Gold mining is destroying the Amazon rainforest from within

The Amazon should heal when the digging stops, yet many regions stripped of trees to clear a path for gold mining remain barren. The missing ingredient is not just nutrients, it is water that the land can no longer hold.

A new study shows that small scale gold mining reshapes the ground so that rain rushes away and heat builds at the surface.

The result is soil that cannot keep moisture where roots need it, so plantings fail and natural regrowth stalls.

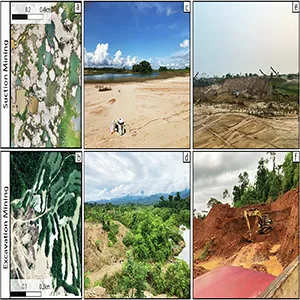

Gold mine scars in the Amazon

Lead author Abra Atwood of the Woodwell Climate Research Center (WCRC) led the work with collaborators in Peru and the United States, combining field instruments, drones, and subsurface imaging.

In Peru’s Madre de Dios region, years of artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) have left tailings and ponds in place of forest.

A long-term analysis recorded about 370 square miles of forest loss to gold mining there between 1985 and 2017, with most of the increase in the last decade of that period.

The team focused on suction mining, a method that uses high pressure water to blast and slurp sediment toward sluices. This process strips the topsoil, piles sand into mounds, and leaves pits that fill as ponds.

On the mounds, water shoots through the coarse sand at roughly 48 feet per day compared with about 0.24 feet per day in nearby primary forest soil, so upper layers dry fast.

Surface temperatures on the bare sand can climb near 140 F, which stresses seedlings before they ever establish leaves or shade.

Water evaporates from the soil

To see what sits below the ground, the researchers ran electrical resistivity imaging (ERI), a technique that maps how easily current moves through underground layers as a proxy for moisture.

The ERI profiles revealed a dry, highly resistive layer of sand down to about 5 to 6 feet, perched above wetter material.

They then measured hydraulic conductivity, which is how quickly water moves through soil. Mining sands showed values orders of magnitude higher than forest soils, confirming that water drains away from the root zone before plants can use it.

The driest, hottest spots were the tall tailings far from the water table, where roots would have to travel deeper to find moisture.

Sites near pond edges or lower in the terrain were cooler and wetter, and those were the only places where spontaneous regrowth showed up.

“It’s like trying to grow a tree in an oven,” said Josh West, professor of Earth sciences and environmental studies at USC Dornsife.

“When roots can’t find water and surface temperatures are scorching, even replanted seedlings just die,” said Atwood.

Repairing Amazon forests after gold mining

Standard reforestation recipes focus on nutrients and species lists, but in this setting the bottleneck is water access in the top few feet.

The study’s most practical advice is to lower the height of sand mounds and backfill the ponds, which shortens the path to groundwater and evens out moisture.

There is a second benefit to filling ponds. A separate study shows that artificial lakes created by mining can convert mercury from the gold process into methylmercury, a more bioavailable neurotoxin that builds up in fish and people.

Sites near existing water, such as low ground beside ponds, are the best early candidates for restoration plantings because moisture is stable and temperatures are modest.

Exposed tailings far from water are poor bets until heavy earthmoving reduces their height and increases soil water retention.

The data also hint at a sequence. First, regrade to bring roots closer to water. Next, plant hardy pioneer trees that can handle heat and poor structure while slowly building organic matter at the surface.

What the instruments actually said

Sensors buried in Amazon sand near gold mines recorded sharp swings in soil moisture after rain, then rapid drying rates, while forest soils changed more slowly over days to weeks.

Drone mounted thermal cameras confirmed that barren surfaces ran hotter than nearby canopy or the strips right next to water.

ERI profiles consistently showed that mined sands form a dry lid that blocks seedlings from tapping deeper moisture unless they are close to a pond or a low swale. That pattern lined up with the only patches of natural regrowth found in the survey.

Gold, Amazon trees, and the future

Across the broader Amazon, mining’s footprint on forest loss is larger than once assumed.

One research effort that tracked Brazil’s mines and their surrounding roads, work camps, and transport hubs tied roughly 9 percent of Amazon deforestation between 2005 and 2015 to mining related activity.

Those indirect effects matter because they keep opening new edges where heat and wind reduce humidity, and where dry soils compound the stress already caused by lost shade and shallow roots.

When land is reworked into hot, dry hills of sand above deep ponds, the physics of flow and heat leave little room for trees to restart a forest.

The most direct fix is to reshape the land so that water stays near the surface long enough for roots to reach it.

That is why the authors stress moving sand, filling holes, and using water access to rank sites for planting, because those steps actually address the limiting factor that their measurements uncovered.

The study is published in Communications Earth & Environment.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–