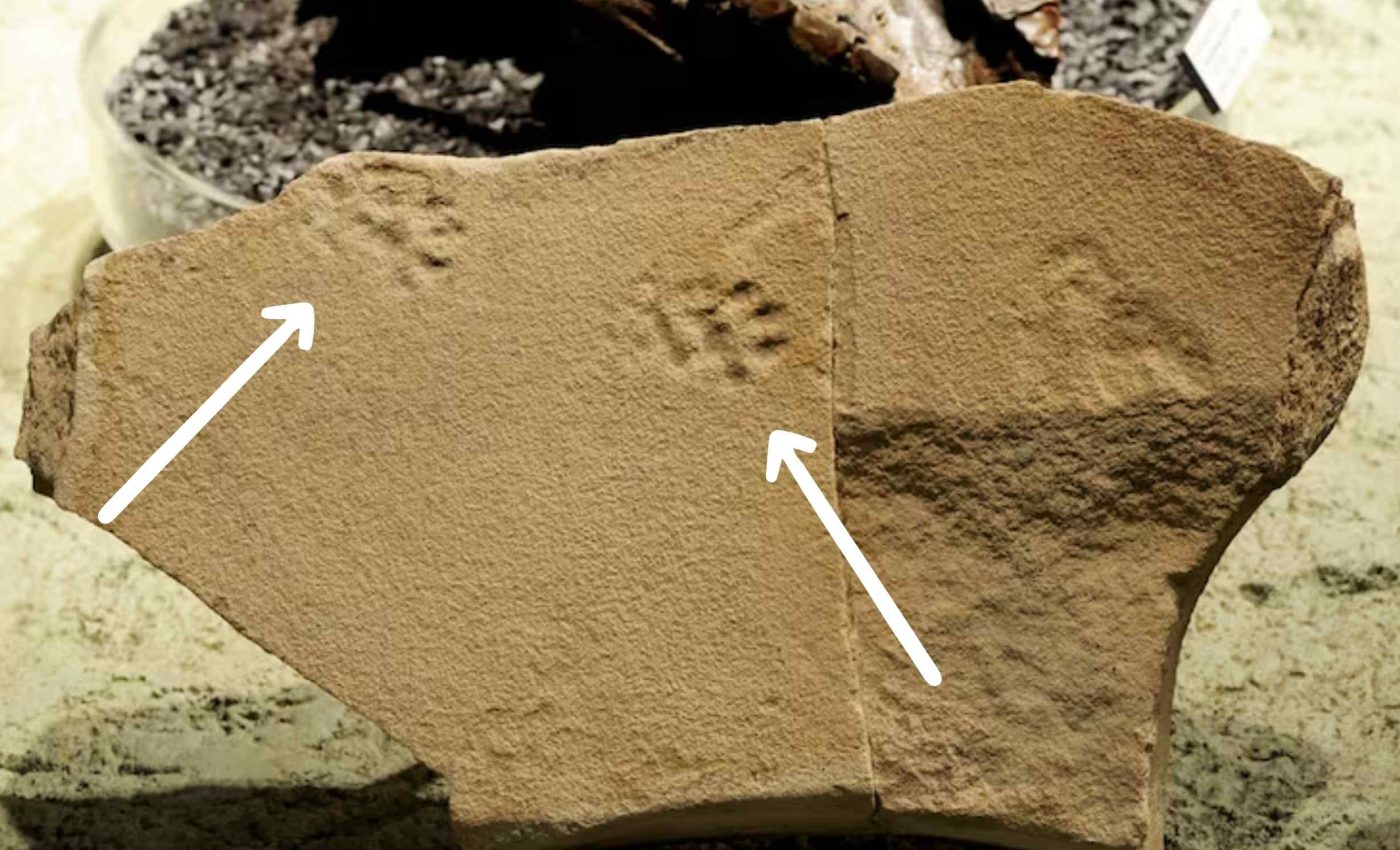

29-million-years ago, a cat with retractable claws left paw tracks in this volcanic ash

A new study analyzed four sets of fossil footprints, including cat-like tracks in 29-million-year-old volcanic ash at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument in Oregon. The trackmaker was bobcat size, and the impressions lack claw marks.

Two other slabs capture bird foraging and a lizard’s sprint from about 50 million years ago. Together they turn a fossil rich site into a record of behavior.

Lead researcher Conner Bennett of Utah Tech University led the work. A trace fossil captures action rather than anatomy.

“Body fossils tell us a lot about the structure of an organism,” said Bennett, contrasting these traces with bones.

3D models of ash tracks

The team used photogrammetry, a method that stitches overlapping photos into accurate 3D shapes, to document each track. This approach let them zoom in without losing detail.

They mapped each surface as a digital elevation model, a color shaded guide to tiny height changes. That made faint beak marks and claw tips stand out clearly.

They also preserved the slabs digitally for future work. Researchers can now remeasure toe-spacing and pad size without handling the rock.

The cat-like tracks formed in fresh ash about 29 million years ago. A round central pad, four toe ovals, and no claw marks point away from dog-like feet.

Those traits compare well with a nimravid, an extinct cat-like carnivore with saber teeth, known from this formation. The size matches Hoplophoneus, a bobcat sized predator in the region.

The team is cautious about pinning a species to a track. Still, the combination of size and shape is a tight fit.

How volcanic ash froze footsteps

Volcanic eruptions in prehistoric Oregon did more than shape the landscape. They also helped preserve moments of life with remarkable precision.

When fine ash settled after an eruption, it created a smooth, soft surface that quickly hardened once footprints pressed into it and the next layer of ash sealed it shut.

Over time, minerals replaced the original sediment, turning fragile imprints into stone. That process explains why the feline, bird, and lizard tracks at John Day survived for tens of millions of years.

Each footprint is a geologic accident that captured an instant of motion, proof that fire and destruction can also act as a preservative for life’s smallest details.

Many animal tracks in the ash

A small avian trackway sits beside peck marks and winding worm trails. This setting in lakebed sediment with calm water preserved delicate traces.

Another slab records a running lizard, with splayed toes and sharp claw impressions. It comes from the upper Clarno Formation and dates to roughly 50 million years ago.

The bird traces show a foraging style that matches living shorebirds. Stability in such behavior across deep time is unusual but not unheard of.

Three-toed heavyweights

Rounded three toed prints suggest a large perissodactyl, an odd toed hoofed mammals such as early rhinos or tapirs. The shape fits well with the hoofed animals known from nearby bones.

The monument spans nearly 14,000 acres in central and eastern Oregon. Its rock layers preserve a long record from the Eocene into the Miocene.

Putting tracks next to skeletons narrows the options for who lived where and when. It also reduces guesswork about daily actions, like stalking or probing mud.

Footprints capture moments that skeletons miss. A paw whispering across fresh ash tells you about quiet movement long before you see teeth.

Several slabs had waited in storage for decades before digital reanalysis. New imaging pulled more information from surfaces first collected in 1979 and 1987.

What the cat prints actually show

The absence of claw marks matters. Cats tuck claws to keep them sharp and quiet, while dogs cannot, and that difference often shows up in tracks.

Pads look rounded rather than triangular, and toe tips are blunt. Those features are typical of feliform feet and help separate them from canids.

Researchers avoided over claiming identity. A match to Hoplophoneus remains a best fit based on size and known local fauna.

Lessons from the ash tracks

Beak marks beside worm trails say the bird probed soft mud for invertebrates. The proximity of traces hints at search patterns similar to modern shorebirds.

The lizard print shows speed and splayed toes, a common response to slippery surfaces. Sharp claw traces add confidence that it was a running reptile, not a mammal.

Behavioral evidence helps test climate and habitat reconstructions drawn from plant and animal fossils. Small details, like mud firmness, speak to water depth and energy.

“Trace fossils are really key in helping us to better understand,” said Bennett. They remind us that even the smallest marks in stone can speak volumes about how life once moved, fed, and survived in a world long gone.

The study is published in Palaeontologia Electronica.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–