UN warns the world is letting conservation projects fade away, reversing solid progress

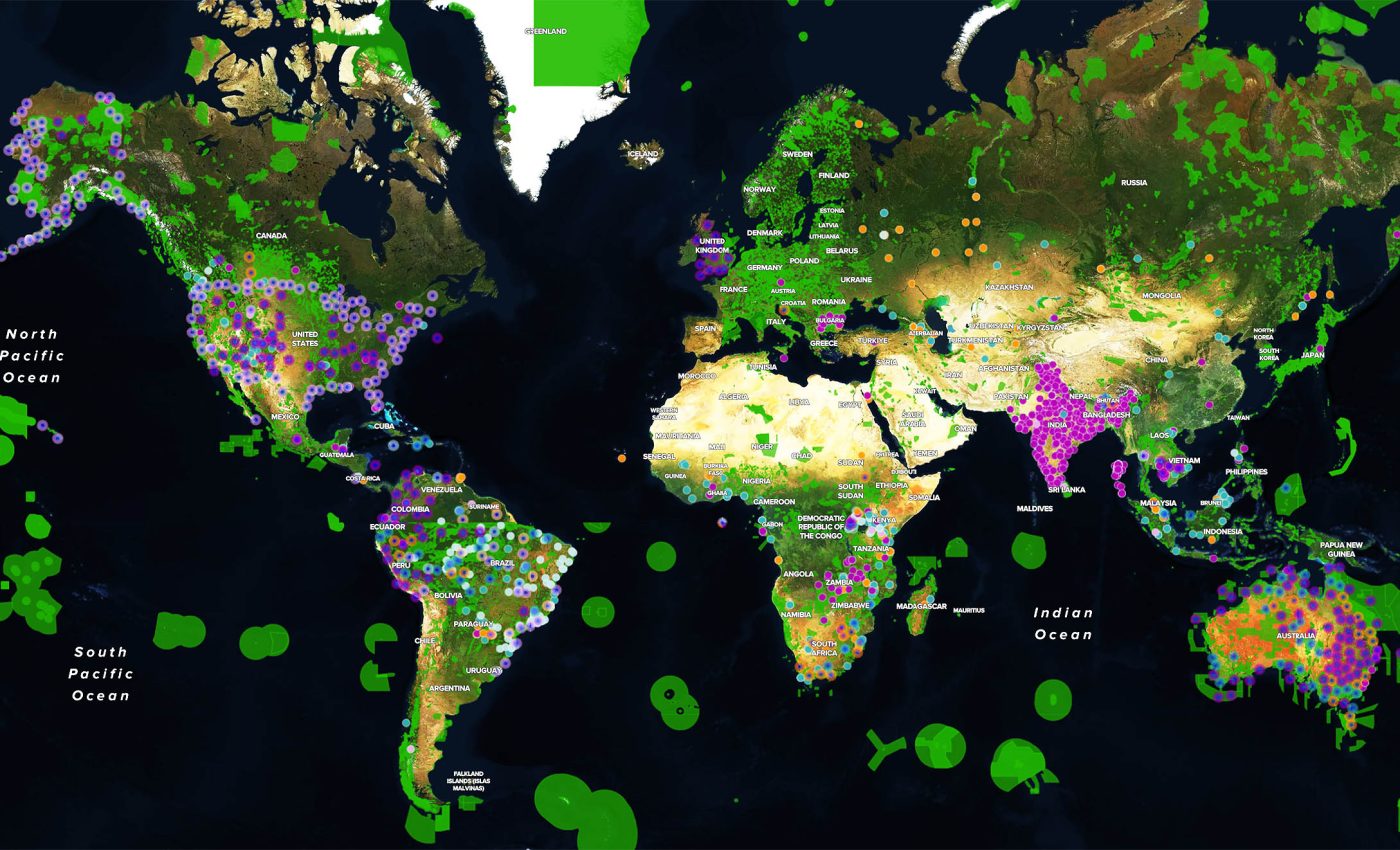

Around the world, conservation projects are quietly fading, and the losses are adding up. A new international study finds that nearly one in three efforts stalls or disappears within a few years.

This alarming issue is leaving ecosystems vulnerable and environmental progress overstated just as global leaders meet for COP30 in Brazil.

The problem isn’t just vanishing projects – it’s how success is counted. Many programs are celebrated when they launch but vanish from oversight once funding ends or protections weaken.

On paper, the world looks greener than it is. In reality, abandoned parks, neglected patrols, and rolled-back laws are erasing gains that once safeguarded species, habitats, and carbon stores.

When conservation stops counting

Here is how the authors define conservation abandonment – when commitments lapse or legal protections are rolled back, and on-the-ground work stops. It includes quiet neglect and formal reversals that erase earlier gains.

The work was led by Dr. Matthew Clark, a postdoctoral researcher, at the University of Sydney. His research focuses on how conservation programs persist over time.

Formal reversals are often recorded as Protected Area Downgrading, Downsizing and Degazettement (PADDD) – legal actions that weaken, shrink, or erase protected status. Abandonment also covers programs outside parks that simply stop operating.

These cases can sit unnoticed in official tallies that still count a park or project as active. The result is progress on paper that fails to protect species, habitats, or carbon stores.

Conservation projects fail without persistence

Ecological recovery usually takes decades, so short-lived projects rarely secure lasting results. “Paper parks,” places protected on paper but unmanaged in practice, do little to stem habitat loss.

“Evidence suggests at least one-third are abandoned just a few years after implementation,” said Dr. Clark. That kind of churn scrambles budgets, weakens trust, and resets hard-won local partnerships.

Short funding cycles tempt teams to prioritize ribbon-cuttings over maintenance. Real durability comes from steady governance, reliable financing, and local buy-in built over time of conservation projects.

When pressures rise, PADDD can follow, as legal protections become targets for rollback. Abandonment can also emerge quietly when managers shift staff, vehicles break, or monitoring stops.

The numbers behind the warning

A 2019 study tallied 3,749 PADDD events enacted across 73 countries between 1892 and 2018. Those changes stripped or relaxed protections across an area comparable to a large country.

Under the Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity framework, nations pledged to conserve at least 30 percent of land and sea by 2030. Hitting that target demands not just new lines on maps but proven staying power.

In Canada, a marine refuge classified as an “other effective area-based conservation measure” – areas outside standard parks that still deliver conservation outcomes – later permitted exploratory oil drilling across about 10,200 square miles (26,400 square kilometers). That shift is documented in a 2024 One Earth analysis focused on reporting quality.

Australia illustrates another pressure point, with about 386,000 square miles (1 million square kilometers) of its marine estate rezoned in 2018 to allow more extractive use. That scale is summarized in an Australian Parliamentary Library brief.

When protection lapses, nature pays

Local enforcement is often the first thing to go when funding ends. Poaching, illegal logging, and unregulated fishing can return within a season locally.

Monitoring stops next, so managers lose early warnings on invasive species or bleaching. Without data, midcourse fixes never happen, and small problems grow.

Communities feel the difference when promised jobs or revenue fail to materialize. That disappointment can sour attitudes toward future conservation offers that might actually work.

Carbon projects carry their own risks if permanence fails. Once protections lapse, stored forest carbon can leak back into the air, and accounting unravels.

Persistence over conservation promises

Lasting protection needs more than good intentions – it needs proof. Conservation should be judged not by how many projects start, but by how many endure.

Track whether protections persist, not just whether they begin. A clear persistence rate – the percentage of projects still active five or ten years later – would shift incentives overnight.

Measure the share of sites with active patrols, working equipment, and up-to-date management plans. Post independent audits online so communities can see whether commitments are kept.

Finance should have its own durability test. Report years of effective management per dollar spent to show which programs deliver long-term results. Reward teams that keep outcomes alive through droughts, storms, and market shocks.

Turning promises into permanence

Policies only matter when they last on the ground. Real conservation depends on keeping promises active long after the headlines fade. That means turning accountability from an afterthought into a requirement.

Governments should create national registers that log every PADDD proposal, rollback, and reinstatement. Communities should also have a simple way to flag when on-the-ground management has stopped.

Area gains should not count toward national targets unless they come with matching budgets, staff, and equipment. Annual progress reports must include verified persistence figures, not just acreage and announcements.

Finally, link trade and procurement rules to strong conservation performance so companies share responsibility for keeping protections alive. When benefits reach households near parks, support for rules stays higher and conflicts cool off.

How to fix the blind spot

First, the world needs a routine check on whether protections still function years after launch. Global databases record coverage, but effectiveness is assessed in only about 11 percent of listed sites, as noted in the Protected Planet 2020 report.

Second, design conservation projects to last by aligning benefits with local priorities and stable funding. That can mean trust funds, enforceable easements, or rules that cannot be easily watered down in the next budget.

Build permanence into contracts so responsibilities remain clear even when staff change. Link funding tranches to verified milestones so maintenance, enforcement, and monitoring do not slip or stall.

Plan for climate and land use shocks that can derail management. Flexible rules that communities help shape are more likely to survive bad years and political swings than one size fits all mandates.

The study is published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–