World’s largest sinkhole showcases the power and beauty of nature

Peering over the forest-draped ridges of southwestern China, a scar nearly half a mile wide across yawns open, so sheer that light seems to drain straight into the earth. Xiaozhai Tiankeng, also known as the “Heavenly Pit,” is the world’s largest sinkhole.

Locals have spoken of Xiaozhai Tiankeng for centuries, yet it was only “discovered” by the wider world in 1994 when a team of British cavers stumbled on its hidden maw.

Measured from rim to floor, the Xiaozhai Heavenly Pit plunges about 2,172 feet – deeper than a stack of six Statues of Liberty – and encloses roughly 4.2 billion cubic feet of space.

Those numbers secure its place as the planet’s deepest and largest known sinkhole, a title it wears with quiet, vertigo-inducing confidence.

Xiaozhai Tiankeng – a hidden giant

Geologists now read the sinkhole’s striped limestone walls like pages in an epic timeline. Rainwater, slightly acidic after mingling with soil carbon dioxide, seeped through fractures in Triassic-age rock for some 128,000 years.

Bit by bit, it hollowed out caverns below Fengjie County, until the ceiling finally collapsed and birthed the chasm seen today.

Because the limestone lies high above sea level and is free of clay impurities, water could tunnel unimpeded, carving passages that still channel underground streams.

The Xiaozhai Tiankeng stands as the textbook example of karst topography – what happens when karst processes are given perfect working conditions – and plenty of monsoon rain.

Understanding karst topography – the basics

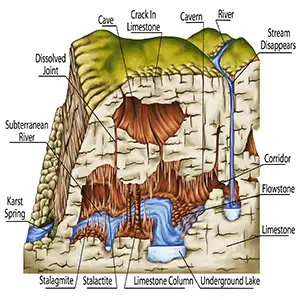

Karst topography forms when water slowly eats away at soft, soluble rocks like limestone, dolomite, or gypsum. As rainwater seeps into the ground, it picks up carbon dioxide and turns slightly acidic. That weak acid reacts with the rock, gradually wearing it down.

Over time, the land above starts to sag and collapse, creating sinkholes, disappearing streams, and vast cave systems below the surface. It’s a quiet, powerful transformation that reshapes the landscape from the inside out.

How Xiaozhai Tiankeng got its name

Chinese researchers classify this colossus as a tiankeng, a term reserved for sinkholes at least 328 feet deep and wide, each harboring a river at its base.

The word translates variously as “heavenly pit” or “sky hole,” both fitting nods to the feeling one gets while peering over the edge. Of the 75 such features documented worldwide, about 50 cluster inside China’s humid karst belts.

The Xiaozhai example dwarfs its peers: it stretches roughly 1,676 to 2,054 feet long and 984 to 1,762 feet across, dimensions that defy easy comparison yet satisfy every benchmark geologists set for these rare landforms.

Long, layered, steep descent

Two enormous “bowls” stack inside the chasm, each dropping more than 984 feet before giving way to the next terrace.

After heavy summer storms, a temporary waterfall pours over the rim and ribbons down the vertical walls, then vanishes into the stone.

Where the stream briefly reappears, it leaps in a single 151-foot plunge that echoes through the darkness below.

Scrambling down is a workout: concrete stairways cling to corners of the cliff, but many scientists still rope in, carrying sensors and sampling kits on their harnesses.

The sense of scale – walls so high the sky shrinks to a blue rectangle – never quite fades.

Life inside Xiaozhai Tiankeng

Sunlight weakens but never disappears, nurturing a green haze of ferns, mosses, and towering ginkgo biloba trees.

Biologists have counted 1,285 plant and animal species in this natural greenhouse, including the elusive clouded leopard, whose total wild population is thought to number fewer than 10,000.

Dense humidity and steady temperatures create a pocket climate unlike anything on the surrounding plateau.

Winged insects flit among orchids; amphibians breed in clear pools; vines cling to walls slick with mist.

Each tier supports its own community, separated by the same height difference that splits mountain life into bands. To ecologists, the pit is a ready-made laboratory for studying evolution in vertical space.

A river runs through it

Near the foot of the second bowl, the Difeng cave yawns open, swallowing a crystal stream that has already traveled 5.3 miles underground.

The water’s final above-ground act is that 151-foot curtain, after which it threads the darkness beneath the sinkhole and resurfaces downstream at the cliffs of the Migong River.

Flow-rate monitors reveal seasonal surges that match regional rainfall, tying surface weather to hidden hydrology.

Mapping that labyrinth has never been easy. Speleologists tried five times in a decade to trace the torrent from end to end; each expedition turned back amid roar and spray, equipment battered by sudden rises in water level.

The cave remains one of China’s least charted river systems, a reminder that even in the GPS era some coordinates resist tidy lines.

Karst topography and Xiaozhai Tiankeng

Field teams from Chongqing’s Institute of Karst Geology, often joined by overseas colleagues, now lower radar probes, deploy microclimate loggers, and sample sediments for isotopic clocks that refine the sinkhole’s birth date.

Their findings feed global climate models and offer clues to safeguarding groundwater in limestone regions where pollution can spread in hours.

Yet the pit keeps its mystique. Nearby villagers swap tales of dragons curling inside the void or celestial doors hidden behind the waterfall.

Trekkers on the steep trail say the silence at the bottom feels otherworldly, broken only by dripping water and the occasional flap of a bat.

Maybe that mix of hard data and lingering legend is why the Xiaozhai Tiankeng continues to draw scientists, adventurers, and curious travelers alike – each hoping to understand, if only for a moment, how water, rock, and time conspired to open a doorway straight through the Earth’s surface.

This story was adapted from a report by the BBC, which you can watch here…

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–