Scientists say this teenage dinosaur used its fancy skull dome for mating

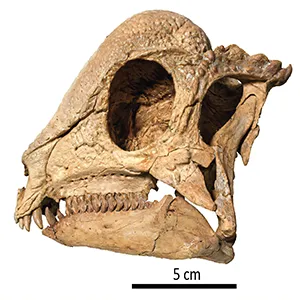

A small, “teenage” dome-headed dinosaur from Mongolia has turned up with a big story to tell. The fossil belongs to a brand-new species, Zavacephale rinpoche, and is the oldest definitive member of its group ever found. It also represents the most complete skeleton of its kind.

Even more striking, this youngster already carried a fully formed skull dome. That gives scientists a rare glimpse into how these dinosaurs grew and showed off.

The discovery, reported in the journal Nature, comes from a team working in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert.

“Pachycephalosaurs are iconic dinosaurs, but they’re also rare and mysterious,” said Lindsay Zanno, associate research professor at North Carolina State University (NCSU) and head of paleontology at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences.

The new species name, Zavacephale rinpoche, reflects its roots: zava means “origin” in Tibetan, while cephal comes from the Latin for “head.”

The species name rinpoche – Tibetan for “precious one” – honors its domed skull, which once gleamed on a cliff face like a polished gem.

Zavacephale rinpoche fossil discovery

The fossil came from the Khuren Dukh locality in the Eastern Gobi Basin. In the Early Cretaceous, around 108 million years ago, lakes dotted this valley, and escarpments edged its sides.

Pachycephalosaurs were herbivores. Adults of related species could grow to roughly 14 feet long and about 7 feet tall.

They weighed between 800 and 900 pounds. By comparison, this specimen was just three feet long and continued to grow.

“Zavacephale rinpoche predates all known pachycephalosaur fossils by about 15 million years,” said Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences – now a research assistant at North Carolina State University

“It was a small animal – about three feet or less than one meter long – and the most skeletally complete specimen yet found.”

Juvenile with an adult-style dome

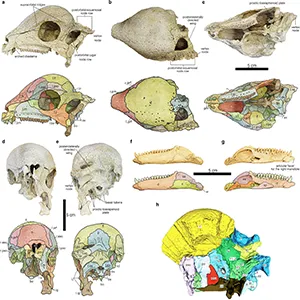

Although not fully grown, the pachycephalosaur’s skull already sported a finished dome, without the extra knobs and spikes seen in later, larger relatives.

That combination – young body, mature-looking dome – lands right in the middle of a debate: which differences in pachycephalosaur skulls mark separate species, and which simply track growth?

“Z. rinpoche is an important specimen for understanding the cranial dome development of pachycephalosaurs, which has been debated for a long time,” Chinzorig said.

Estimating dinosaur age

These dinosaurs are famous for flashy headgear, but scientists need more than style points to sort species or ages.

“Pachycephalosaurs are all about the bling, but we can’t use flashy signaling structures alone to figure out what species they belong to or what growth stage they’re in because some cranial ornamentation changes as animals mature,” Zanno explained.

Normally, age is estimated by reading growth rings in bones, which is difficult when most finds are only partial skulls.

Here, the skeleton includes limbs as well as a complete skull, letting the team link bone age and dome form directly.

“We age dinosaurs by looking at growth rings in bones, but most pachycephalosaur skeletons are just isolated, fragmentary skulls,” Zanno said.

“Z. rinpoche is a spectacular find because it has limbs and a complete skull, allowing us to couple growth stage and dome development for the first time.”

A thin slice of the lower leg bone shows the animal died as a juvenile, even though its dome was already in place.

Not for battle, but display

Illustrations usually show pachycephalosaurs locked in headbutting battles. The evidence points elsewhere. According to Zanno, the consensus is that these dinosaurs used the dome for socio-sexual behaviors.

“The domes wouldn’t have helped against predators or for temperature regulation, so they were most likely for showing off and competing for mates,” noted Zanno.

“If you need to headbutt yourself into a relationship, it’s a good idea to start rehearsing early.”

Lessons from Zavacephale rinpoche

By pushing the record of the group back at least 15 million years and arriving nearly complete, Zavacephale rinpoche fills major gaps in both timing and anatomy.

Hands are almost never found in this group, but here they are intact. The specimen also preserves a full tail with its tendons still in place, along with gut stones the animal used to grind plant matter.

These rare details give scientists new clues for reconstructing the group’s body plan, movement, and diet.

“This specimen is a once-in-a-lifetime discovery,” Zanno said. “It is remarkable for being the oldest definitive pachycephalosaur, pushing back the fossil record of this group by at least 15 million years.”

“Z. rinpoche gives us an unprecedented glimpse into the anatomy and biology of pachycephalosaurs, including what their hands looked like and that they used stomach stones to grind food.”

A skull dome gleaming from a Gobi cliff led to the earliest and most complete pachycephalosaur yet. Even juveniles had full domes, reframing dinosaur growth and extending their timeline deep into the Early Cretaceous.

For a group long known only from fragments, Zavacephale rinpoche reads like a full-length chapter – and it changes the plot.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–