Unprecedented collapse: Panama's ocean upwelling fails for the first time in 40 years

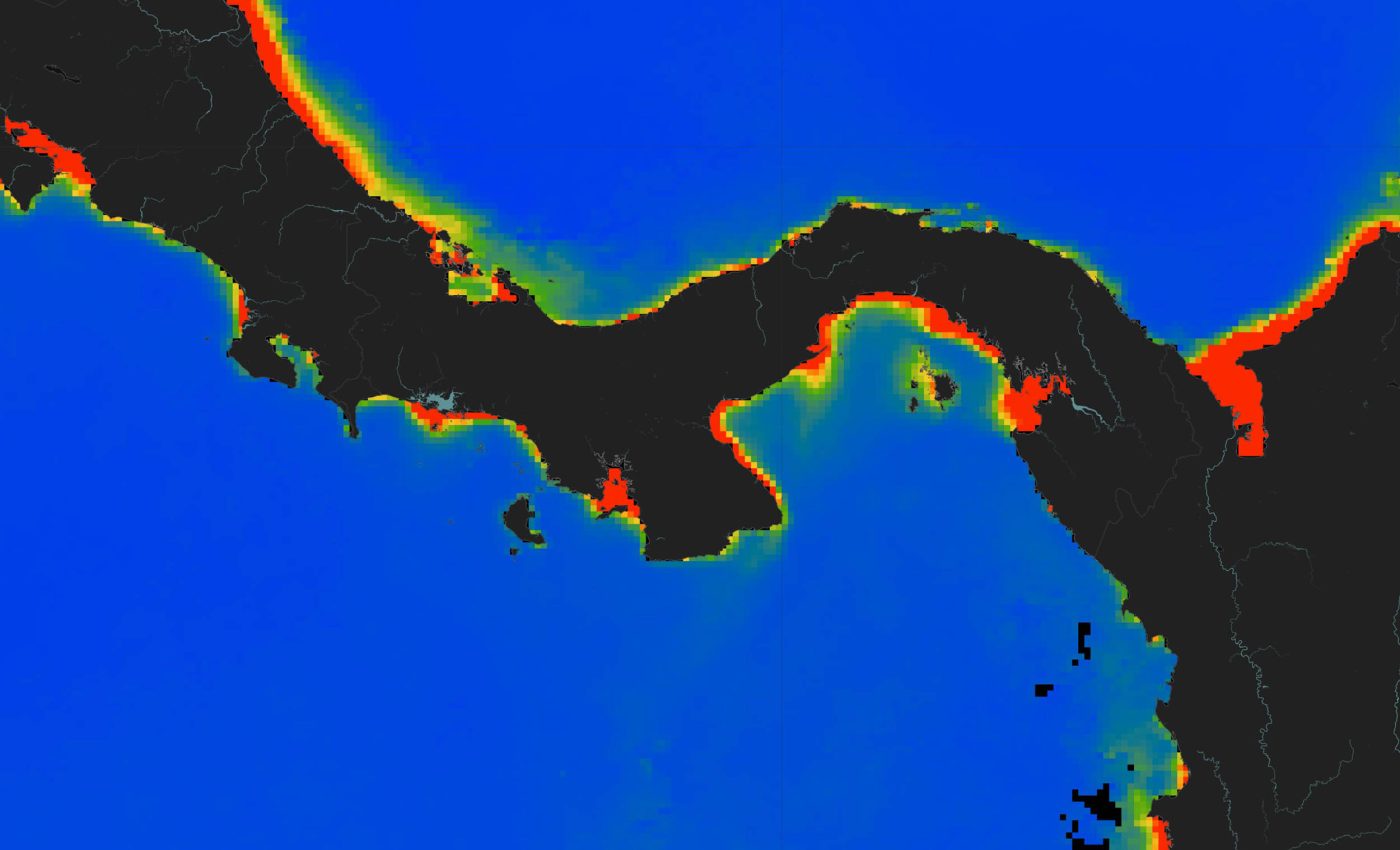

In early 2025, something unusual happened in the Gulf of Panama. The deep, cold water that normally rises to the surface each dry season never appeared. According to a new study, this seasonal upwelling failed for the first time in at least four decades.

Researchers recorded warmer surface waters, fewer cool days, and a steep decline in productivity during the months when the system is usually most active.

Lead author Aaron O’Dea of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) points out the event disrupted one of the Gulf’s most reliable ocean patterns.

His team’s data show that the region’s cool season shifted in ways that carry real consequences for both marine ecosystems and the people who depend on them.

Upwelling shapes ecosystems

Upwelling occurs when winds push surface water aside and allow deeper, nutrient-rich water to rise. That nutrient pulse fuels phytoplankton – tiny plant-like drifters that are the base of marine food webs.

The result is a burst of life that supports fisheries and cools nearshore waters. That cooling can reduce coral bleaching, the stress response when corals lose their symbiotic algae under heat.

A long term study of Panama’s Pacific shelf showed how predictable winter winds typically drive this cycle. Year after year, that reliability shaped coastal economies and expectations.

Waters stay warmer longer

The 2025 season broke the pattern in clear ways. Historically, Panama’s upwelling began by January 20, lasted about 66 days, and surface temperatures sometimes dipped to 66.2°F, with extremes near 58.8°F.

In 2025, surface temperatures did not fall below the 77°F threshold until March 4 – 42 days later than usual. The cool period persisted for only 12 days, an 82 percent reduction, and the minimum temperature was about 73.9°F.

The wind signal tells a similar story. When northerly winds did blow, their speeds and wind stress matched normal years, but they occurred 74 percent less often and relaxed 25 percent more hours than usual.

Those metrics line up with reduced biological production during the same window. Fewer cold days meant fewer nutrient injections and fewer phytoplankton-fueled food chains.

Weaker jets, weaker waters

To understand the physics, it helps to define the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ).

This is a band near the equator where trade winds meet and storms form, and its seasonal shift steers wind patterns across Central America.

In boreal winter, pressure gradients funnel air through mountain gaps to form the Panama Low-Level Jet (PLLJ).

The jet accelerates offshore winds that normally push surface waters away from the coast and set up the classic upwelling response.

The team notes that 2025 featured fewer of those northerly wind events. Fewer bursts meant less cumulative push on the ocean surface, so deeper water did not break the stratified layers and rise.

This change likely interacted with La Niña, a climate phase that can nudge the ITCZ north or south and modulate wind frequency. The authors flag this as a plausible driver but stop short of declaring a single cause.

Fisheries and reefs on the line

Upwelling hotspots punch above their size. They produce food and jobs by feeding forage fish that in turn support larger species targeted by coastal fleets.

Warm, stable surface layers can dampen that productivity. Less nutrient delivery means weaker plankton blooms and a thinner energy pipeline to the fish that communities depend on.

Reefs feel these swings too. During the 2015 – 2016 El Niño, evidence showed that upwelling in the Gulf of Panama moderated heat and reduced bleaching while nearby areas baked.

The two Pacific gulfs of Panama often move in opposite directions. A 2023 review described how the upwelling Gulf of Panama tends to run cooler and more nutrient-rich than the Gulf of Chiriquí, shaping different coral growth trajectories under today’s warming.

40-year record broken

The 40-year record makes the 2025 failure stand out. Average historical onset around January 20 contrasts with a March 4 threshold crossing in 2025.

The cool season shrank from roughly nine weeks to less than two weeks. Minimum sea surface temperature (SST) rose from historical lows near 66.2°F to about 73.9°F.

Northerly wind frequency fell by roughly three-quarters compared with typical seasons. Relaxation periods, when winds slacken and the ocean restratifies, increased by about one-quarter.

Those numbers capture a system that did not get enough wind energy often enough to do its usual work. The headline is not that winds were weak when they blew, but that they did not blow often.

What comes after collapse

Three questions now sit at the center of this story: Will the PLLJ return to its usual rhythm next dry season, will it keep sputtering, or will it swing between extremes that complicate planning?

If the failure of Panama’s upwelling repeats, fishers may need to adjust timing, gear choices, or target species for leaner seasons.

Reef managers may need localized alerts that treat upwelling corridors as temporary refuges that can fade without notice.

Models and moored sensors can close the gap. That means better wind tracking, finer SST mapping, and clearer links between physics, plankton, fish, and reefs across the Gulf.

The study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–