Underground fungi networks that sustain all life on Earth are in danger

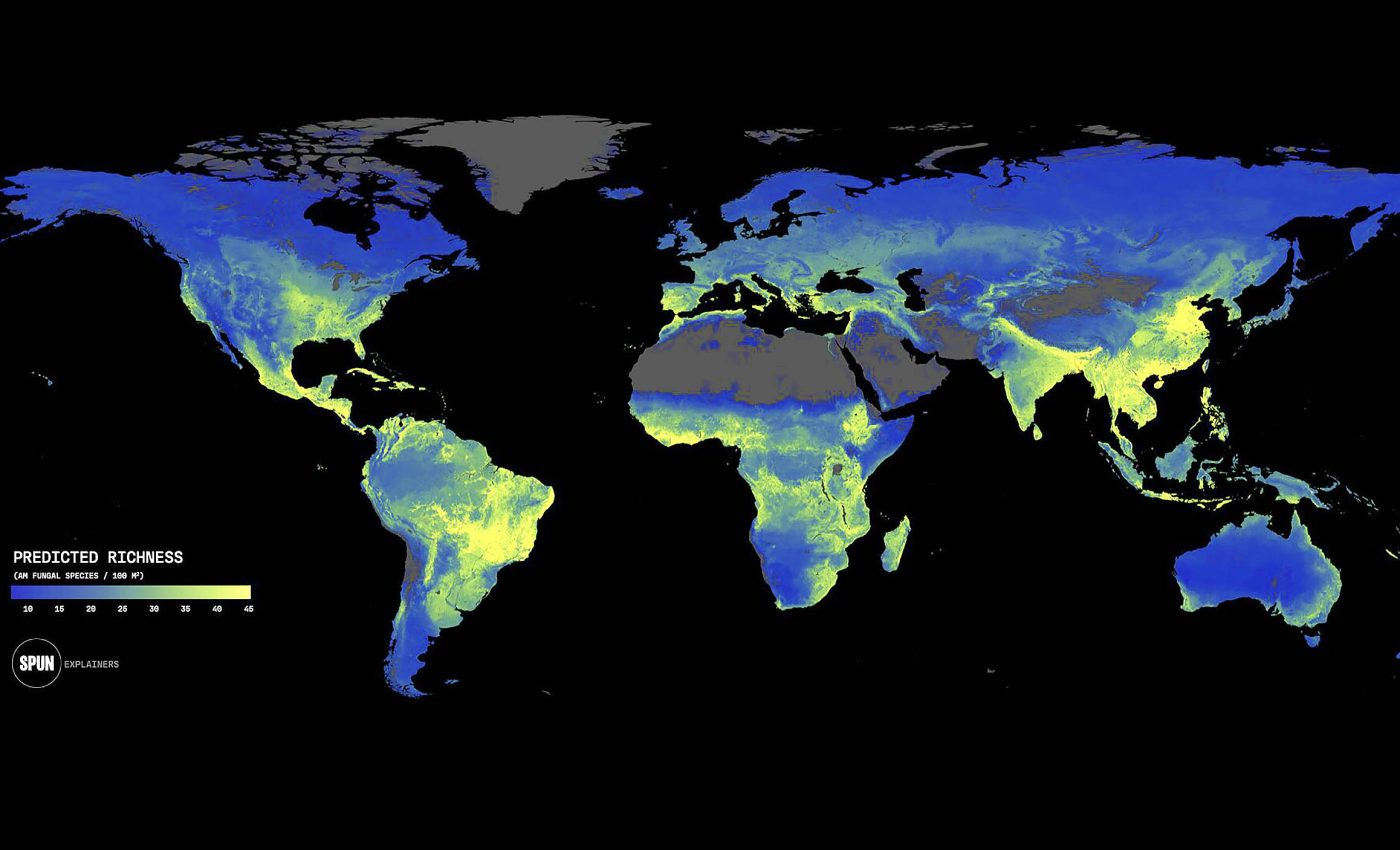

With over 2.8 billion fungal DNA sequences from 130 countries, scientists have produced the first high-resolution global maps of underground mycorrhizal fungi. These fungi support ecosystems by transporting nutrients, capturing carbon, and protecting plant health.

Yet, over 90 percent of this underground biodiversity lies outside protected areas. That makes these vital ecosystems vulnerable to environmental damage.

The data powers a new interactive platform called the Underground Atlas. This tool helps anyone explore fungal biodiversity from Ethiopia to Brazil, and from Tasmania to West Africa.

These maps expose not only diversity but also rarity, revealing patterns previously hidden from view.

Why underground fungi matter

Mycorrhizal fungi form massive underground networks that interact with nearly every plant.

These fungal systems capture more than 13 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year – about a third of global fossil fuel emissions. They help crops grow, rebuild forests, and regulate water cycles.

Still, fungi remain missing from major conservation plans. That absence is dangerous. When these networks get disturbed, forests regenerate more slowly, crops suffer, and entire ecosystems unravel.

“For centuries, we’ve mapped mountains, forests, and oceans. But these fungi have remained in the dark,” said Dr. Toby Kiers of Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN).

“They cycle nutrients, store carbon, support plant health, and make soil. When we disrupt these critical ecosystem engineers, forest regeneration slows, crops fail, and biodiversity aboveground begins to unravel.”

“This is the first time we’re able to visualize these biodiversity patterns – and it’s clear we are failing to protect underground ecosystems.”

Maps show fungi need protection

The research team used machine learning to build predictive maps from their vast dataset. These maps reveal fungal richness and rarity at a global scale, down to one square kilometer.

Less than 10 percent of biodiversity hotspots appear in protected areas, exposing a huge gap in global conservation strategy.

This work is the first large-scale scientific product of SPUN. The group launched in 2021 with the goal to map and protect Earth’s fungal networks.

“For too long, we’ve overlooked mycorrhizal fungi. These maps help alleviate our fungus blindness,” explained Dr. Merlin Sheldrake of SPUN.

A tool to explore underground fungi

Now, SPUN offers a powerful new tool: the Underground Atlas. It allows researchers, policymakers, and conservationists to explore biodiversity anywhere on Earth.

“The idea is to ensure underground biodiversity becomes as fundamental to environmental decision-making as satellite imagery,” noted Jason Cremerius of SPUN.

Users can locate biodiversity hotspots, identify rare fungal species, and support restoration work. The tool can inform the placement of conservation areas, especially in biodiversity-rich regions that remain unprotected.

“These high-resolution maps provide quantitative targets for restoration managers,” said Dr. Alex Wegmann from The Nature Conservancy. “Restoration practices have been dangerously incomplete because the focus has historically been on life aboveground.”

No legal shield for fungi

According to the researchers, the data could help shape climate and biodiversity laws. For example, Ghana’s coast hosts a vital underground fungal hotspot – yet this coast erodes by two meters each year. If left unprotected, this fungal diversity could vanish into the sea.

“Underground fungal systems have been largely invisible in law and policy,” said César Rodriguez-Garavito of NYU. “These data are incredibly important in strengthening law and policy across all of Earth’s underground ecosystems.”

SPUN has built a global dataset of 40,000 samples covering 95,000 fungal taxa. The organization partners with more than 400 scientists and 96 “Underground Explorers” from 79 countries. These teams now sample remote regions – from Bhutan and Mongolia to Ukraine.

Future depends on these networks

Despite the achievements, scientists have sampled just 0.001% of Earth’s surface. SPUN needs more data to improve maps, define restoration goals, and identify endangered fungal communities.

“These maps reveal what we stand to lose if we fail to protect the underground,” said Dr. Kiers.

To protect Earth’s underground biodiversity, collective action is essential. Researchers can partner with SPUN to expand data collection and improve the accuracy of fungal diversity maps.

Conservationists should use these insights to design strategic interventions and prioritize high-value ecosystems. Policymakers need to recognize the critical role of underground fungi by including them in biodiversity and climate frameworks.

The public can explore the Underground Atlas to better understand this hidden world and support ongoing efforts. Funders play a key role by investing in the next phase of global fungal exploration and restoration.

To see the hidden world beneath your feet, visit the Underground Atlas and help protect the life that sustains ours.

The study is published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–