Fossil discovery reveals two human ancestor species lived together 3.4 million years ago

When a small set of ancient foot bones turned up in Ethiopia years ago, the fossils raised more questions than answers.

The pieces were odd enough to stand out from anything scientists had seen from that time period. They looked old, even by human evolution standards, and they hinted at a way of walking that did not match the familiar pattern linked to early ancestors.

The bones sat in that curious space for a while, waiting for more evidence to make sense of them.

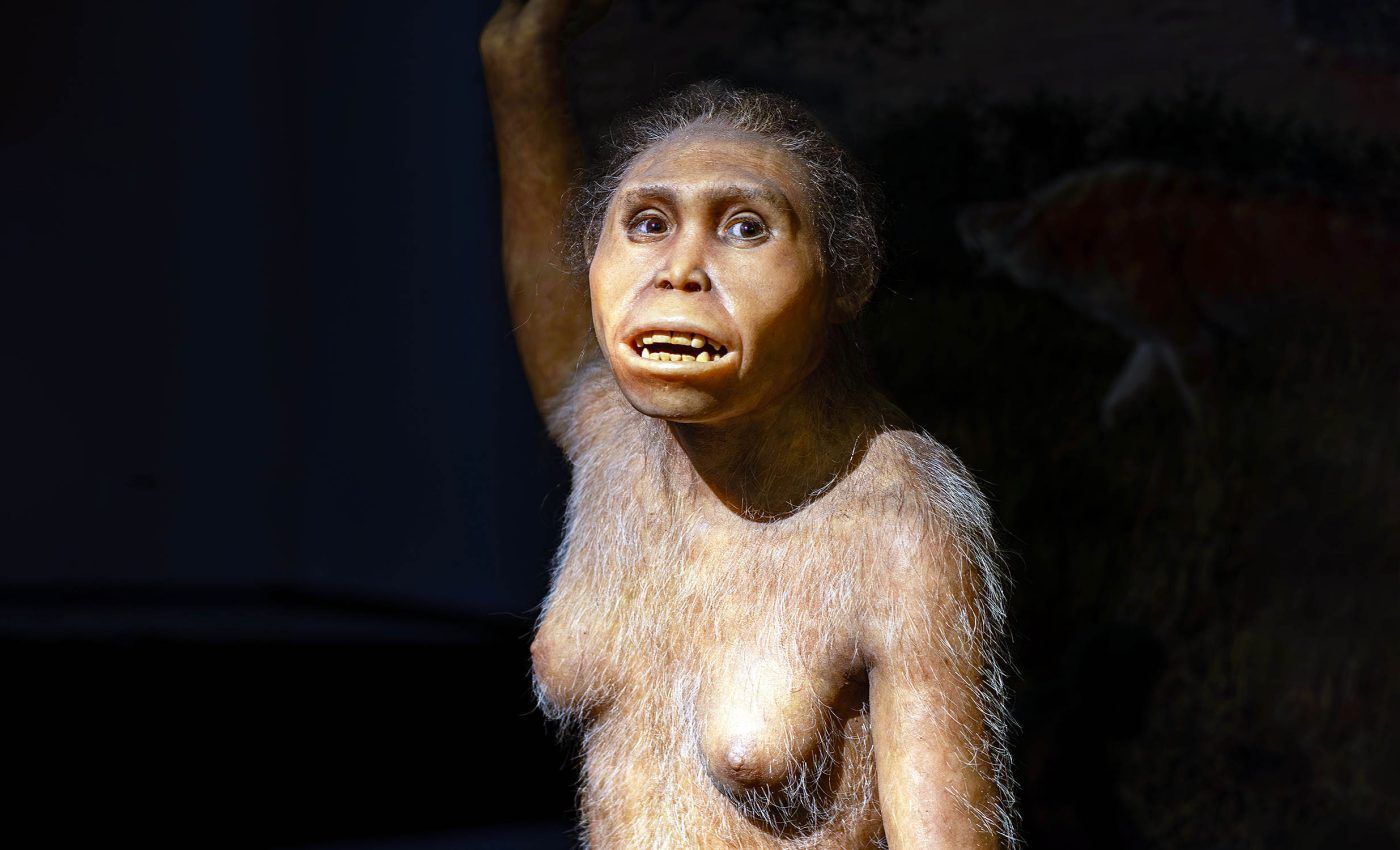

Those clues finally clicked into place. The foot, about 3.4 million years old, has now been matched to a species separate from the famous Australopithecus afarensis, best known from the fossil called Lucy.

This confirms that two different kinds of ancient hominins lived side by side in the same region.

Until now, scientists were not entirely sure how many species were sharing that landscape or how different their lifestyles really were.

A. deyiremeda and A. afarensis

The foot was first found in 2009 in the Afar Rift, buried in layers of ancient sediment. It included eight bones and was later nicknamed the Burtele Foot.

“When we found the foot in 2009 and announced it in 2012, we knew that it was different from Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, which is widely known from that time,” said Yohannes Haile-Selassie, a paleoanthropologist from Arizona State University.

He explained that naming a species from bones below the neck is rare. Scientists usually rely on skulls, jaws, or teeth because those features tend to show clearer differences.

Back then, a few teeth had turned up in the same area, but the team was not sure they matched the foot.

Years later, more fossils came to light. By 2015, researchers named a new species, Australopithecus deyiremeda, though the original foot was not included because the link still felt uncertain.

After a decade of steady work, new remains allowed the team to confidently connect the Burtele Foot to A. deyiremeda.

The Burtele Foot

The discovery matters because this site, Woranso-Mille, now provides direct evidence that two early hominin species lived at the same time in the same landscape.

The Burtele Foot turned out to be more primitive than Lucy’s. It had an opposable big toe that was helpful for climbing, while members of Lucy’s species had already shifted to a fully forward-pointing big toe for walking.

The way A. deyiremeda moved was different from ours as well. It walked on two legs but pushed off from its second toe instead of its big toe.

“The presence of an abducted big toe in Ardipithecus ramidus was a big surprise because, at 4.4 million-years-ago, there was still an early hominin ancestor which retained an opposable big toe, which was totally unexpected,” said Haile-Selassie.

“The whole idea of finding specimens like the Burtele foot tells you that there were many ways of walking on two legs when on the ground, there was not just one way until later,” he added.

A. deyiremeda teeth

Teeth often reveal clues about diet, and researchers used them to understand how A. deyiremeda fed itself. Naomi Levin sampled eight of the 25 teeth found at Burtele for isotope analysis.

“I sample the tooth with a dental drill and a very tiny (< 1mm) bit this equipment is the same kind that dentists use to work on your teeth,” said Levin.

She removed small amounts of enamel powder and studied the chemical signals preserved inside.

The results showed that A. deyiremeda relied mostly on C3 plants from trees and shrubs. Lucy’s species ate a mix of C3 resources and C4 plants such as tropical grasses.

“I was surprised that the carbon isotope signal was so clear and so similar to the carbon isotope data from the older hominins A. ramidus and Au. anamensis,” Levin said.

“I thought the distinctions between the diet of A. deyiremeda and A. afarensis would be harder to identify, but the isotope data show clearly that A. deyiremeda wasn’t accessing the same range of resources as A. afarensis, which is the earliest hominin shown to make use of C4 grass-based food resources.”

Tracing time and terrain

Understanding when and where these species lived required careful geological work.

Beverly Saylor explained that her team spent years sorting out how different layers of fossil-rich sediments connected across the site.

“We have done a tremendous amount of careful field work at Woranso-Mille to establish how different fossil layers relate, which is crucial to understanding when and in what settings the different species lived,” she said.

This helped confirm the age of the fossils and the environmental backdrop the species moved through.

Child from the same species

Among the discoveries at the site was a small jaw from a young A. deyiremeda individual. The jaw still held baby teeth, and deeper inside were adult teeth in various stages of development.

Gary Schwartz explained that CT scans allowed the team to estimate that the child was about 4.5 years old when it died.

“For a juvenile hominin of this age, we were able to see clear traces of a disconnect in growth between the front teeth (incisors) and the back chewing teeth (molars), much like is seen in living apes and in other early australopiths, like Lucy’s species,” said Schwartz.

He added that even with all the diversity seen in early hominins, their growth patterns were surprisingly similar.

Lessons from Australopithecus deyiremeda

Understanding how these ancient species lived, moved, and shared resources gives scientists a better sense of how early hominins managed to coexist without wiping each other out.

“All of our research to understand past ecosystems from millions of years ago is not just about curiosity or figuring out where we came from,” said Haile-Selassie. “It is our eagerness to learn about our present and the future as well.”

“If we don’t understand our past, we can’t fully understand the present or our future. What happened in the past, we see it happening today. In a lot of ways, the climate change that we see today has happened so many times during the times of Lucy and A. deyiremeda.”

According to Haile-Selassie, what we learn from that time could actually help us mitigate some of the worst outcomes of climate change today.

The story of the Burtele Foot shows how even a small set of bones can shift our understanding of human history.

The research also reminds us that evolution did not follow one clean path. It was a busy landscape filled with different species testing out different ways of living. Understanding that mix helps us see our own place in a much longer timeline.

The full study was published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–