Scientists release open-source device that will help all humans communicate with whales

If you wanted to decode a language spoken in brief bursts by a whale species that disappears into the deep for an hour at a time, audio alone would not cut it.

You would need to know who was speaking, where they were, and what was happening at that exact moment.

That is the challenge behind Project CETI (Cetacean Translation Initiative), which aims to uncover structure and meaning in the click-based communication of sperm whales.

The goal goes beyond recording sounds. Researchers want enough context for artificial intelligence to spot patterns that could resemble words, grammar, or even syntax.

Recorder built for whale communication

To make that possible, engineers at Harvard’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have built a new kind of biologger.

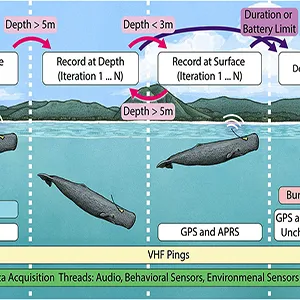

The team devised a soft-clinging, high-fidelity recorder that rides along with whales, gathers their click-based “codas,” and pairs those sounds with what the animals are doing and where they are.

The device has already survived deep dives off Dominica and is engineered specifically to generate dense, synchronized datasets that artificial intelligence systems can learn from.

“When we were looking to decode the language of whales, a key value was to have the mics placed at the best spots, for the best audio recording possible,” said first author Daniel Vogt, a lead Harvard SEAS engineer for Project CETI.

“We looked at the state of the art, what was available out there, and there was nothing that really matched what we were looking for. So we made our own.”

Listening beyond human hearing

The tag attaches using gently engineered suction cups – designed by Harvard robotics researchers to mimic the iron-grip geometry of clingfish – allowing it to adhere without harming the skin.

Inside, three synchronized, wide-band hydrophones capture click trains from multiple individuals at once, enabling researchers to triangulate who is “speaking” and at what distance.

A full sensor suite records depth, acceleration, orientation, temperature, and light, while GPS tracks positions during surfacing.

The battery lasts about 16 hours, and the audio front end is sensitive well beyond the upper limits of human hearing. In short, it is a purpose-built platform for pairing sound with context, the basic currency of language science.

Legacy tags gave bioacoustics its first huge archive of whale sounds. CETI’s logger stands on those shoulders but it goes further.

The biologger captures precise, multi-channel, time-locked streams that machine learning needs to disentangle overlapping whale communication and link acoustic structure to behavior.

Opening access to whale communication

Just as important as the hardware is how it’s shared. The team designed the entire system – electronic components, firmware, and software – to be open-source.

“This really democratizes and opens up the field of marine science, to biologists across the world,” said David Gruber, founder and lead scientist of Project CETI.

The choice lowers barriers for labs that want to study other cetaceans, or even other vocal species, without reinventing the technology stack or jostling over proprietary tools.

Finding structure in whale clicks

Sperm whale codas sound to us like metronomic clicks. To an algorithm trained on weeks of continuous recordings synchronized with behavior and location, those clicks become features: timing patterns, frequency micro-structures, and turn-taking dynamics that hint at an underlying system.

That is the point of the biologger’s design. Rather than just amassing pretty spectrograms, it weaves each acoustic event into a narrative thread: who produced it, how far away, during which posture, at what depth, amid what social configuration.

With enough of those threads, modern models – from unsupervised clustering to large sequence learners – can start to spot signatures of an “alphabet,” phoneme-like units, or higher-order structure that a human analyst would likely miss.

The approach is working. Early CETI papers have reported evidence for a sperm whale “alphabet,” along with vowel-like and diphthong-like elements in their clicks.

Together, these findings suggest that what we casually call “clicks” may actually be combinable, contrastive units within a rich acoustic system.

Research at the ocean’s limits

Whale tagging sounds romantic. It is mostly logistics and grit. Sperm whales can dive a mile deep and stay submerged for an hour, surfacing for only minutes.

The CETI team uses autonomous drones to scout, predict surfacing, and tag without harassment.

The suction cups have to hold in a heaving sea. The tags must be recovered reliably. Then there is the data deluge. Hours of multi-stream audio and motion tracking must be aligned, scrubbed, and annotated before algorithms ever see it.

Adhesion, retrieval, and synchronization – each problem needed a bespoke solution. In Robert Wood’s lab at Harvard, which leads CETI’s robotics component, Vogt and colleagues iterated the suction mechanics and packaging.

In parallel, computer scientist Stephanie Gil built a reinforcement-learning framework for those drone “find and forecast” missions.

Meanwhile, CETI’s linguistic lead, Dr. Gašper Beguš, has helped shape the modeling pipeline that connects raw waveforms to plausible linguistic hypotheses.

Translating whales takes a village

Founded in 2020, Project CETI is the largest attempt yet to bridge species with technology. Eight institutions and about 50 researchers span AI, natural language processing, cryptography, linguistics, marine biology, and robotics.

That breadth isn’t window dressing; it’s necessary. You need field biologists who can read whale behavior.

You also need engineers who can capture the right signals and modelers who can test whether those signals carry the statistical signatures of language rather than noise.

“This technology could now be expanded to millions of other species we share the planet with,” Gruber said. “I see this as a massive moment, because the field of bioacoustics and artificial Intelligence can now vastly expand.”

Future of whale communication

Today’s milestone is clarity and scale: clean, synchronized recordings that let algorithms tease apart who said what, where, and when.

Tomorrow’s milestone may be semantics: tying whale communication codas to specific behaviors or social contexts in a way that stands up across individuals and pods.

Beyond that lies the boldest idea of all – interactive experiments that test whether whales respond predictably when we “speak back” using the structures the models uncover.

That’s a long way off, and the team is realistic about the complexity. Still, the tools have finally caught up with the ambition.

The whales don’t visit once an hour. They live here. With the right microphones in the right places, and a careful, open-science pipeline, we may be able to do more than listen. We may be able to understand.

The study is published in the journal PLOS One.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–