Famous 'Wow!' signal received by SETI from deep space was even stronger than once believed

In August 1977, a radio telescope in Ohio that was part of the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI Institute) picked up a brief, powerful radio signal from space that no one has ever been able to explain.

The burst lasted just over a minute, appeared at a highly specific frequency, and was never seen again, yet it looked exactly like the kind of signal scientists hoped might come from beyond Earth.

The astronomer who spotted it circled the strange pattern on a computer printout and scribbled a single word in the margin: “Wow!”

Nearly five decades later, the so-called Wow! signal remains one of the most famous unsolved events in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

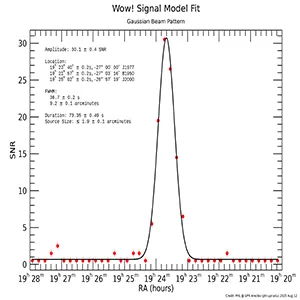

Now, a new reanalysis suggests that the signal was even stronger than scientists originally believed, peaking above 250 Janskys, a measure of radio intensity used in astronomy.

The finding comes from a painstaking effort to recover and digitize original paper records that survived long after the telescope itself was shut down and the site was turned into a golf course.

Reanalyzing old data

The study was led by Abel Mendez at the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo (UPRA), working with scientists and long-time volunteers who preserved the original data.

Their goal was simple but daunting: turn thousands of faded line-printer pages from the 1970s into usable digital measurements.

To do that, the team used optical character recognition software to convert scanned images into readable numbers, then checked the results by hand.

That combination finally allowed modern computers to analyze the signal in detail for the first time.

Importance of the Wow! signal

The original 1977 detection occurred during a survey run by Ohio State University as part of the SETI program.

The telescope recorded a narrowband radio signal that rose and fell smoothly as Earth rotated, matching how a distant cosmic source would appear.

Crucially, the signal did not resemble known human-made interference and appeared near a frequency associated with neutral hydrogen, a key element in the universe.

Because it was strong, isolated, and never repeated, the Wow! signal became a lasting mystery, one that still shapes how scientists think about rare signals from space.

How Big Ear telescope worked

Big Ear Telescope used drift scanning, letting Earth rotate the sky through it, so each spot crossed its view on schedule.

Two feed horns, antenna funnels that collect radio waves, watched the same path about three minutes apart, and the Wow! burst appeared once.

That one-sided detection left two possible sky patches, and it forced later teams to hunt in a wider area.

After Big Ear shut down and the site became a golf course, volunteers saved boxes of printouts for decades.

The team later processed more than 75,000 pages, a scale that made hand-checking impossible and computing essential.

They cleaned scans, trained software on the old typeface, and built scripts that matched each line to time stamps.

Wow! signal frequency fixed

New fits tightened the right ascension, a sky longitude used by astronomers, to two adjacent fields near Sagittarius.

The team also checked declination, a sky latitude measured in degrees, but the old telescope left a broad north-south uncertainty.

Because the horns overlapped differently, both updated coordinates still point to neighboring spots, rather than one exact source.

A mislabeled filter bank, a set of tuned radio channels, flipped the channel order and nudged the signal’s measured frequency.

With that fix, the peak moved to 1420.726 MHz, near the hydrogen line, a natural radio marker of hydrogen gas.

That small change implies a higher radial velocity, motion toward or away from Earth, which trims the list of plausible sources.

Strength of the Wow! signal

The revised flux density, the power received per area and bandwidth, jumped well above earlier estimates for the same one-time burst.

Astronomers report that strength in janskys, a tiny unit used in radio astronomy, to compare signals from very different sources.

That jump matters, because few natural emitters spike so high in such a narrow slice of the radio spectrum.

Patterns against noise

Researchers measured a peak signal-to-noise ratio, how far a signal rises above noise, that stood out from normal background.

Its time profile matched a Gaussian, a bell-shaped curve common in natural data, as the telescope view swept across the sky.

That smooth shape makes random electronics hiccups harder to blame, since many faults smear across frequencies or time.

The authors checked logs and geometry for local interference, and they found no routine transmitter that fits the timing.

Radio astronomers call this radio-frequency interference, unwanted signals from human technology, and they treat it as a daily headache.

They also ruled out a Moon reflection, typical satellites, and major solar activity as drivers for a single-frequency, stationary-looking burst.

Possible natural sources

One leading idea points to neutral-hydrogen, hydrogen atoms with no electric charge, gathered in small cold clouds.

Those clouds can emit narrowband lines, packed into a very small frequency range, that can mimic an artificial tone.

The paper also discusses masers, natural microwave amplifiers in space, as a way to briefly boost that hydrogen emission.

A 2001 search with the Very Large Array listened again and still found nothing at those coordinates.

If the source flared only once, or turned on between horn passes, later scans would miss it every time. Even today, SETI teams face a tough rule: a single detection tells you where to look, not when.

What SETI improved

Modern receivers offer spectral resolution, the ability to separate nearby frequencies, that early surveys could not reach.

They also store raw streams instead of letters on printer paper, which lets later analysts rerun the same night.

Better calibration and cleaner metadata, the notes that explain how data were made, help separate a real signal from a glitch.

Wow! signal remains a mystery

So far, the team fully transcribed only the days around the event, and much of the archive remains unread.

Researchers aim to catalog both obvious repeats and strange one-offs, because the same archive might hide other surprises. Will a recheck of older scans reveal a faint twin of the Wow! burst, or confirm it stands alone?

The authors argue that data can vanish quickly when teams do not archive it, which is why the Big Ear files mattered.

Digital copies let researchers rerun old analysis steps, test alternate assumptions, and explain disagreements about basic numbers.

When teams share cleaned data openly, more eyes can test ideas, spot errors, and squeeze extra value from old observations.

The recalculation does not solve the mystery, but it sets firmer limits on where the burst came from.

By tightening the strength, frequency, and sky position, the new work turns the Wow! signal into a better target.

The study is published in arXiv.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–