Giant spider species that weaves enormous webs has invaded the United States

The bright yellow legs of a giant new spider are catching eyes south of the Mason Dixon line, and experts warn that the Northeast is next in line.

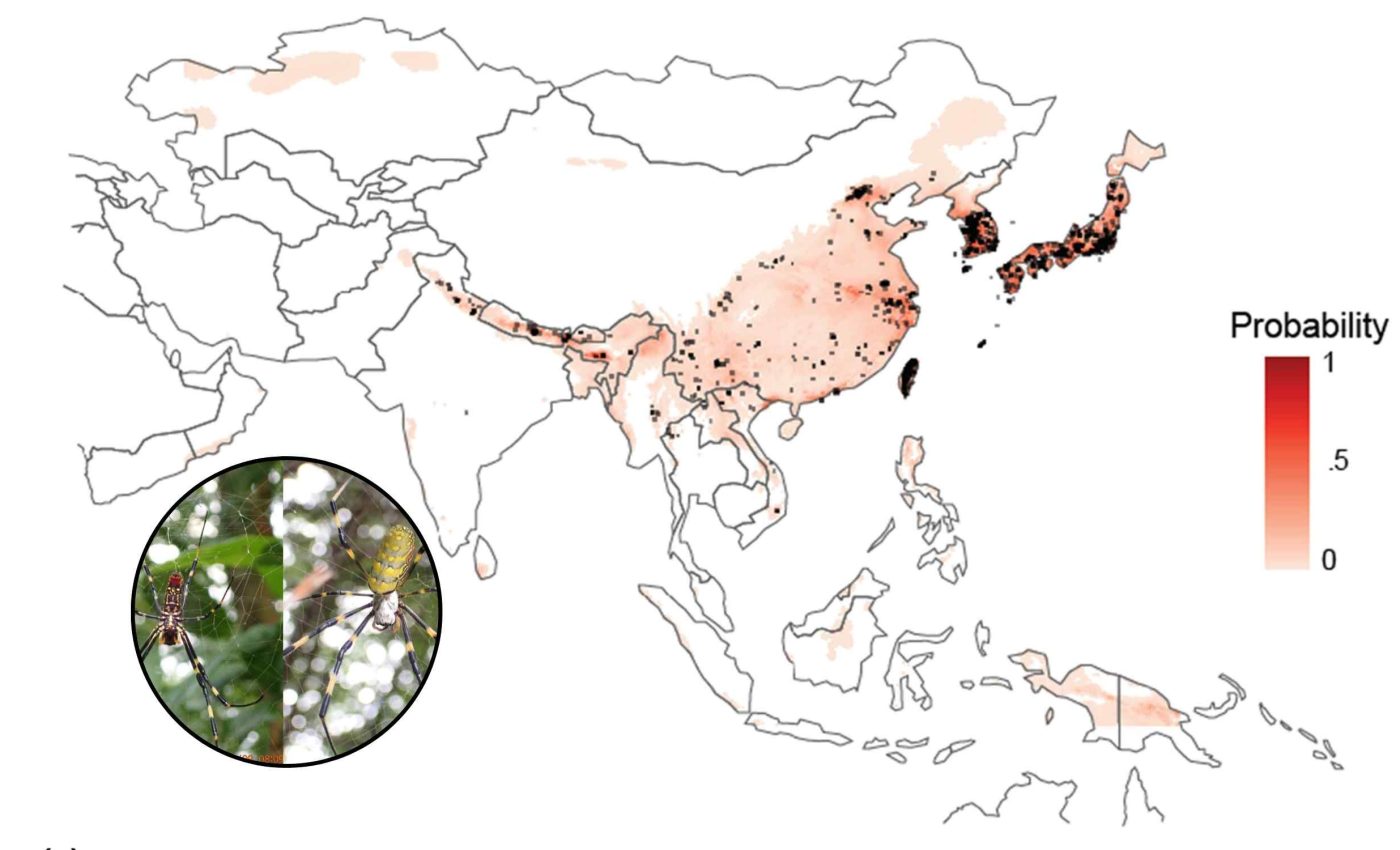

The traveler is the Joro spider, an Asian orb weaver first confirmed in Georgia around 2013. A recent study found that climate matching models show a comfortable fit for this species across most of the eastern United States.

Meet the Joro spider

David Coyle, an invasive species specialist at Clemson University, expects the Joro spider to spread across much of the eastern United States.

As a seasoned arachnologist, he has tracked its rapid expansion from a few Georgia counties to sightings in over a dozen states.

Females span nearly four inches (10 centimeters) tip to tip, and weave gold-tinted webs that can stretch wider than a front door. Males stay thumbnail small and lurk on the edge of the females’ silk, avoiding both predators and courtship missteps.

How the giant spiders got here

Joro spiders likely arrived in the United States by accident, hitching rides in shipping containers, crates, or other imported goods.

Their introduction is believed to have occurred around 2010, but exact records of the first entry point remain unclear due to the nature of global trade.

How they travel on wind currents

Joro hatchlings practice ballooning, releasing gossamer threads that catch air currents and can carry them more than 100 miles (160 kilometers). Older juveniles sometimes hitch rides on cars, mail trucks, and nursery plants, letting human trade fill in the gaps between natural flights.

Their silks are strong enough to remain intact in stiff breezes, so a single breezy afternoon can seed dozens of yards. Because the spiders favor tall launch points, highway light poles and second story decks become unintended takeoff pads.

Cold weather advantage

Joro spiders have shown an impressive ability to handle colder temperatures, continuing to thrive in regions that experience seasonal chills. Their spread into areas with winter lows suggests they can survive brief freezes that would limit other warm-climate species.

In lab trials, three quarters of adult females recovered after being chilled to freezing point for two hours, an endurance unmatched by most orb weavers. That resilience removes the climatic barrier that once boxed warm-weather spiders below Washington, D.C.

New York could see Joro spiders soon

The species is expected to reach the New York metro corridor within the next two to three summers, unless it arrives sooner through accidental transport in cargo. Once established, prevailing wind patterns could allow spiderlings to spread through the Hudson Valley in just one season.

Observations submitted through community science platforms have recorded scattered sightings in northern New Jersey, suggesting the species is beginning to establish itself in the area.

The earliest signs are usually large, gold-colored webs about the size of a basketball, and often stretched between trees or porch railings.

Bigger than they look

A palm sized female looks intimidating, yet her fangs struggle to puncture human skin, and the venom ranks no worse than a bee sting. Most reported bites occur when a spider is trapped against clothing, not during routine yard work.

Joro spiders help trim pest numbers, regularly netting stink bugs, mosquitoes, and even invasive lanternflies in their intricate webs.

Their diets overlap little with pollinating bees, so ecologists do not anticipate major crop impacts.

What to do if one sets up shop

Experts advise leaving non nuisance webs alone; the spiders die off naturally by late November.

If a web blocks a walkway, knock it down with a broom in the evening and the resident often relocates overnight.

Homeowners concerned about numbers can target egg sacs in winter, scraping the cottony bundles into sealed bags for disposal. Commercial pest treatments offer short term relief but will not halt regional spread.

Potential ecological ripples

Surveys in Georgia show sites occupied by Joros support on average fewer native orb weaver species than nearby uninvaded spots. Researchers suspect competition for web space is the main driver, though long-term studies are still under way.

The spiders’ large silk mats may also alter insect flow, rerouting prey away from smaller web builders. Whether that shift cascades through local food webs remains uncertain, making continued monitoring a priority.

Looking ahead

States from Pennsylvania to Maine are updating invasive species watch lists to include the Joro spider, aiming to standardize reporting. Citizen uploads with clear photos remain the fastest way to confirm the giant spider’s arrival in new counties and to guide research crews.

No eradication plan exists, so adaptation will be key as the arachnid advances. Public outreach stresses calm coexistence, reminding residents that a startling spider is still an ally against biting pests.

The study is published in Ecology and Evolution. Photo credit: David R. Nelsen.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–