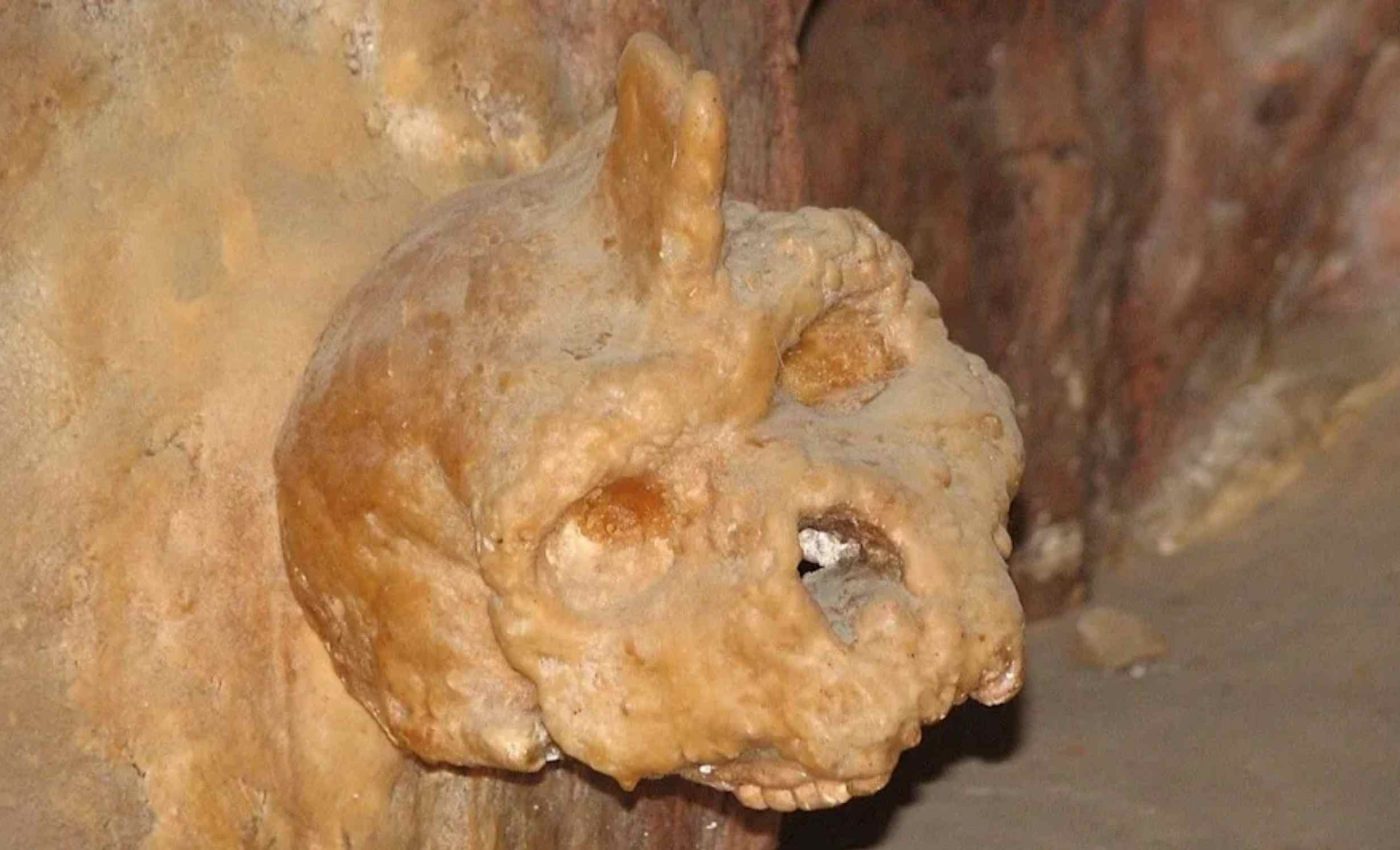

300,000-year-old skull discovered in a Greek cave belongs to an unknown early human species

A skull from Petralona Cave in northern Greece now has a firm timeline. By measuring a crust that formed directly on the bone, researchers show it is at least 286 ± 9 thousand years old, likely near 300,000 years, and distinct from both our species and Neanderthals.

That single result pulls a long standing mystery into focus. It sets the skull within a crowded chapter of human evolution when more than one kind of human lived in Europe.

Dating the Petralona skull

The study includes work by Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London (NHM).

The precise age places the fossil among early members of a group many scientists call Homo heidelbergensis, a catchall for robust humans that predate Neanderthals and modern people.

This matters because Europe 300,000 years ago was not empty. Several populations overlapped, and fossils with mixed traits can be hard to sort without a solid clock.

The new dating nails that clock to the skull itself. It removes debates that leaned only on tools or cave layers found nearby.

How uranium tells time

The team studied a white crust of calcite that had grown on the cranium. Calcite is a cave mineral made of calcium carbonate that can trap tiny amounts of uranium as it forms.

They used uranium-series dating, which measures how uranium slowly decays into thorium in a closed system. Because the decay rate is known, the ratio between the two elements tells how long the calcite has been in place.

The calcite in question is a type of speleothem, a general term for cave formations such as stalagmites, stalactites, and stone veils. Sampling calcite that directly coats the bone avoids the guesswork that comes from loose sediments.

The authors also showed that the skull’s calcite did not grow at the same time as the calcite on the nearby chamber wall. That point keeps the age tied to the fossil rather than to disputed cave layers.

What the Petralona skull is not

A careful look shows Petralona skull lacks hallmark Neanderthal traits and is not Homo sapiens. Researchers underscored that the skull represents a different population that lived during the rise of Neanderthals.

“The new age estimate supports the persistence and coexistence of this population alongside the evolving Neanderthal lineage in the later Middle Pleistocene of Europe,” said Stringer.

The skull itself likely belonged to a young adult male, based on size and tooth wear. That observation adds a small human detail to a big evolutionary story.

A useful comparison

A study of the Broken Hill, or Kabwe, skull from Zambia estimated a best age of 299 ± 25 thousand years. Those authors concluded that Africa at the same time also hosted several hominin lineages.

That match in age is important because the Petralona skull shares overall shape with Kabwe. The comparison fits a picture in which related populations lived in Africa and Europe at roughly the same time.

Petralona, then, is not a one off. It lines up with other fossils that sit between earlier humans and later Neanderthals and modern people.

Petralona skull’s cave location

Petralona skull was reportedly found attached to a chamber wall known as the Mausoleum. The new analysis shows that the skull’s calcite crust formed after older wall coatings, not together with them.

That breaks a long assumed link between the fossil and a specific wall layer. It also helps resolve why earlier attempts at dating the site gave wildly different answers.

The team sampled calcite on the skull and from other parts of the cave. They showed that the skull’s coating belongs to a younger phase of mineral growth than the wall’s coating.

By focusing on the crust that actually touches the bone, the researchers avoided a common trap in cave sites. The result is a minimum age for the person, not just for the cave’s decoration.

Labels and lineages

Scientists use Homo heidelbergensis to group mid Pleistocene skulls that are neither classic Neanderthal nor modern.

The label is debated because fossils vary across regions, and some specimens show a patchwork of traits.

Work on a large sample from Spain’s Sima de los Huesos shows that European fossils from this time do not all fall on one track. The pattern suggests more than one lineage operated in the region.

Those findings fit with Petralona’s placement outside Neanderthals and H. sapiens. They also echo evidence that some European fossils have clear Neanderthal traits, while others do not.

That mixed landscape lowers the odds that any single skull will tell the whole story. It raises the value of firm dates tied to bones.

Petrolona skull, climate, and context

The time window for Petralona skull overlaps cool and warm swings that shaped habitats in Europe.

Researchers often track those swings using Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) numbers, a system based on oxygen ratios in ocean sediments that reflect global ice.

A solid date lets scientists compare the skull to climate curves and to tool traditions with better precision. That, in turn, helps test how shifting environments influenced where different human groups lived.

It also anchors debates about dispersals. If Petralona skull and Kabwe cluster near the same age, then connections between Africa and Europe may be tighter than some maps suggest.

Proteins or ancient DNA could help test where Petralona skull fits within the human family, though the cave setting and age make recovery hard. Improved scans and metrics can still narrow its closest relatives.

For now, the clear clock is the win. It sets the Petralona skull in the right neighborhood of time and allows fair comparisons with other skulls of similar age.

The study is published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

Image credit: By Nadina.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–