Ancient predator had a gut-wrenching strategy for adapting to climate shock

About 56 million years ago, Earth slipped into the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), a sudden global warming pulse that pushed temperatures up by at least 5°C (9°F). In the badlands of what is now Wyoming, one mid-sized predator, Dissacus praenuntius, found itself confronting a landscape in flux.

A new study led by Rutgers University suggests the animal’s solution was unexpected: when prey became scarce, it started crunching bones.

“What happened during the PETM very much mirrors what’s happening today and what will happen in the future,” said Andrew Schwartz, the Rutgers anthropology doctoral student who led the research.

The work combines field excavations in the Bighorn Basin with a forensic technique called dental microwear texture analysis (DMTA).

By reading microscopic pits and scratches on fossil teeth, the team reconstructed what the animal was chewing in the weeks before it died; tougher, deeper marks usually point to hard items such as bone.

Dissacus praenuntius ate bones

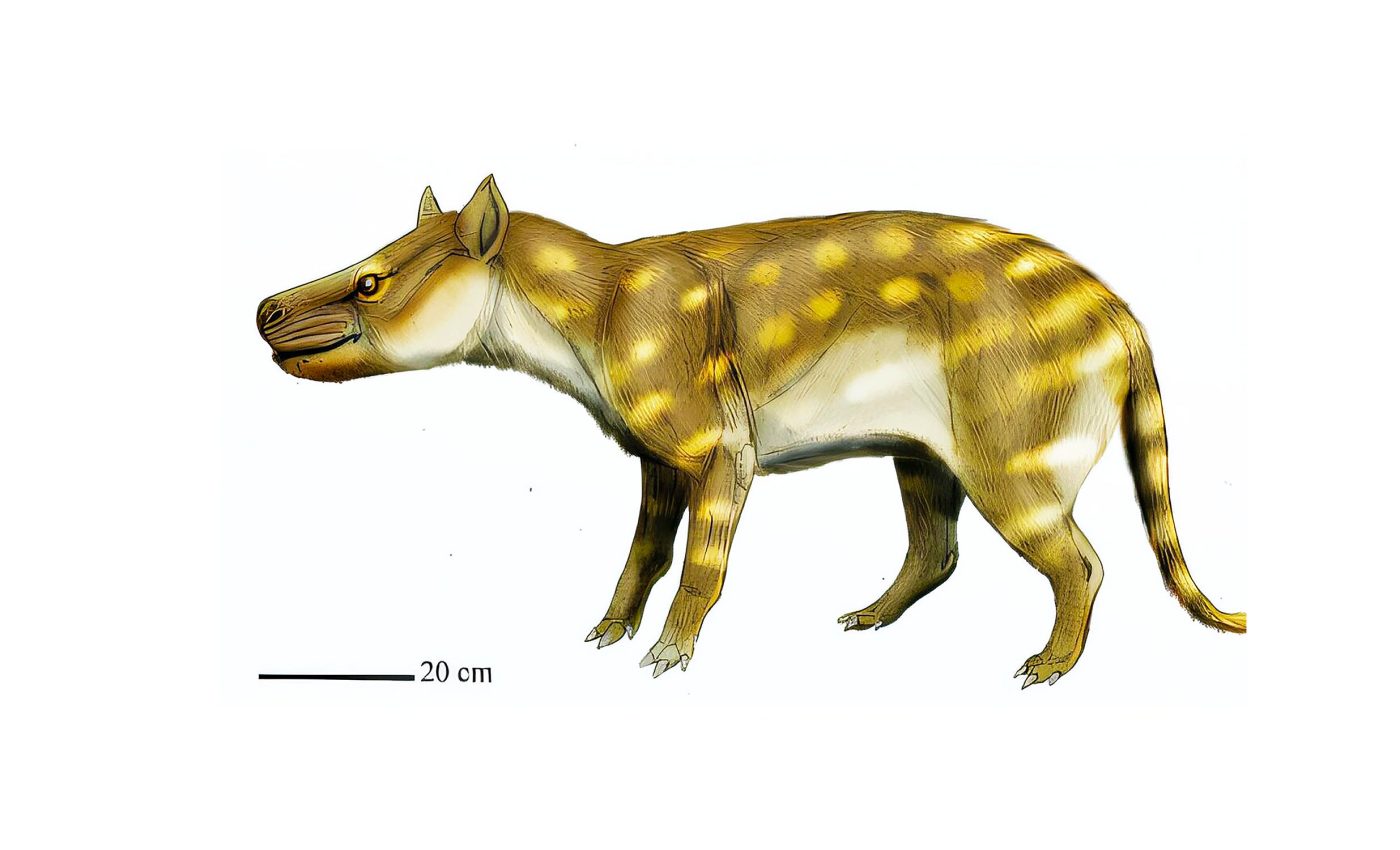

Dissacus praenuntius was roughly the size of a modern coyote and, at first glance, looked like a lanky wolf. But it walked on tiny hooves and belonged to an archaic lineage known as mesonychids.

“They looked superficially like wolves with oversized heads,” Schwartz said, describing them as super weird mammals “Their teeth were kind of like hyenas. But they had little tiny hooves on each of their toes.”

Before the planet heated up, DMTA shows the predator had a diet which resembled that of today’s cheetahs: mostly soft but sinewy meat. Once the PETM began, everything changed.

“We found that their dental microwear looked more like that of lions and hyenas,” Schwartz said. “That suggests they were eating more brittle food, which were probably bones, because their usual prey was smaller or less available.”

The microwear evidence dovetails with other signs of environmental stress. Earlier work has shown many mammal species shrank during the PETM, and Dissacus appears to have followed that trend – smaller bodies need less food.

While scientists once blamed this shrinkage solely on heat, the new findings strengthen the case that limited nutrition was a major driver.

Adaptability drove survival success

“One of the best ways to know what’s going to happen in the future is to look back at the past,” Schwartz said. “How did animals change? How did ecosystems respond?”

For Schwartz, the PETM offers a natural experiment on how warming reshapes food webs. The lesson, he argues, is that dietary flexibility can make or break a species.

“In the short term, it’s great to be the best at what you do,” he said. “But in the long term, it’s risky. Generalists, meaning animals that are good at a lot of things, are more likely to survive when the environment changes.”

That principle is visible today. “We already see this happening,” Schwartz said. “In my earlier research, jackals in Africa started eating more bones and insects over time, probably because of habitat loss and climate stress.”

Pandas, koalas, and other extreme specialists lack that wiggle room and could therefore be more vulnerable as habitats fragment or shift.

Wyoming’s ancient badlands

To trace Dissacus praenuntius through time, the team zeroed in on the Bighorn Basin, one of the rare places where sedimentary layers preserve an almost year-by-year record across the PETM.

Field crews collected dozens of jaws and isolated teeth from successive strata, then scanned their chewing surfaces under high-resolution confocal microscopes.

Sophisticated software converted the textures into numerical values capturing roughness, complexity, and orientation – clues to the animal’s final meals.

Professor Robert Scott, a co-author on the paper, notes that DMTA is revolutionizing paleontology because it captures dietary snapshots just weeks or months before death, unlike isotope analyses that average years.

The method revealed a clear pattern: before the thermal maximum, tooth surfaces carried long, shallow scratches characteristic of slicing flesh; during and after, they showed deeper pits and gouges typical of bone fragmentation.

Dissacus praenuntius faded away

Despite this adaptive flair for bones, Dissacus praenuntius did not make it through the next 15 million years. Bigger, better-equipped carnivores eventually displaced it, and the shifting vegetation of post-PETM North America favored more agile hunters.

Still, its bone-crunching episode underscores how rapidly predators can recalibrate their behavior when climate jolts prey supply.

Schwartz hopes insights like these will aid modern conservation biology by spotlighting which species could be climate winners or losers.

The study also signals the importance of preserving continuous fossil sites: without the Bighorn Basin’s layered rocks, the dietary flip would have remained invisible.

Local fossils, global lessons

Schwartz traces his fascination with fossils to childhood trips along New Jersey’s waterways with his father, an amateur collector. Now close to completing his Ph.D., he is eager to show the broader public how deep time research can illuminate future challenges.

“If I see a kid in a museum looking at a dinosaur, I say, ‘Hey, I’m a paleontologist. You can do this, too.’”

That encouragement matters because, as Earth barrels toward PETM-like CO₂ levels, society will need scientists who can decode past crises to steer us through the next one.

The tale of a jackal-sized mammal gnawing harder fare in a hothouse world is more than a curiosity; it is a mirror held up to our own warming century.

The study is published in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology

Image Credit: ДиБгд, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–