Scientists explain why living to be 100 years old is becoming less likely in today's world

The rise in life expectancy that defined the first half of the 20th century is losing steam. A new analysis of 23 wealthy, low-mortality countries finds that generations born after 1939 will keep living longer.

The gains will be smaller, however, and no cohort in that period is projected to average 100 years of age.

In other words, expect progress – just not the kind that vaulted average lives forward by decades in your great-grandparents’ time.

Why life expectancy soared

From 1900 to 1938, cohort life expectancy in rich nations surged by roughly five and a half months with each successive birth year.

A person born around 1900 could expect to live about 62 years on average; by the late 1930s, that figure hovered near 80.

That leap wasn’t magic. It came from clean water and sanitation, safer childbirth, vaccines, antibiotics, better nutrition, and fewer deaths from infectious diseases – especially in infancy and childhood.

When large numbers of people stop dying young, the average shoots up.

Longevity slowed after 1939

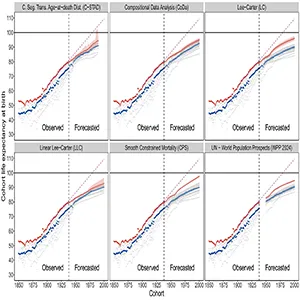

For those born from 1939 onward, the slope flattens. Depending on the statistical model, gains shrink to about two and a half to three and a half months per birth year.

Longevity is still rising, but we’ve harvested the “low-hanging fruit.”

Infant and child mortality are already extremely low in these countries, so further progress depends on pushing back deaths at older ages – slowing heart disease, cancers, dementia, diabetes, and chronic lung disease.

That work tends to advance in careful increments: better prevention, earlier diagnosis, safer surgeries, steady medication improvements.

Even if survival at older ages improved at twice the pace current models project, the study suggests we still wouldn’t recreate the turbocharged gains of the early 20th century.

How to study human life expectancy

A key strength of this research is its focus on cohort life expectancy – the average lifespan of people born in the same year – rather than period life expectancy, which is a snapshot of mortality in a single calendar year.

Cohort forecasts track how risks evolve across a generation’s life course, so they’re less distorted by short-term shocks.

The authors pulled from the Human Mortality Database and ran six independent forecasting techniques to stress-test the results. Across models and countries, the story stayed the same: still climbing, just more slowly.

Generations fall short of 100

Here’s the headline result: on average, none of the cohorts born after 1939 in these high-income settings are expected to reach 100.

That doesn’t mean there won’t be lots of centenarians. There will be – and more of them as medicine and living standards improve.

But the average for an entire birth cohort won’t hit triple digits. Even for those born in 1980 – a generation that benefited from modern cardiology, oncology, trauma care, and safer cars – projection curves fall short of a 100-year mean.

Rethinking long-term plans

A world of slower longevity gains still demands planning. Many pension systems, retirement ages, and healthcare budgets implicitly assume early-century momentum will continue. If the pace is gentler, those assumptions need updating.

For individuals, it’s a nudge to reality-check expectations you might have borrowed from your grandparents’ dramatic era of improvement.

Financial planning, retirement timing, and long-term care decisions should reflect steady, incremental gains rather than another once-in-a-century leap.

There’s also a policy message hidden in the trend lines. When the big wins came from eliminating early deaths, public health could deliver spectacular gains with a few broad interventions.

Now the hard work is chronic-disease grind: lowering blood pressure and LDL at scale, reducing smoking and harmful drinking, curbing obesity and diabetes, cleaning the air, and closing gaps by income and education.

Those efforts aren’t flashy, but they move the average the only way it moves in mature health systems – slowly, year after year.

Life expectancy predictions

Longevity projections aren’t prophecies. The past few years alone have shown how the unexpected can jolt trends: COVID-19 pushed mortality up in many places; opioids and alcohol have done the same in some populations.

Equally, breakthroughs could bend curves down – better cancer screening and treatment, safer and more effective obesity therapies, progress against dementia.

The point of the new work isn’t to declare those off the table. It’s to set a realistic baseline: if nothing transformative arrives, don’t bank on a return to early-century velocity.

Building healthier futures

Lean into the unglamorous fundamentals. Keep tightening control of hypertension and diabetes. Make it easier – and cheaper – for people to eat nutritious food and move their bodies.

Expand vaccination and evidence-based screening. Clean up air and reduce workplace and roadway risks.

Invest in primary care, community health, and mental health, because all three are deeply entwined with chronic disease.

Also, be relentless about equity: the biggest, fastest longevity gains available today come from lifting the worst-off closer to the best-off.

The headline isn’t that progress is over. It’s that the era of giant, easy wins ended decades ago. Longer, healthier lives are still within reach, but the rocket ship boom phase of longevity increases has passed.

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–