Fossil of the first known human face in Europe discovered

Scientists working in a cave in northern Spain have identified the oldest known human face in Western Europe. The partial face belonged to an adult who lived more than one million years ago.

The fossil preserves the left cheek and upper jaw and is dated between 1.1 and 1.4 million years, according to a new 2025 study. It comes from Sima del Elefante, part of the Atapuerca site near Burgos, Spain.

Studying the oldest human face

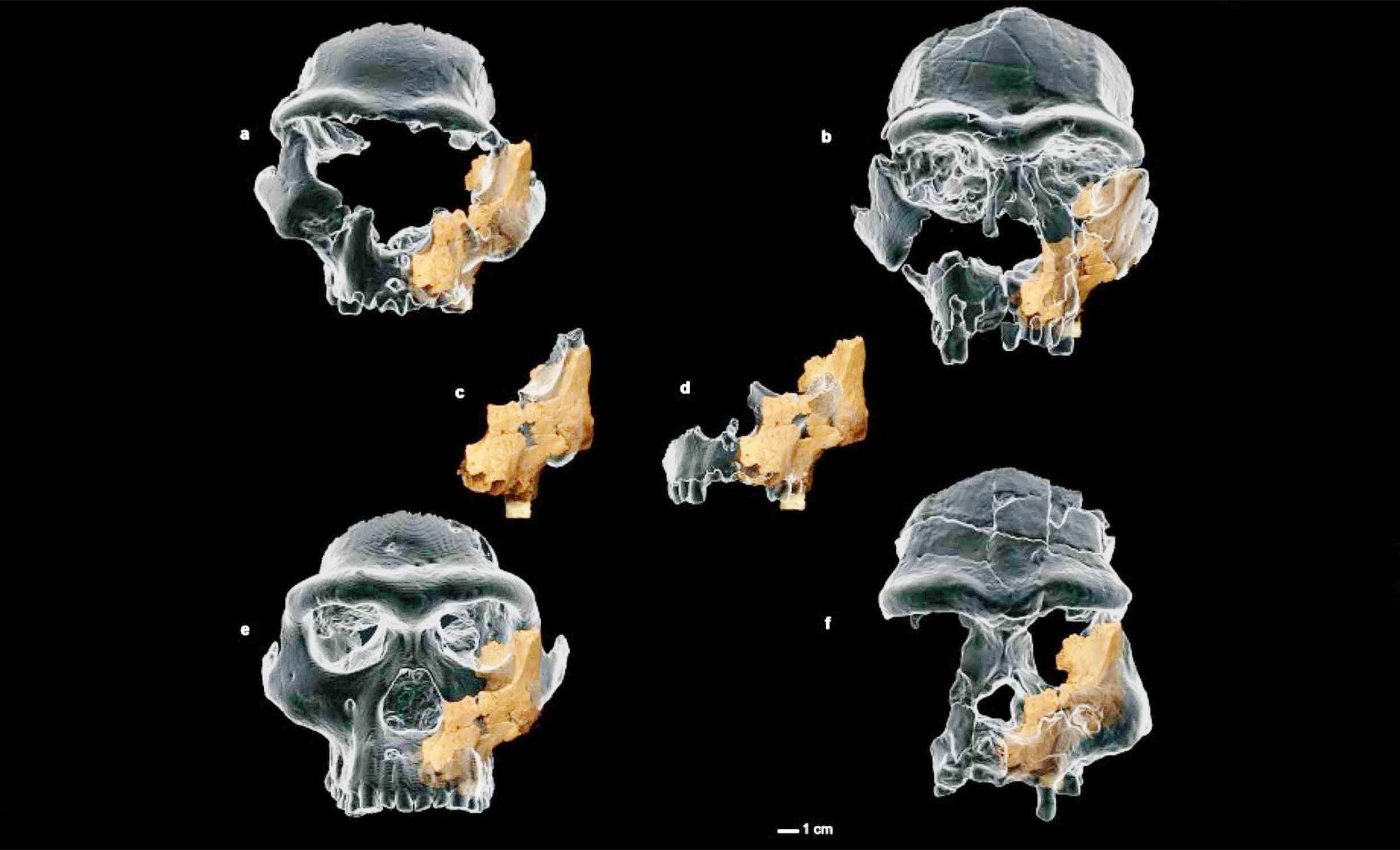

Lead researcher Dr Rosa Huguet of the University Rovira i Virgili (URV) helped uncover and analyze the fossil at Sima del Elefante. Her team rebuilt the fragments using micro computed tomography and careful three dimensional reconstruction.

The preserved maxilla, the upper jaw bone, includes parts of two molars and the left cheekbone. A flat, straight lower rim beneath the eye replaces the curved border seen in some later faces.

Compared with the younger species Homo antecessor from nearby Gran Dolina, this face looks more primitive. The nasal area is flatter, and the midface is narrower than in the Gran Dolina sample.

“These findings open a new line of research in the study of human evolution in Europe,” said Huguet. On that basis, the team assigns the fossil to Homo aff. erectus, which signals a close tie to a known species without a full species label.

New branch or an old traveler?

Early humans reached Eurasia by at least 1.8 million years. That timeline is backed by a complete Dmanisi skull that shows early Homo outside Africa.

In the new fossil, the nasoalveolar region, the area between the nose and upper teeth, is flat and short. That pattern differs from Dmanisi and from later Europeans found nearby.

The midface is also narrow, and the canine hollow is not pronounced. Those traits hint at links to early migrants rather than to later European residents.

Even with these clues, the name is provisional. Researchers need more bones to draw firm lines about species identity.

Life around the cave

The surrounding landscape held humid woodlands threaded by streams. Small mammals, deer, bison, macaques, and hippos left traces in the same layers.

Stone tools of quartz and flint turned up beside animal bones with cut marks. Some cuts on a small rib show careful meat removal with sharp edges.

One molar shows an interproximal groove, a thin wear-channel formed by sliding a sliver between teeth. That habit suggests repeated tooth cleaning or food dislodging over time.

Toolmaking materials likely came from close to the cave. Short visits to butcher animals and shape flakes fit the scattered tools and bones.

Why the timeline shifts

An earlier jaw from the same hillside, recovered at a layer called TE9, dates to about 1.2 million years. That mandible anchors a long human presence at Atapuerca.

A later population at Gran Dolina shows Homo antecessor with a modern looking midface between about 900,000 and 800,000 years. The difference in facial form sets up a clear contrast through time.

A 2023 climate study points to an extreme cold snap near 1.1 million years. Southern Europe may have emptied of people for a time during that cooling.

If populations vanished and later returned, a replacement would make sense. An older group linked to Homo erectus could give way to a later group with different faces.

Lessons from the oldest human face

The team’s reconstruction joins careful fieldwork with micro computed tomography and digital mirroring. Those methods will let future finds snap into place for better comparisons.

As excavations continue, additional cheekbones, noses, or teeth may surface. Each new piece will refine how early Europeans looked and lived.

This face signals that early Europe hosted more than one human line. One line shows ties to Africa and Asia, and another, younger line shows a different facial plan.

The discovery fills a gap in a sparse record without settling every debate. The next seasons at Atapuerca will test the idea of population turnover and timing.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–