Unpublished images show that the Moon 'broke apart' billions of years ago

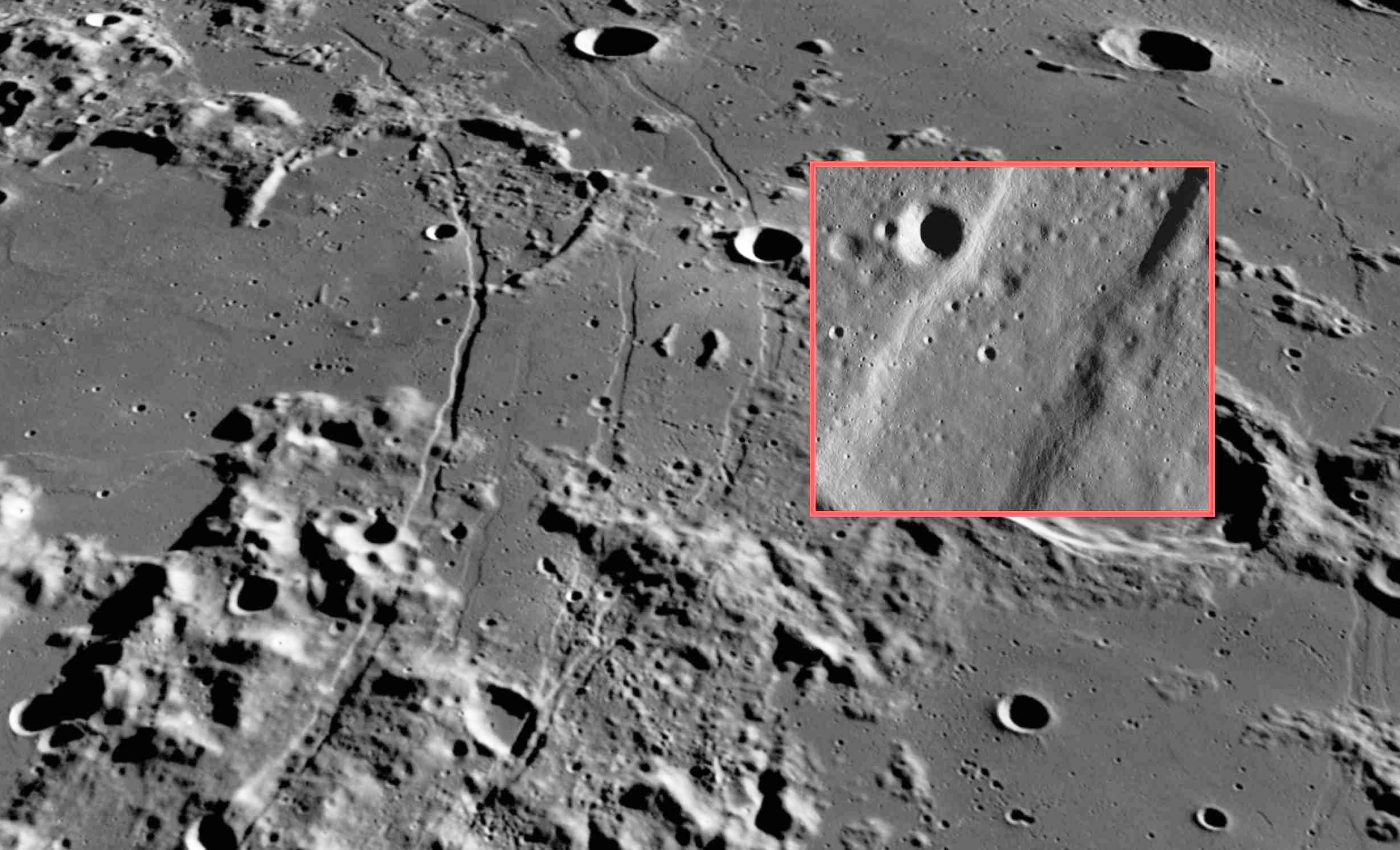

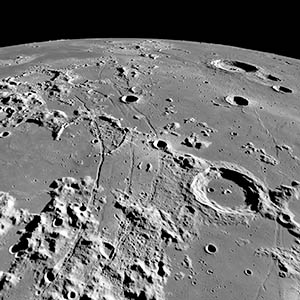

New oblique images from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) reveal enormous cracks, called grabens, curling around an ancient lunar sea on the Moon’s near-side.

These grabens are part of a broken ring that records how a huge patch of the Moon’s crust was pulled apart rather than squeezed together.

How a lunar sea grew too heavy

The work was led by Thomas Watters, a planetary scientist at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum (SNASM). His research focuses on how tectonic scars on airless worlds track the slow stretching and squeezing of their crust.

Near the Moon’s southwest, a circular basin named Mare Humorum is filled with dark basalt, dense volcanic rock that cooled from wide-spreading lava flows, which piles up into a heavy load on the crust.

Spacecraft tracking and impact studies show that this basalt layer is more than 2 miles thick near the basin’s center, making Humorum one of the Moon’s best natural stress tests.

Under that weight, the basin floor slowly sagged downward and inward. When the lava cooled and contracted, the stress spread outward and tugged at the stronger rocks around the edge of the basin.

During the Imbrian period, a long early chapter of intense lunar impacts and volcanism, eruptions fed Humorum with fresh lava for hundreds of millions of years.

As that lava pond settled, the rock ring around the basin fractured in a pattern that later imaging would reveal as a chain of graceful but deep valleys.

Understanding the moon’s grabens

Grabens are long valleys that form on the Moon when a block of crust drops between two normal faults as the surface stretches.

A recent detailed analysis shows that lunar grabens are the largest tensional linear structures on the Moon and that they cluster along the margins of mare basins.

A dedicated mapping campaign using global images from Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) identified more than 1800 separate graben segments on the Moon’s nearside alone.

Many of these troughs run for hundreds of kilometers while remaining only a few miles wide, which makes them narrow but powerful markers of ancient stress.

The same analysis of their ages finds that most large grabens formed between about 3.7 and 3.4 billion years ago, with activity peaking near 3.6 billion years ago.

When all of those valleys opened, the Moon’s radius grew by roughly 400 feet, a tiny change compared with its total size but a clear sign of global extension.

Later, smaller examples added another twist to the story. A high-resolution lunar graben was reported that likely formed less than 50 million years ago, showing that the Moon’s crust did not stop adjusting in deep time.

Broken ring around Mare Humorum

Along the eastern shore of Mare Humorum lies the Rimae Hippalus system, three main valleys that curve in a loose arc around the basin’s rim.

Together they trace a broken ring more than 150 miles long, with each valley marking a slightly different stage in how the crust responded to the sinking lava sea.

The innermost valley shows sharp walls and a clear drop between its floor and the surrounding terrain, which signals relatively little later disturbance.

Farther out, the grabens become shallower and less crisp, evidence that later lava seeped in and partly refilled the earlier fractures.

Fresh oblique views from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera line up the three main valleys in a single perspective, rather than slicing across them in overhead strips.

That angle highlights subtle changes in width, depth, and relief along each segment, allowing researchers to sort which pieces dropped first and which slumped later as the basin kept relaxing.

Grabens and Moon shrinking

“We think the moon is in a general state of global contraction because of the cooling of a still hot interior,” said Watters. He noted that this slow inward motion shapes many of the small faults seen across the lunar surface.

At the same time, the valleys show that this slow squeeze is not the whole story. The graben indicates that forces shrinking the Moon were overcome in some regions by forces pulling it apart, and that the contraction must be limited or the smaller valleys would not have formed.

Those young trenches sit on top of older structures like the Rimae Hippalus ring, proving that extension did not stop after the great early volcanic episodes.

Taken together, the global contraction and local extension paint a complex picture. The Moon as a whole is slowly cooling and shrinking, yet in certain places the crust is still opening along old weak zones, echoing stresses first set up when basins such as Humorum were loaded with lava.

Analyzing a frozen scar map

To order these events, lunar geologists rely on crosscutting relationships, the rule that any feature that slices another must be younger than what it cuts.

If a graben slices through a crater rim or a wrinkle ridge but not the other way around, the valley clearly opens after those earlier structures formed.

Around Mare Humorum, Rimae Hippalus intersects buried crater rims, subtle ridges, and younger impact scars.

By tracing each intersection, researchers build a timeline that runs from the initial basin-forming impact, through lava flooding and subsidence, to the final stages of fracturing and partial lava infill.

This timeline shows that the basin’s broken ring mainly dates to the Moon’s early volcanic era, even though a few smaller fractures nearby continued to open much later.

The result is a layered record in which every valley, ridge, and crater preserves one move in a long sequence of pushes and pulls.

Lessons from Moon grabens

Understanding where the lunar crust has stretched and sunk helps mission planners pick safe landing and construction sites.

Regions laced with sharp, fresh grabens may host loose blocks, hidden slopes, or lingering tectonic stress that future surface crews will want to measure carefully.

Mapping these fractures also helps scientists decide where to place new seismometers and deep drills.

Sites that cut across old weak zones, such as the margins of Mare Humorum, can reveal how thick the crust is and how far fractures reach beneath the surface.

Future orbiters and landers will keep filling in that stress map, linking ancient structures like Rimae Hippalus to the surprisingly young grabens now known across the nearside.

By reading those scars together, researchers continue to refine how and when the Moon’s surface first broke apart and how it is still changing today.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–