New study on Y chromosome disappearance finds direct link to much greater cancer risk

Men inherit their Y chromosome much the way families pass down a favorite pocketknife – practically unchanged from father to son. For decades, biologists treated this tiny stretch of DNA as little more than a switch for making testes.

Recent work flips that idea on its head. The Y chromosome turns out to influence immune function, cancer risk, and even how long a man might live.

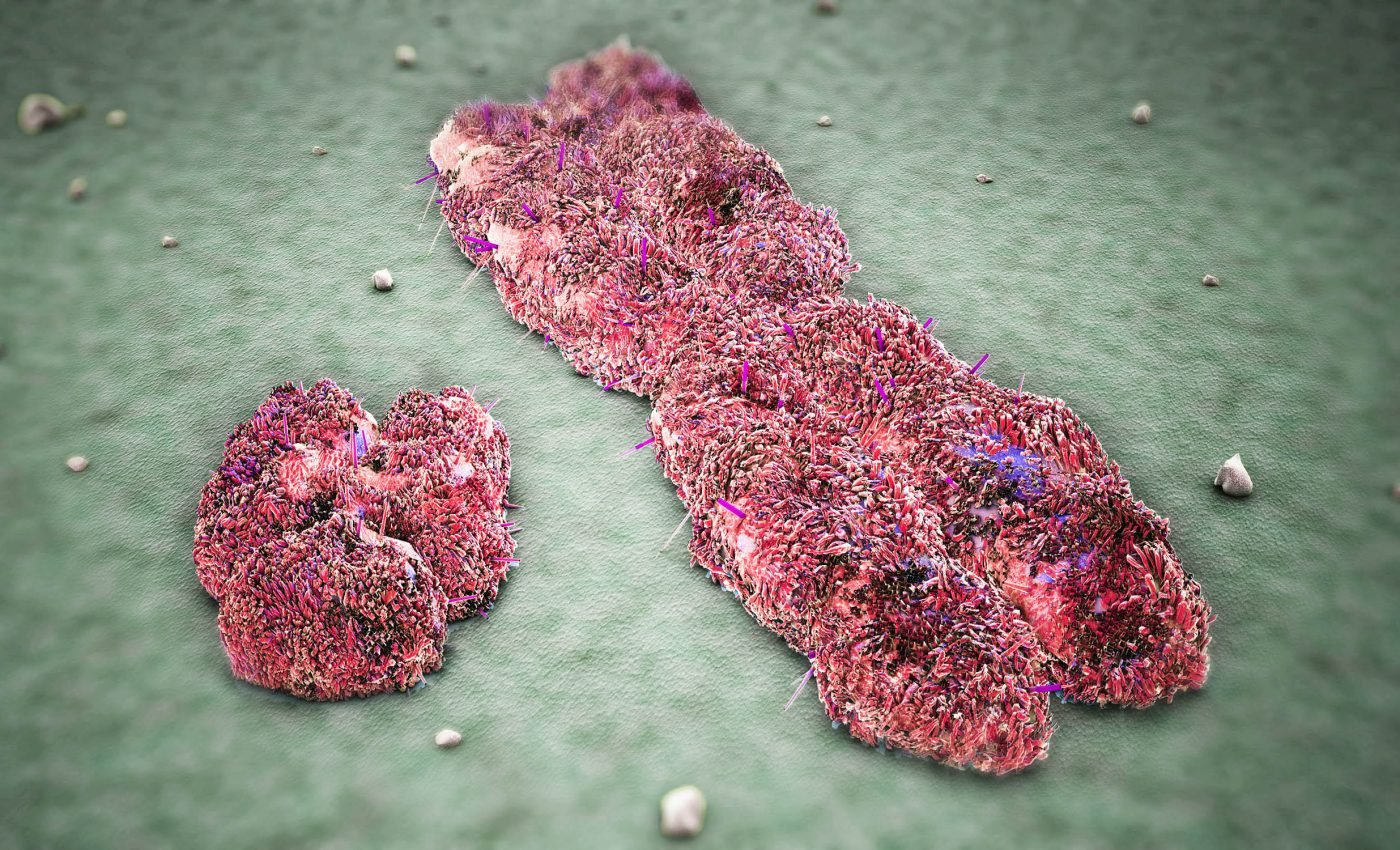

Scientists once assumed its limited gene set made it a genetic lightweight. The X chromosome carries more than a thousand genes, yet the Y chromosome contains only about fifty to seventy protein-coding genes.

Size, however, doesn’t tell the whole story. By following the Y’s trail through aging blood cells, researchers are charting an unexpected route from missing DNA to stubborn tumors.

Why the Y chromosome matters

The Y chromosome sprang into the spotlight a century ago when geneticists linked it to male sex determination.

Its SRY gene directs an embryo’s early tissues to form testes, setting off a hormonal cascade that produces typical male anatomy.

Beyond that first task, the Y shoulders other jobs – guiding sperm formation, shaping certain brain circuits, and engaging with immune genes on the X chromosome.

Because the Y is passed down intact, it serves as a molecular time capsule. Anthropologists trace paternal lineages back tens of thousands of years by decoding tiny changes in its sequence.

Clinicians, meanwhile, focus on what happens when the Y goes missing altogether in some cells – a phenomenon called loss of Y, or LOY.

Loss of Y (LOY)

LOY rises steeply after middle age. Surveys of European and American blood banks show that fewer than 2 percent of men under forty carry Y-negative blood cells, but the figure balloons past 40 percent by the late seventies.

Smokers hit those levels even sooner. Despite its frequency, LOY often flies under the radar because routine blood panels do not look for mosaic chromosomal loss.

The disappearing Y appears to chip away at healthy aging. Population studies link LOY to higher mortality from cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s-like dementia.

One Swedish project calculated that men with heavy LOY lived, on average, 5.5 years less than peers whose cells kept their Y.

The chromosome’s dwindling presence seems to impair immune surveillance, setting the stage for rogue cells to thrive.

Link between cancer and Y chromosome loss

In the new study co-authored by Dr. Dan Theodorescu, director of the Cancer Center at the University of Arizona, researchers mapped Y chromosome loss across thousands of individual cells from human cancers and matched mouse models.

They found that Y-negative cells were not limited to the tumors themselves; they also dominated the surrounding immune landscape.

CD4⁺ helper T cells shifted toward a regulatory identity that dampens attack signals, while CD8⁺ killer T cells lost much of their punch.

The degree of LOY in the bloodstream mirrored what the team saw inside the tumor. Patients whose blood showed a high percentage of Y-negative white cells tended to harbor tumors rich in LOY and faced poorer outcomes.

Those correlations held across lung, bladder, and head-and-neck cancers, hinting at a common mechanism rather than a disease-specific quirk.

Watching LOY in the cancer ecosystem

The work was led by Lars A. Forsberg at Uppsala University’s Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology, with collaborators at Karolinska Institute and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

His group has spent the last decade cataloging how the vanishing Y shapes male health beyond reproduction.

By combining single-cell RNA sequencing with CRISPR-engineered mouse tumors, the researchers could watch LOY spread through the cancer ecosystem in real time.

Forsberg’s earlier epidemiological studies set the stage, but the present findings move from pattern spotting to mechanistic insight.

The team now proposes that Y-negative tumor cells may release vesicles carrying factors that nudge nearby immune cells toward the same chromosomal loss, blunting the body’s response on multiple fronts.

Cancer care and the lost Y chromosome

Immune-based therapies such as CAR-T cells rely on harvesting a patient’s own T cells, engineering them to recognize cancer, and then infusing them back.

If those starting cancer cells already lack the Y chromosome, their fighting spirit may be compromised before treatment even begins.

Routine LOY screening could help oncologists decide whether to enrich for Y-positive cells or explore alternative strategies.

The study also raises the possibility of a simple blood test that flags men at higher risk years before a tumor forms.

By tracking LOY alongside traditional markers like PSA or C-reactive protein, clinicians might refine screening schedules and lifestyle advice, especially for heavy smokers or men with family histories of cancer.

Open questions that need answers

Although the association between LOY and worse survival is strong, causality still needs proof. Lab groups are now using gene-editing tools to delete the Y in naïve T cells and watch how tumor control changes in animal models.

Others are probing whether antioxidants, exercise, or smoking cessation can slow the march of LOY in circulating blood cells.

Another unknown is why certain chromosomes – particularly the Y – drop out more readily than others.

One theory points to its structure: lacking a second copy for recombination, the Y may struggle to repair damage from oxidative stress or environmental toxins.

Pinning down the exact triggers could open doors to interventions that keep the chromosome intact longer.

Y chromosomes, cancer, and the future

The Y chromosome may be small, but its absence echoes throughout a man’s biology. Loss of Y tampers with immune cells, helps tumors dodge attack, and shortens healthy years.

As laboratories refine single-cell tools and clinicians adopt more personalized cancer therapies, checking whether the Y is present or missing could become as routine as measuring blood pressure.

From sex determination in the womb to survival in old age, this pint-sized chromosome punches well above its weight, reminding us that in genetics, size isn’t everything.

The full study was published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–