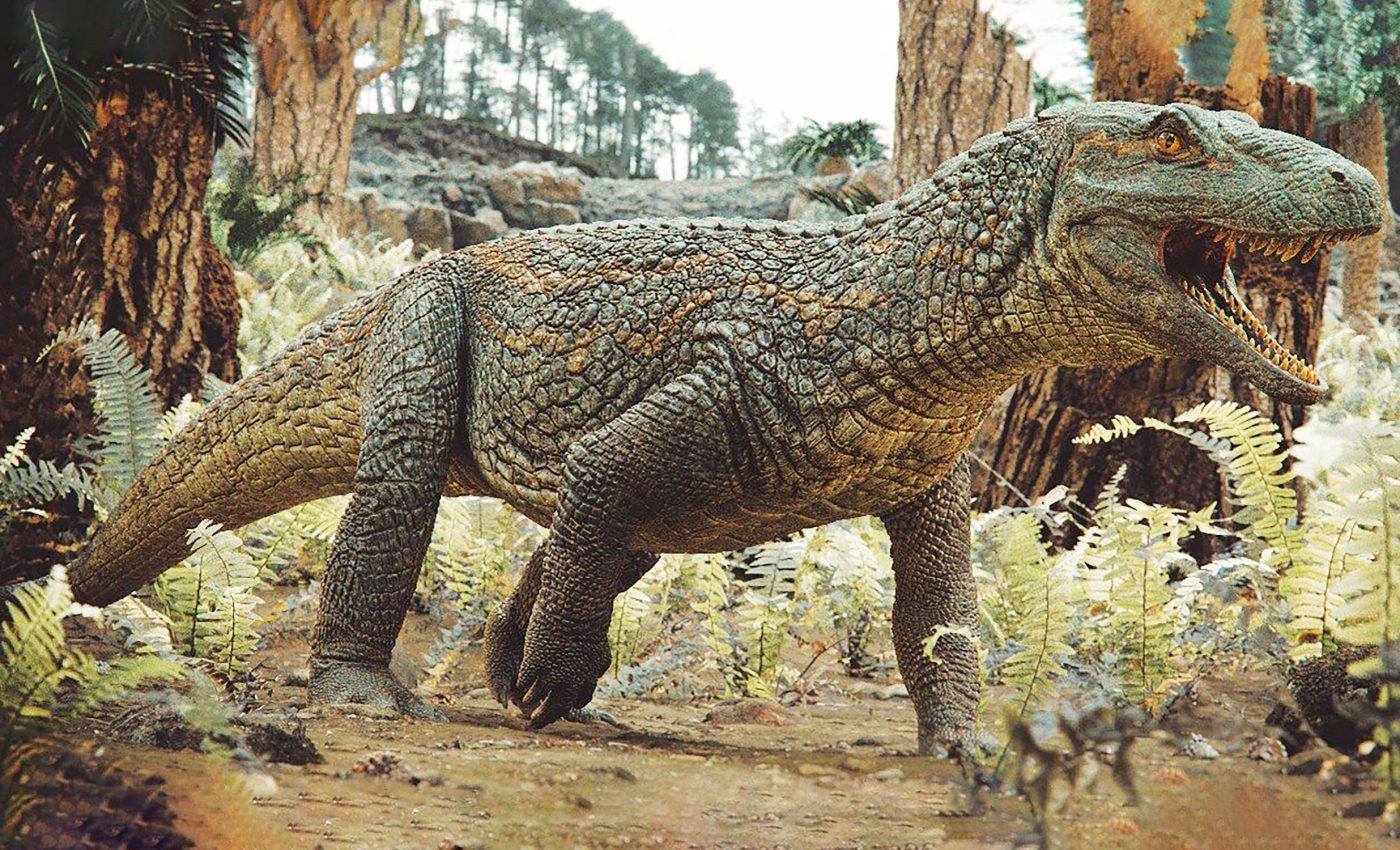

Long before dinosaurs, this fierce crocodile ancestor dominated Earth

A newly described carnivorous reptile from southern Brazil is the kind of animal most people would casually label a dinosaur – but it isn’t. Tainrakuasuchus bellator belongs to Pseudosuchia, the ancient lineage that ultimately gave rise to today’s crocodiles and alligators.

The beast prowled the Triassic some 240 million years ago, just before dinosaurs rose to dominance.

Covered with armored plates and built for quick strikes, it adds a fierce new character to a crowded cast of early archosaur predators.

Body that evolved for hunting

Roughly 7.9 feet long and about 132 pounds in mass, Tainrakuasuchus bellator had a long, agile neck and a slim snout packed with sharp teeth.

That profile points to a precision hunter – one capable of sudden lunges, quick head snaps, and a locking bite to hold onto struggling prey before it could get away.

Bony skin plates, known as osteoderms, armored its back, echoing the body plan of modern crocodiles. Despite the superficial dinosaur vibe, its hip and femur joints mark it squarely as a pseudosuchian, not a dinosaur.

“This animal was an active predator, but despite its relatively large size, it was far from the largest hunter of its time,” said lead author Rodrigo Temp Müller from the Universidade Federal de Santa Maria.

“Although its appearance superficially resembles that of a dinosaur, Tainrakuasuchus bellator does not belong to that group.”

One of the clearest distinctions from dinosaurs appears in its pelvis, where the hip and femur joints differ sharply.

Tainrakuasuchus was built for speed

Anatomy suggests a predator built for speed and control rather than bone-crushing power. The long neck, light jaw, and recurved teeth are classic tools for seizing and holding mobile prey.

Although the fossils do not preserve limbs, the team infers a four-footed stance that provided stability and maneuverability for ambushes and quick pivots.

In its Triassic ecosystem, Tainrakuasuchus bellator would have overlapped with much larger pseudosuchians. It carved out a niche among multiple top and mid-level predators with different body sizes and hunting styles.

According to Müller, the discovery of Tainrakuasuchus bellator represents the complexity of the ecosystem at the time, with different pseudosuchia species – varying in sizes and hunting strategies – occupying specific ecological niches.

“Its discovery helps illuminate a key moment in the history of life, the period that preceded the rise of the dinosaurs.”

A previously unknown species

The partial skeleton – lower jaw fragments, parts of the vertebral column, and pieces of the pelvic girdle – turned up in May 2025 near Dona Francisca in Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil.

Careful lab preparation freed the bones from their surrounding rock, revealing distinctive features that didn’t match any known species.

“Despite the diversity of pseudosuchians, they remain poorly understood, as fossils of some of their lineages are extremely rare in the fossil record,” Müller said.

“The fossils we found underwent a meticulous preparation process in the laboratory, during which the surrounding rock was carefully removed.”

“Once the anatomical details were revealed, we were delighted and really excited to reveal the specimen represented a species previously unknown to science.”

South America and Africa links

The genus name blends Guarani and Greek. Tainrakuasuchus combines tain (“tooth”) and rakua (“pointed”) with suchus (“crocodile”), a nod to those recurved, gripping teeth.

The species epithet, bellator – Latin for “warrior” or “fighter” – honors the people of Rio Grande do Sul. It symbolizes their strength, resilience, and fighting spirit amid recent devastating floods.

Comparisons link Tainrakuasuchus to Mandasuchus tanyauchen from Tanzania. The South America–Africa connection makes sense for the Triassic because the continents formed Pangaea and animals could disperse across land that is now oceanic.

“This connection between animals from South America and Africa can be understood in light of the Triassic Period’s paleogeography,” said Müller.

“At that time, the continents were still united, which allowed the free dispersal of organisms across regions that are now separated by oceans. As a result, the faunas of Brazil and Africa shared several common elements.”

Lessons from Tainrakuasuchus bellator

The team places Tainrakuasuchus bellator on the margins of a vast arid desert. It’s essentially the same environmental backdrop in which the earliest dinosaurs began to appear.

In southern Brazil at that time, reptiles had already diversified into multiple ecological roles, from giant apex predators to fast-moving mid-sized hunters.

“Tainrakuasuchus bellator would have lived in a region bordering a vast, arid desert – the same setting as where the first dinosaurs emerged,” Müller said.

“It shows that, in what is now southern Brazil, reptiles had already formed diverse communities adapted to various survival strategies.”

Every new pseudosuchian helps fill a sparse fossil record. It also refines the picture of who ruled the food webs just before dinosaurs took over.

Tainrakuasuchus bellator illustrates how complex Triassic ecosystems already were. It also shows how easily we can misread their actors through a dinosaur-shaped lens.

Here, the “warrior” turns out to be croc kin. It is sleek, armored, and perfectly tuned for swift, surgical hunts in a harsh landscape.

The study is published in the Journal of Systematic Paleontology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–