conceal an interesting world beneath.

Though alien in appearance, the moon shares unexpected similarities with Earth. It has clouds, rain, and even lakes – but instead of water, Titan’s weather runs on methane.

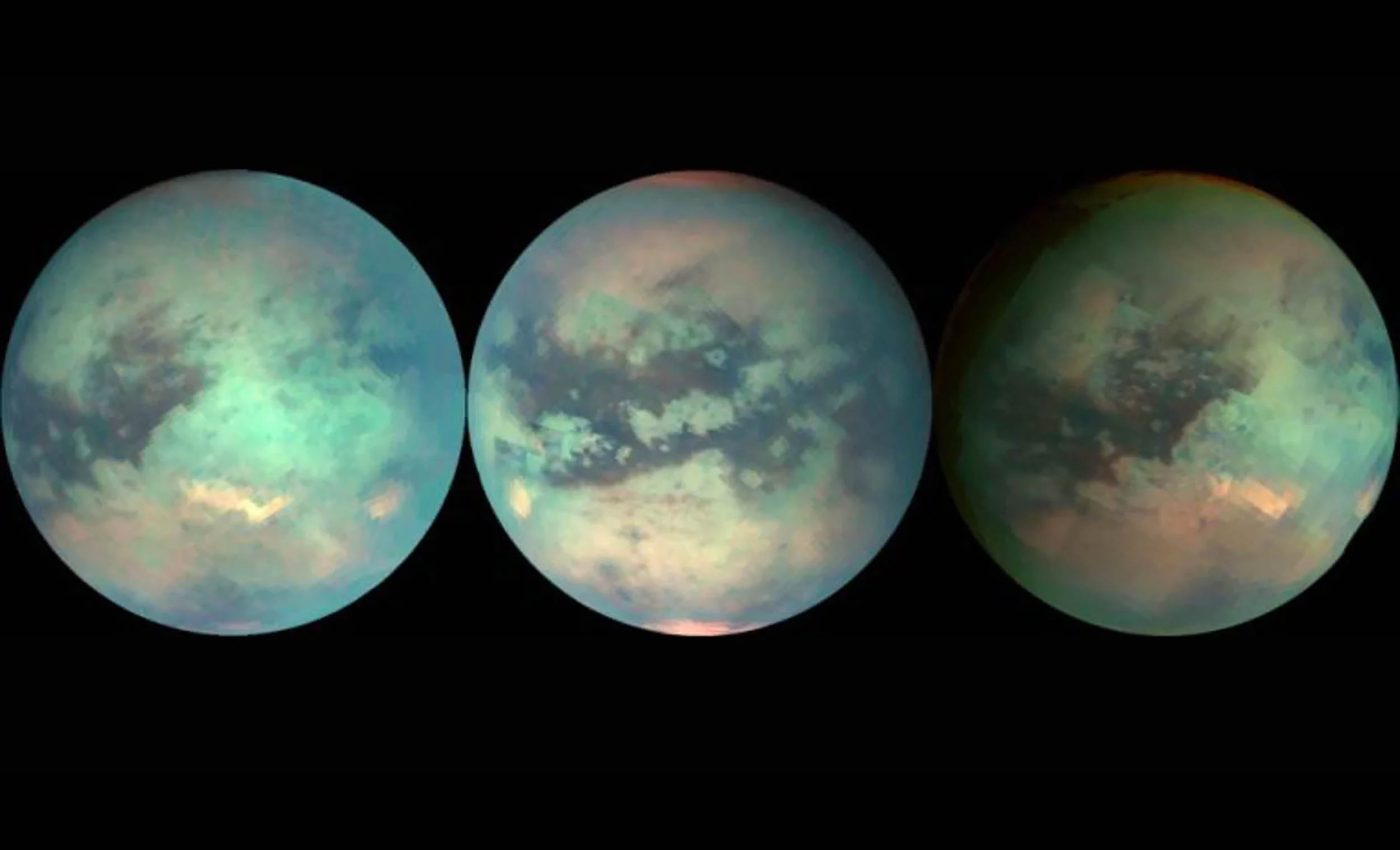

Thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope and the Keck II Telescope, scientists have now discovered evidence of methane clouds ascending in Titan’s northern hemisphere. These latest images also detected a rare carbon-based molecule aloft in Titan’s atmosphere.

Combined, these findings give us a better view of the weather on this moon, and its complex chemistry.

Summer clouds over Titan

Researchers from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and the W.M. Keck Observatory observed Titan in late 2022 and mid-2023.

The team saw methane clouds forming in the mid and upper parts of the moon’s northern hemisphere. This is Titan’s summer season, and most of its lakes and seas are concentrated in this region.

Methane on Titan works a lot like water does on Earth. It evaporates, rises through the atmosphere, condenses into clouds, and sometimes falls as rain.

But there’s one big difference: Titan’s surface is cold enough to freeze water solid. The rain that falls there is oily and bitterly cold, and it lands on a surface where water ice is as hard as rock.

“Titan is the only other place in our solar system that has weather like Earth, in the sense that it has clouds and rainfall onto a surface,” explained lead author Conor Nixon of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Tracking Titan’s rising clouds

The new images showed clouds moving upward over a period of days. This suggests that convection – the process of warm gases rising – is active in Titan’s northern hemisphere.

Until now, such motion had only been observed in the southern hemisphere.

Most of Titan’s lakes and seas are located in the north, covering an area roughly the size of the Great Lakes in North America. Scientists believe methane may be evaporating from these lakes, and fueling the clouds above.

On Earth, the troposphere – the lowest layer of the atmosphere – reaches about 7 miles (12 kilometers) high. On Titan, the same layer stretches up to around 27 miles (45 kilometers) because of the moon’s low gravity.

By using different infrared filters, Webb and Keck were able to peer into various layers of Titan’s sky. They tracked the altitude of the clouds but did not directly observe any rainfall.

Clues to life from Titan’s weather

Titan continues to draw interest from scientists because of its rich chemistry. It has many carbon-based molecules, which are essential to life. Understanding how these chemicals form on Titan may help explain how life began on Earth.

Methane (CH₄) is the starting point for most of this chemistry. When sunlight or charged particles hit the upper atmosphere, methane breaks apart.

The fragments then rearrange and form new compounds like ethane (C₂H₆) and other more complex carbon molecules.

Webb detects elusive molecule

One of the most exciting results from the Webb observations was the detection of a short-lived substance called the methyl radical (CH•3). It forms when methane molecules are split and it is very reactive.

Until now, scientists had seen the beginning and end products of chemical reactions on Titan, but not this middle step.

“For the first time, we can see the chemical cake while it’s rising in the oven, instead of just the starting ingredients of flour and sugar, and then the final, iced cake,” said co-author Stefanie Milam of the Goddard Space Flight Center.

This new observation allows researchers to study chemical reactions as they happen in Titan’s upper atmosphere.

Titan’s fate without methane

Titan’s chemistry may also give clues about its long-term future. When methane breaks apart, it doesn’t all turn into useful new molecules. Some of the hydrogen escapes into space.

Unless methane is somehow replenished from Titan’s crust or deep interior, it will eventually disappear.

Something similar happened to Mars. Water vapor broke apart, and the hydrogen drifted away. That process left behind a dry, dusty world.

“On Titan, methane is a consumable. It’s possible that it is being constantly resupplied and fizzing out of the crust and interior over billions of years,” said Nixon. “If not, eventually it will all be gone and Titan will become a mostly airless world of dust and dunes.”

Preparing for the Dragonfly mission

While Webb and Keck provide valuable views of Titan’s weather from afar, scientists are preparing for a closer look. NASA’s Dragonfly mission is scheduled to land on Titan in 2034. This flying drone will explore the surface, collecting samples and making direct measurements.

The Dragonfly mission will give scientists a close-up look at Titan’s surface and chemistry. Its discoveries will work hand-in-hand with Webb’s large-scale atmospheric data.

Heidi Hammel is vice president of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, and a Webb Interdisciplinary Scientist.

“By combining all of these resources, including Webb, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, and ground-based observatories, we maintain continuity between the former Cassini/Huygens mission to Saturn and the upcoming Dragonfly mission,” she explained.

Together, these tools are helping researchers uncover the secrets of Titan – one methane cloud at a time.

Click here to watch a NASA video analysis of rain clouds on Titan…

The full study was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–