Deep-sea mining threatens shark species that already face extinction

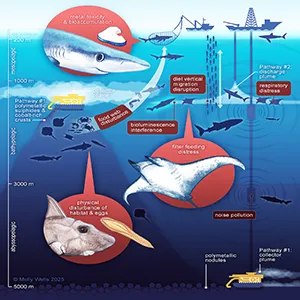

The deep sea feels far away from our daily lives, yet what happens there can change the future of the ocean. Sharks, rays, and ghost sharks live in this hidden realm. These animals are ancient, remarkable, and already under pressure from human activity. Now a new risk is approaching: deep-sea mining.

Scientists from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa warn that thirty species share space with areas being prepared for mining.

Nearly two-thirds of these species are already struggling against extinction. Scraping the seafloor and releasing clouds of sediment into the water could push them even closer to the edge.

“Deep-sea mining is a new potential threat to this group of animals which are both vital in the ocean ecosystem and to human culture and identity,” said Aaron Judah, lead author of the study and graduate student at the UH Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST).

Mining and sharks clash

Judah worked with an international team of scientists. They laid maps of shark, ray, and ghost shark ranges over zones chosen by the International Seabed Authority for future mining. This simple overlay revealed sharp conflicts.

Some species lay eggs directly on the seabed. Mining vehicles rolling across these sites could crush nurseries in seconds.

Others dive through zones where sediment clouds will drift for miles. Feeding and breathing in these waters will not remain the same.

The study considered both the famous and the forgotten. Whale sharks and manta rays appeared on the list.

So did deep-sea residents like the pygmy shark, chocolate skate, and point-nosed chimaera. Each one faces a different kind of danger once the machines arrive.

Alarming results

The results were striking. Thirty species could suffer from sediment plumes. Twenty-five also face disruption from direct seafloor damage.

For seventeen species, mining overlaps more than half of their normal depth range. That scale of overlap suggests impacts will be long-lasting and widespread.

These numbers show that mining does not threaten just a handful of animals. It could change entire ecosystems.

Removing nursery grounds, altering food webs, and shifting predator-prey balances would reshape the deep sea. What happens there rarely stays there.

Spotlight on the Pacific

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone is at the heart of this story. This stretch of ocean floor runs from near Hawai‘i to the eastern Pacific.

Rich in minerals, it has become the main target for mining companies. Yet it also holds habitats that sharks and rays depend on.

“Sharks and their relatives are the second most threatened vertebrate group on the planet, mostly from overfishing,” said Jeff Drazen, senior author and professor of Oceanography at SOEST.

“Because of their vulnerability, they should be considered in ongoing discussions of the environmental risks from deep-sea mining, and those responsible for monitoring their health should be aware that mining could pose an additional risk.”

Sharks already face depleted numbers from fishing. Adding mining to their problems raises the stakes even higher.

Protecting sharks from mining

The researchers argue that conservation must sit at the center of mining plans. They recommend tracking shark and ray populations, including them in environmental assessments, and carving out areas where mining is not allowed.

These ideas could shape new rules under the International Seabed Authority. Companies could also adopt them when they run scientific studies before beginning operations.

These actions sound practical. They could mean the difference between survival and decline for species already struggling to recover. Leaving them out of assessments would ignore a crucial piece of the ocean puzzle.

Impacts may stretch further

Judah explained why these risks do not stop at the mining sites. “Many of the shark species identified in the analysis are highly mobile and can move across wide swaths of ocean,” he said.

“Given their mobility and the proximity of Hawai’i to the areas allocated for mining, impacts in these areas may stretch indirectly to ecosystems near the island chain.”

This mobility connects distant ecosystems. A shark that swims through disturbed waters may later enter areas near Hawai‘i. The disturbance does not remain contained; it spreads, quietly, across the ocean.

More species at risk

Judah is still adding to the picture. His ongoing work tracks species ranges not covered in the first study. With every update, more species could fall into the group already flagged as vulnerable. The scale of risk continues to expand.

Deep-sea mining has been called a frontier, but unlike frontiers of the past, it comes with knowledge of what could be lost.

Sharks, rays, and ghost sharks are not just statistics; they are living evidence of millions of years of evolution.

Choosing whether to mine with care or recklessness will decide if these creatures remain part of the ocean’s story.

The study is published in the journal Current Biology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–