Earth's oceans have officially crossed another crucial planetary boundary

The world’s ocean has moved past a chemical safety line that researchers once hoped it would never reach. A new analysis finds that by about 2020, key ocean acidification metrics had already pushed into the danger zone for marine life, with especially strong changes in the upper 650 feet of water.

That line is part of what scientists call a safe operating space for the planet. Crossing it means a higher risk that ocean ecosystems, and the people who depend on them, will face damage that is hard to reverse.

Ocean acidification boundary

In 2009, researchers proposed the idea of planetary boundaries, global limits that mark a safe operating space for humanity, in a framework that has become central to global sustainability science.

These boundaries cover nine big Earth systems, including climate, biodiversity, fresh water, and the chemistry of the ocean.

The new work was led by Professor Helen S. Findlay, a biological oceanographer at Plymouth Marine Laboratory in the United Kingdom.

Her research focuses on how climate change and acidification reshape marine ecosystems, particularly in the rapidly warming Arctic.

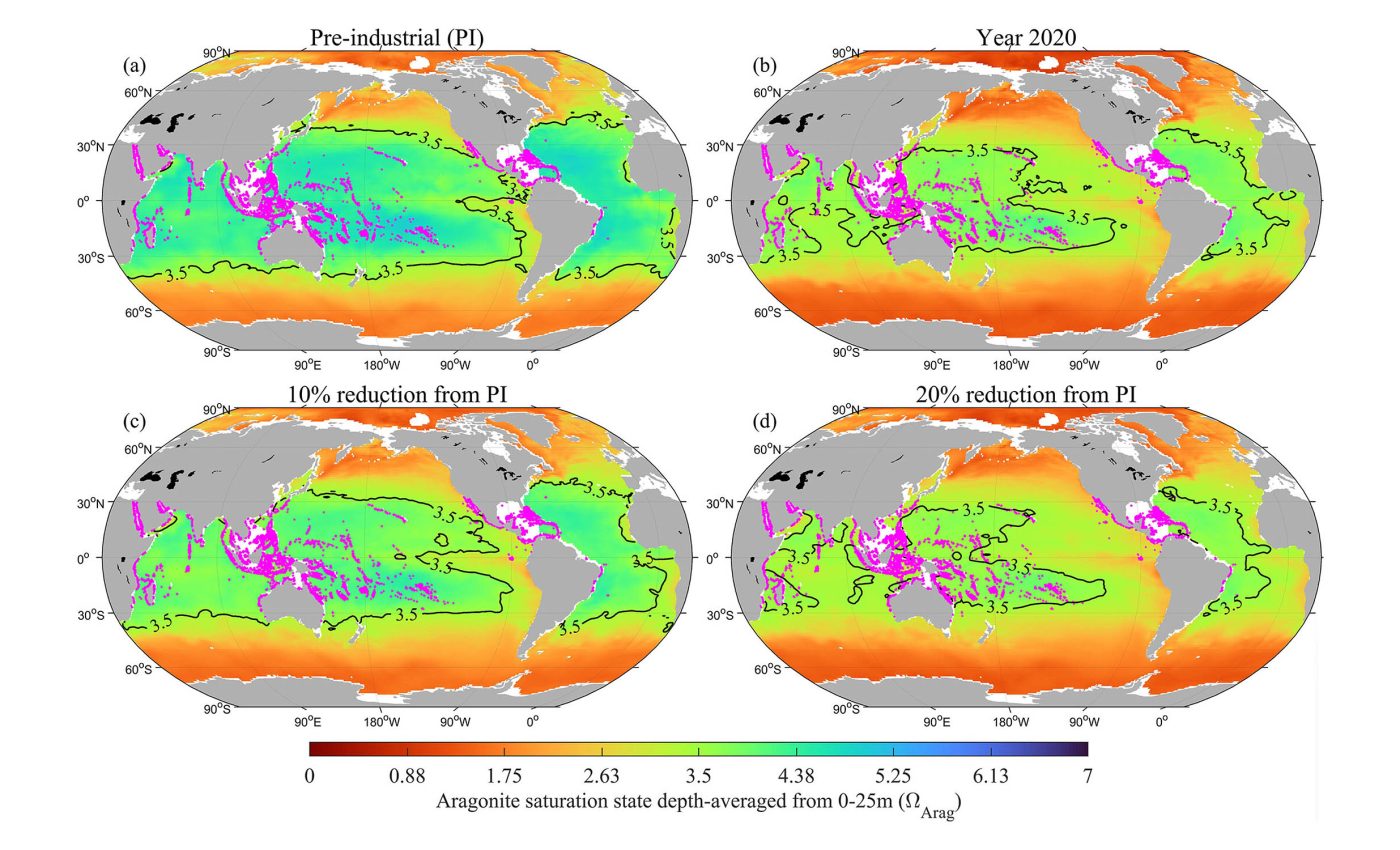

They found that by 2020, ocean chemistry had already crossed into the uncertainty range. Her team estimates that 40 percent of surface waters and 60 percent of water down to 650 feet already lie beyond that level.

Earlier versions of the boundary treated the ocean as one smooth layer at the surface and used a single global benchmark with no uncertainty range.

This updated analysis adds error bars, separates regions, and extends into the subsurface, where most marine organisms actually live and feed.

Chemistry behind the crisis

Scientists use the term ocean acidification, the long term decrease in seawater pH driven mainly by absorbed carbon dioxide, to describe this chemical trend.

The ocean takes up a large share of human carbon emissions, and in doing so quietly changes its own chemistry.

One core measure is aragonite saturation state, a number that shows how easy it is for calcium carbonate shells and skeletons to form and avoid dissolving.

When that value falls, it becomes harder for corals, shellfish, and some plankton to build and maintain their structures.

The original acidification boundary was set at a 20 percent drop in this global saturation state compared with conditions before large scale fossil fuel use.

That limit was supposed to keep polar surface waters from becoming corrosive and to preserve conditions that still support healthy tropical coral reefs.

The new study also highlights how the subsurface ocean, roughly the top 650 feet below the surface, is changing more strongly than the very top layer.

Independent work shows that the analysis of long term data finds the depth where waters become corrosive to aragonite shells has risen by more than 650 feet in some regions since 1800.

Habitats losing safe conditions

These chemical shifts matter most because of what they do to calcifying species, organisms that build hard parts from calcium carbonate and anchor many marine food webs.

As the ocean grows more acidic, suitable habitat for these builders shrinks and fragments.

For warm water coral reefs, the team finds that suitable chemical habitat has already fallen by about 43 percent in tropical and subtropical regions compared with before industrial times.

That loss means less space for the millions of species that use reefs as home, nursery, or hunting ground.

In polar waters, tiny pteropods, small swimming snails that carry fragile aragonite shells, are especially exposed to corrosive conditions.

The analysis suggests their suitable habitat has declined by up to 61 percent, raising concerns for polar food webs that rely on them as prey.

Coastal bivalves such as oysters and mussels show a smaller but still troubling contraction, with about a 13 percent loss of suitable habitat in chemically stressed coastal zones.

A broader review of ocean acidification impacts notes that shellfish fisheries and aquaculture are among the industries most at risk, with knock-on effects for coastal jobs and food security.

What comes next for the ocean

The researchers argue that a boundary based only on a 20 percent global chemical drop is not strict enough to protect key ecosystems.

Their results point to a tighter limit, one based on only a 10 percent decline in average surface saturation state from preindustrial conditions, which would better protect corals, pteropods, and bivalves.

Under that more cautious line, the surface ocean effectively left the safe zone in the 1980s, and by around 2000 the entire surface layer had crossed it.

At the same time, their numbers suggest that more than half of the upper 650 feet now sit in conditions that are marginal or worse for many shell building organisms.

Lessons from ocean acidification

Looking ahead, the fate of this chemical boundary still depends mainly on how fast people cut carbon dioxide emissions.

An IPCC assessment concludes that continued high emissions will drive further acidification, while strong and rapid emission cuts would slow or eventually stabilize these changes.

Acidification also piles on top of ocean warming and falling oxygen levels, creating compound stresses for marine life.

In many regions, species are already dealing with higher temperatures, less oxygen, and more acidic water at the same time, which can make survival limits much tighter than any single stress would suggest.

For people, the message is that the ocean is quietly moving out of its comfort zone even where the surface still looks blue and calm.

Keeping marine ecosystems functional, and keeping food and climate services they provide, will require treating this chemical line in the water as seriously as temperature targets in the air.

The study is published in Global Change Biology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–