Unique fish species reappears after vanishing for two decades

For the first time in more than 20 years, scientists have laid eyes on Moema claudiae, a tiny seasonal killifish from Bolivia that many feared had slipped into extinction.

The killifish was found in a rain-filled pond tucked inside a sliver of forest surrounded by farms. It’s a feel-good twist with a sobering edge: this species is hanging on, but just barely.

Killifish found after decades

Moema claudiae hadn’t been seen at its original site for decades; that place is now cropland. After years of surveying with no luck, the fish was listed as Critically Endangered and considered possibly extinct.

Then, researchers Heinz Arno Drawert and Thomas Otto Litz struck gold. They discovered a living population of killifish in a small, temporary pond in a remnant forest patch.

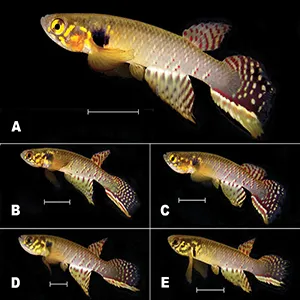

The paper documenting the finding includes the first live photographs, behavior notes, and natural history details ever recorded for the species.

“For me, it is something special to have rediscovered Moema claudiae,” Litz said. “This has shown that we now have the opportunity to preserve this species in the wild.”

“I am all the more pleased because Professor Wilson Costa named this species after his wife Claudia, and I would like to take this opportunity to thank him especially for decades of collaboration and support.”

One pond, several killifish

Seasonal killifish are specialists. They sprint through life in ephemeral pools during the rains. They lay drought-resistant eggs in the mud, then vanish as the ponds dry, only to reappear with the next downpour.

That strategy works until humans simplify the landscape and drain, plow, or pollute the small basins that cradle their eggs.

Here’s what makes this rediscovery jaw-dropping: that same pond shelters six other seasonal killifish species.

Scientists have documented the most genetically diverse seasonal killifish assemblage anywhere.

The location sits where Amazon forest meets the Llanos de Moxos savannas, a natural mash-up that seems to supercharge diversity.

Moema claudiae is threatened

Bolivia has lost nearly 10 million hectares of forest in the past 25 years. In the lowlands, deforestation and agricultural expansion are chewing up the very micro-wetlands these fishes depend on.

When you straighten watercourses, clear edges, and compact soils, those fleeting ponds either don’t form or they don’t last long enough for a life cycle to complete.

“Without rapid and effective action to curb the irrational expansion of the agricultural frontier in Bolivia’s lowlands, we risk losing some of the world’s most important terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems,” said Drawert, an expert at the Noel Kempff Mercado Natural History Museum.

“We cannot hope to achieve true social and economic well-being unless we also maintain the functionality of the ecosystems that sustain it.”

Keeping the species alive

Saving killifish isn’t about fencing one puddle. It’s about keeping a network of seasonal pools alive across a working landscape.

Practically, that means buffering and leaving vegetation around depressions. It also means routing farm machinery and chemical use away from wet spots in the rainy season and maintaining tree lines and swales that slow water so ponds can form and persist.

Basic mapping is needed to locate nearby pools, figure out which ones connect hydrologically, and prioritize the set that keeps the metapopulation breathing.

On the policy side, these ephemeral wetlands need to count in land-use decisions. They help recharge groundwater, support insect and amphibian booms that feed birds and bats, and, yes, keep these one-season wonders in the game.

Lessons from Moema claudiae

Seasonal killifish are little neon flags that a landscape still pulses the way it should. Lose them, and you’re usually losing the flood–drought rhythm that powers a whole web of life.

They’re also evolutionary originals – many are hyper-local endemics. Erasing a single population can erase an entire lineage’s future.

The rediscovery of Moema claudiae is exactly the kind of plot twist conservationists live for: a species written off as gone turns up alive, in time to matter. But it’s also a countdown.

This is the only known wild population. One dry year, one bulldozer pass, one “just this once” herbicide spray too close to the pond, and the story ends.

The path forward is doable, though. Protect the site and its catchment now, work with the surrounding landowners, and fan out to find sister ponds while there’s still a rainy season to reveal them. If those pieces come together, “possibly extinct” can turn into a genuine comeback.

The research is published in the journal Nature Conservation.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–