Study shows gray hair could be a sign of good cellular health, not a reason to stress

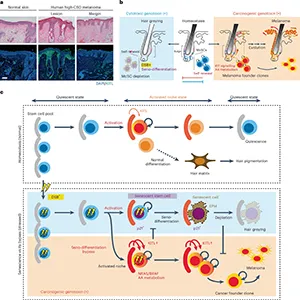

Hair color reflects how a small group of cells works, rests, and responds to stress. Those cells sit in the hair follicle and refill the supply of pigment-makers every time a strand grows again.

When that system fails, hair can turn gray, or in other cases, damaged cells can linger and become cancerous.

The path these cells take depends on the kind of stress they encounter and the signals they hear from nearby tissue.

Scientists study this decision-making process because it connects everyday aging with cancer biology. Hair follicles cycle through phases of growth and rest throughout life.

Understanding what tips the balance of those cycles helps explain why color fades with age and how tumors can start in the same pigment lineage.

Scientists from The University of Tokyo have found that one stem cell type can age safely or turn cancerous, depending on the stress it faces. The same decision that fades color can also feed disease.

Cancer link to gray hair

The cells that keep color pigment forming create a reservoir, often described as “helper” cells. These are called melanocyte stem cells, and they live in a specialized corner of the hair follicle known as the niche.

Their job is simple on paper: replace pigment-producing cells during each growth cycle. In practice, it involves constant quality control because skin faces many sources of DNA damage.

Over time, tiny cracks form in the cells’ DNA – caused by sunlight, chemical exposure, or simply the everyday wear and tear of life.

Once that damage builds up, the cells must choose what to do next. It can protect the body by aging and stepping aside – or ignore the signal and risk turning rogue.

DNA stress and graying

The new study, led by Professor Emi Nishimura and Professor Yasuaki Mohri, tracked how these stem cells react under pressure. The team studied mice using long-term lineage tracing and gene expression tools.

When the cells suffered double-strand breaks in their DNA, they stopped renewing. Instead, they matured too soon in a process called senescence-coupled differentiation, or seno-differentiation.

That decision ends their role as stem cells. The pigment-making line shuts down, and the hair loses color. The process runs under the p53-p21 pathway, a molecular signal that acts like a switch for damage control.

The body sacrifices the damaged cells for the sake of safety, leaving behind gray strands as evidence.

When protection fails

The story shifts when the stress comes from carcinogens such as ultraviolet B radiation. The same cells act differently.

Even with DNA damage, they skip the protective path. Nearby tissue sends KIT ligand signals that block the p53-p21 response. Instead of aging, the cells start dividing again, expanding in clusters.

What once ensured color now turns risky. Those expanding cells can set the stage for melanoma, a dangerous form of skin cancer. The contrast is striking: one type of damage triggers safe aging, another drives dangerous growth.

Gray hair or cancer?

“These findings reveal that the same stem cell population can follow antagonistic fates – exhaustion or expansion – depending on the type of stress and microenvironmental signals,” said Professor Nishimura.

“It reframes hair graying and melanoma not as unrelated events, but as divergent outcomes of stem cell stress responses.”

Her words capture the core of the discovery. Graying hair is not a random sign of age; it is a result of the body choosing caution. Cancer appears when that caution disappears.

The same stem cell, under different signals, becomes either a quiet survivor or a silent threat.

The body’s signal system

Seno-differentiation looks like a built-in safety plan. When a cell senses danger, it stops multiplying. That act protects the tissue from turning malignant.

But when outside factors block that response, damaged cells survive longer than they should. Those survivors can mutate, form tumors, and spread.

The researchers make one point clear: having gray hair does not prevent cancer. Both graying and melanoma grow from the same cellular stress but follow opposite directions. It is the body’s internal signal system that decides who wins.

Future study of cancer’s gray hair link

Two practical directions follow from the results. One is to support the protective differentiation program when DNA damage is severe, so damaged stem cells exit instead of renewing.

The other is to block the niche signals that prevent that exit, such as pathways linked to arachidonic acid metabolites or excessive KIT ligand activity.

By nudging the microenvironment, future therapies could tilt outcomes toward safety without chasing cosmetic goals.

Between repair and risk

By revealing how stem cells choose between shutting down or expanding, the study bridges the biology of aging and cancer.

The research shows that aging is not only decay but a strategy – one that removes damaged cells before they harm the body. Cancer begins when that cleanup fails.

This idea also supports the importance of “senolysis,” the natural removal of worn-out cells. When the body clears out its tired or broken parts, it lowers the chance of disease. The balance between regeneration and restraint keeps tissues healthy over time.

Every gray hair may reflect a moment of cellular decision-making. The same logic that paints our hair can, under stress, turn into a threat.

The research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and the Japan Agency for Medical Research.

The study is published in the journal Nature Cell Biology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–