Scientists finally learn how muscles rebuild and repair themselves

Every workout leaves tiny scars inside your muscles, yet they rarely fail you the next day. Instead, those tissues quietly rebuild themselves, using an internal repair crew that starts working within hours.

A new line of research shows that this repair crew includes thousands of nuclei that rearrange inside each muscle fiber to help restore damage.

Experiments with mice and humans track this movement in real time and show how it rebuilds broken sections from within.

How muscles repair everyday damage

That moving crew has come into focus thanks to work led by William Roman, a cell biologist at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona.

His research, now continued in Australia, asks how muscle cells coordinate repair and communication along their entire length.

Skeletal muscle powers movement and posture, but every contraction puts stress on the thin outer membrane of each fiber.

Small rips or holes can let calcium rush in, disturb protein structure, and weaken the fiber if nothing responds quickly.

For large injuries, the body eventually recruits satellite cells, muscle stem cells that fuse with damaged fibers or form new ones.

Everyday exertion usually creates much smaller lesions, so the existing fiber leans on its own muscle repair tools rather than waiting for new cells.

Muscle repair system is unusual

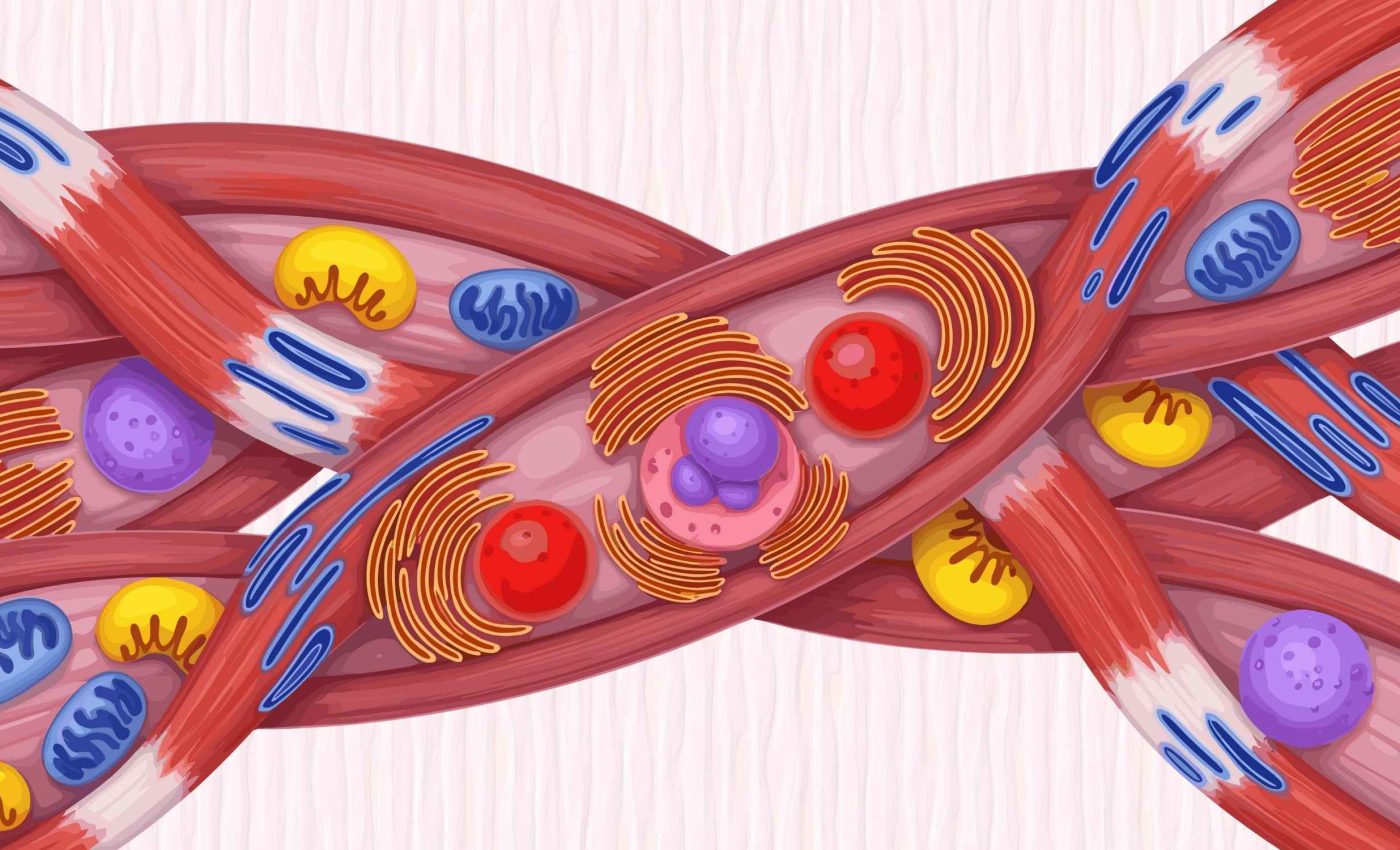

Most cells carry a single nucleus, but myofibers, long muscle cells packed with contractile machinery, can stretch for millimeters. To keep such large cells under control, they pack in thousands of nuclei so each region has local oversight.

In mouse muscle, one commentary estimates five to ten nuclei in every four thousandths of an inch (0.1 millimeter) of fiber length.

Most of those nuclei sit near the fiber’s outer edge, clustered between the membrane and the stack of contractile units inside.

For years, many biologists assumed these nuclei settled into fixed positions once a muscle matured. But high-resolution videos now show that they can move toward damaged zones over the course of a few hours.

Nuclei on the move

In one carefully designed study, Roman and colleagues used treadmill exercise and targeted laser damage to create tiny tears in muscle fibers.

Using fluorescent markers and time lapse imaging, they tracked nuclear positions and saw them cluster around each injured site within several hours.

Those traveling nuclei, known as myonuclei, form the mobile command centers in the process of muscle repair. They do not float freely within a muscle fibre cell, but move along an internal scaffold that gives each cell a built in transport system.

Muscle repair and cellular scaffolding

That scaffold is made of microtubules – stiff protein tubes that act like tracks inside cells – and motor proteins that walk along them.

When calcium surges in at the lesion, signaling cascades reorganize these structures so motors such as dynein pull myonuclei toward the wounded zone.

Once myonuclei gather around a tear, they start producing extra messenger RNA, short lived genetic messages that guide protein building.

Those messages travel to nearby ribosomes, which assemble new structural and repair proteins right where the fiber is damaged.

“Our experiments with muscle cells in the laboratory showed that the movement of nuclei to injury sites resulted in local delivery of mRNA molecules,” said Roman.

Local muscle repair advantages

Classical textbooks describe muscle regeneration as a slow process driven mainly by satellite cells that divide, mature, and merge with existing fibers.

Roman’s experiments showed that many of the tiny tears they induced resealed and rebuilt while satellite cells stayed on the sidelines.

That idea fits with a review showing that myonuclear position and gene activity change over days as fibers recover.

Together, these findings sketch a picture in which the muscle fiber’s own nuclei can repair many everyday problems long before stem cells arrive.

An explainer on muscle repair notes that pairing stem cell treatments with strategies that support myonuclear mobility could offer more complete recovery.

Researchers now wonder whether training programs or future drugs might strengthen this built-in system in people with frail or diseased muscle.

Energy, aging, and resilience

All of this rapid movement and protein production demands large amounts of energy at the injury site. Nearby mitochondria – cell structures that act as tiny power plants – supply that energy and also help buffer surges of calcium.

An overview of muscle aging concludes that when mitochondria falter, both muscle stem cells and fibers struggle to regenerate fully after injury.

That link suggests that supporting mitochondrial health could indirectly keep the nuclear repair crew working at top speed in older adults.

Future therapies might not only add new cells but also protect existing nuclei and mitochondria so they coordinate repairs more efficiently.

In that scenario, exercise, diet, and targeted drugs could all become tools for tuning the same internal network, rather than working through separate pathways.

More questions need answers

Even with these discoveries, scientists still know surprisingly little about how myonuclei decide where to go and which genes to turn on.

Various groups now track nuclear movements and gene responses with advanced imaging and sequencing, but many of the key decision points are still hidden.

One influential paper argues that each myonucleus governs a flexible territory inside the fiber rather than a fixed domain.

In that view, moving nuclei toward a lesion reshapes those territories so protein production focuses exactly where the structure has failed.

Taken together, the new work suggests that muscles are not simply wearing out as we age or train but constantly rebuilding themselves from within.

“Even in physiological conditions, regeneration is vital for muscle to endure the mechanical stress of contraction,” said Roman.

The study is published in Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–