Ants in your yogurt? A long-lost recipe creates a healthier version of this traditional food

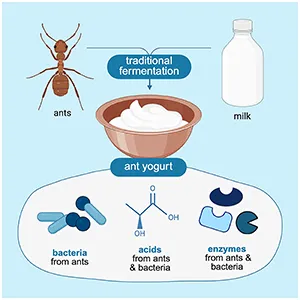

People have been making yogurt for thousands of years, but a team of scientists just brought back one of the most unusual methods ever recorded – a recipe from the Balkans that begins with live forest ants.

The researchers found that these insects carry their own microscopic helpers that can nudge warm milk into becoming yogurt.

Most modern yogurt relies on a dependable pair of bacteria that sour milk and set its gel.

But this new study shows that ants – and the microbes that travel with them – can spark fermentation in a completely different way. The result is a blend of traditional know-how and modern microbiology in a single jar.

Traditional yogurt meets ants

The project was led by Leonie Jahn of the Technical University of Denmark. The team traced a practice remembered across villages in Bulgaria and Turkey, then tested its biological basis in the lab.

They framed the work around the concept of a holobiont, which means an animal together with the microbes that live in and on it.

In this case, the ant and its microbial partners act as one system during fermentation. Today’s yogurts are typically made with just two bacterial strains.

“We dropped four whole ants into a jar of warm milk, following the instructions of Sevgi’s uncle and community members,” said Veronica Sinotte, a microbiologist at the University of Copenhagen.

What ants bring to yogurt

The researchers showed that live ants seeded milk with lactic acid bacteria. This group of microbes turn sugars into acids that help thicken and preserve dairy.

They also contributed formic acid, a defensive chemical in red wood ants that lowers pH. This created a welcoming niche for the acid-loving microbes described in the paper.

The yogurt also carried proteases, which are enzymes that cut milk proteins and tweak texture. The dominant species, Fructilactobacillus sanfranciscensis, is also common in sourdough.

Only live ants built the right community for fermentation under controlled conditions. Frozen or dehydrated ants shifted the mix toward spore-forming species that the authors viewed as undesirable for food.

The chemistry showed a one-two effect. Formic acid from the ants started the pH drop right away, then bacterial metabolism added lactic and acetic acids that pushed thickening further in jars that were incubated and chilled like standard yogurt.

Not your store-bought kind

Conventional yogurt depends on a tight partnership between Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus to sour milk rapidly.

That two-member culture reaches the pH that fully sets milk, around 4.6, and usually does so within a routine fermentation window, as described in the overview already cited.

Ant yogurt behaved differently in side-by-side tests. The authors measured about 2.5 grams per liter of total organic acids in the experimental batches.

That’s compared with up to 12 grams per liter in conventional yogurt, and the pH often stayed between 5.0 and 5.9 while still coagulating.

Their microbiology results helped explain that slower pace. The ant-associated F. sanfranciscensis strain did not metabolize lactose in their assays, so other microbes and enzymes had to carry more of the load.

Consistency also differed. Live ant yogurts showed stable, repeatable bacterial profiles from jar to jar. This indicated that the ants introduced a small but steady set of microbes that took hold under the same conditions.

Use microbes, not ants

The team urged caution. Wild ants can carry a parasite, so in the lab and kitchen they crushed ants into a small aliquot, filtered the slurry through a fine sieve, and then moved only the microbe-rich liquid into warm milk.

They also warned against using frozen or dehydrated ants as a starter. Those methods favored Bacillus species in their trials, organisms that are not welcome in a fresh dairy ferment.

Food safety aside, they emphasized respect for local knowledge and ecology. Red wood ants are part of forest systems, and the point here is to learn from traditional know-how, not to harvest insects casually.

Taken together, the safest translation is not to add ants to milk at home but rather to isolate useful microbes and enzymes in the lab and study how they might help future ferments under controlled and lawful conditions.

Future ferments from nature

Ant yogurt widens the toolbox for fermentation science. Instead of relying on the same two dairy bacteria every time, researchers can scout for new strains that bring different acid profiles and textures.

The sourdough link is more than trivial. A sourdough microbe in milk hints at microbial skills that cross from grains to dairy – and possibly to plant-based milks – where new textures are needed.

This work also spotlights the microbiome, the full set of microbes in a habitat, and shows how an animal’s microbiome can seed food with helpful species.

In traditional dairying that seeding often starts once with nature, then people keep it going by backslopping – adding a spoon of old ferment to new milk.

“I hope people recognize the importance of community and maybe listen a little closer when their grandmother shares a recipe or memory that seems unusual,” said Sinotte.

The study is published in iScience.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–