When neighborhood pets refuse to drink tap water, take immediate precautions

The drinking water in New Freeport, Pennsylvania, changed suddenly when a nearby shale gas well malfunctioned underground. A new study now links that single accident to contamination in dozens of private wells that supply this small Greene County village.

For families who watched pets avoid their bowls and saw brown streaks in their sinks, the results match what they have lived with for years. Many households no longer trust the water from their own taps for drinking, cooking, or bathing.

Gas wells and drinking water

The work was led by John F. Stolz, a microbiologist at Duquesne University and senior author of the new study. His research focuses on how oil and gas development changes the chemistry of drinking water in rural communities.

The Center for Coalfield Justice, a local environmental group, called Stolz about strange odors and discoloration in New Freeport wells.

Residents also reported that their dogs and cats suddenly refused to drink from bowls filled at the kitchen sink.

Within months, at least 22 households were relying on large holding tanks known locally as water buffaloes to get through each day.

Others filled five-gallon jugs so they could haul in clean water from outside town or from donations organized by neighbors.

What is a frac-out?

To understand what went wrong, it helps to know how hydraulic fracturing, a method that uses high-pressure fluid to crack deep rock and release gas, usually works.

In normal operations, the pressurized mixture stays inside steel and cement casings several thousand feet below the surface.

During the drilling campaign, that system failed and a frac-out, an accident where pressurized fracking fluid escapes into unwanted pathways, occurred beneath New Freeport.

The fracking fluid forced its way into an abandoned gas well thousands of feet from the main bore and sent a muddy fountain of gas and liquid to the surface.

Pennsylvania has hundreds of thousands of abandoned and orphaned oil and gas wells scattered across its hills.

Many are unmapped or poorly recorded, which leaves hidden shortcuts for pressurized fluids to reach shallow aquifers, underground rock layers that store and move groundwater.

What the study found

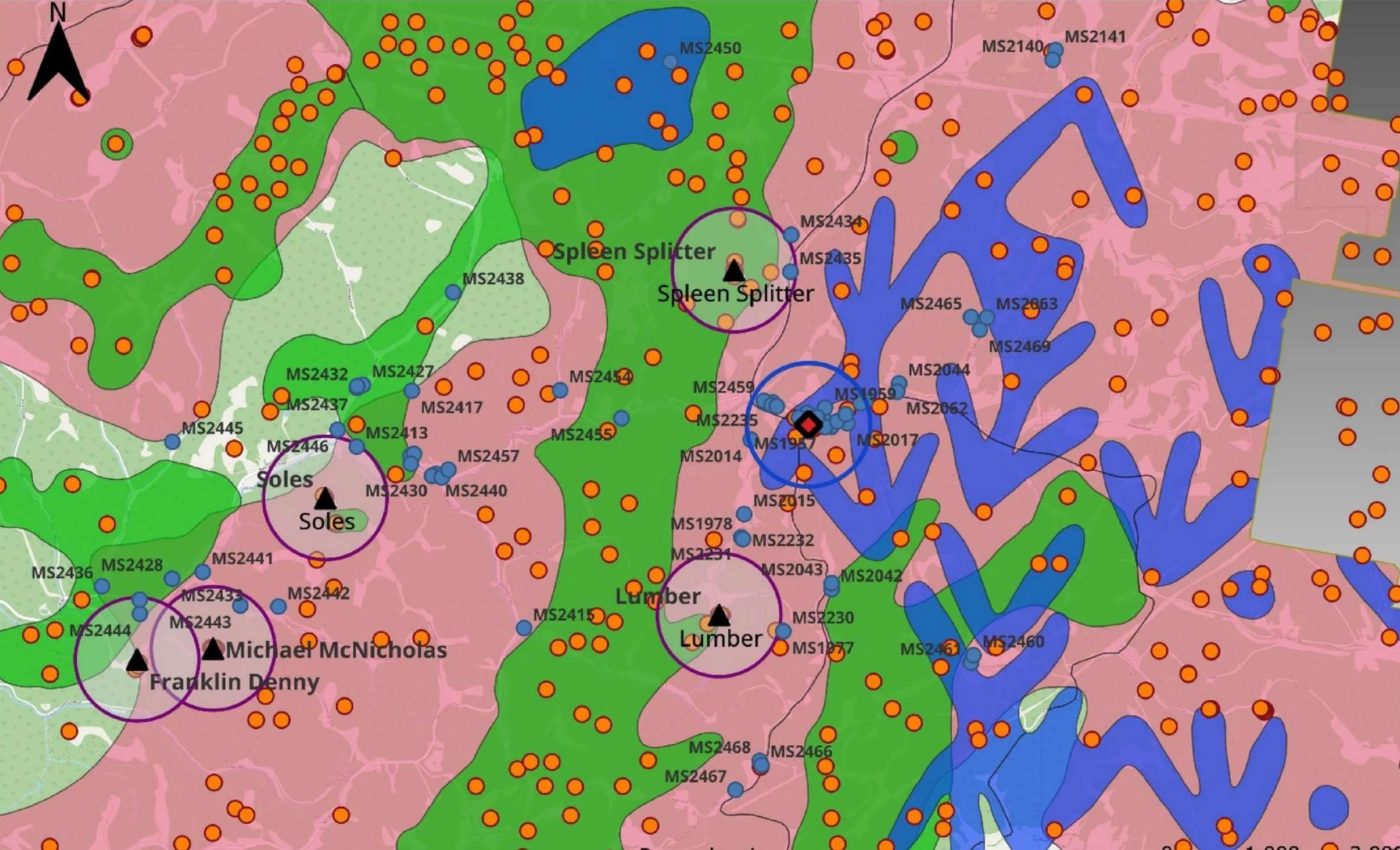

In a study, researchers sampled 75 private wells and nearby streams for almost two years after the frac-out. They measured dissolved gases and salts that act as fingerprints of oil and gas waste mixing with fresh groundwater.

A key tool in the project was the Multi-component Contamination Index, a combined score that flags water altered by oil and gas brines.

When the team mapped index scores across the landscape, many of the most strongly affected wells clustered in stream valleys where fractured rock naturally directs groundwater flow.

The researchers also followed a preponderance of evidence, a standard that weighs several different clues instead of relying on a single test.

Their work shows that this frac-out was one of at least 54 similar communication incidents recorded in Pennsylvania between 2016 and 2024, and that its impacts stretched beyond the 2,500-foot zone where drilling is normally presumed to affect water quality.

Gas leaks into water from wells

The team also found methane, a flammable gas that can build up in enclosed spaces, in 71 percent of all the samples they collected.

State health officials warn that dissolved methane around 28 milligrams per liter can create an explosion risk inside small structures that contain wells or plumbing.

Two of the wells in New Freeport reached what the researchers classified as explosive methane levels, far above that warning range.

Across Pennsylvania, more than a quarter of adults rely on private wells as their primary drinking water source. That leaves millions of people depending on water that is not routinely tested by government agencies before it reaches their taps.

Pennsylvania is also unusual because it has no statewide construction or testing standards for private wells, even though they serve so many residents.

Homeowners must decide when to test, how to treat problems, and how to respond when agencies conclude water is unsafe but decline to link it directly to nearby drilling.

For people in New Freeport, those gaps in protection feel very personal, as some wells have turned foul while others have gone dry.

Drinking water, gas wells, and safety

Some residents have installed treatment systems, while others depend on five-gallon jugs or delivered tanks that can cost thousands of dollars a month.

Local officials now urge anyone living near active or proposed gas development to pay for baseline tests before drilling begins, even if that means spending around seventy five dollars for an oil and gas panel.

Scientists add that better detection of tracers, chemical markers that reveal even small amounts of oil and gas brine in fresh water, would give communities stronger evidence when they seek help.

New Freeport’s story shows that a single frac-out can reshape drinking water far beyond the edges of a drill pad. It also raises a harder question for communities across Pennsylvania that depend on private wells: what happens when the water that defines a place can no longer be trusted.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–