Mars' icy past may be key to surviving future missions

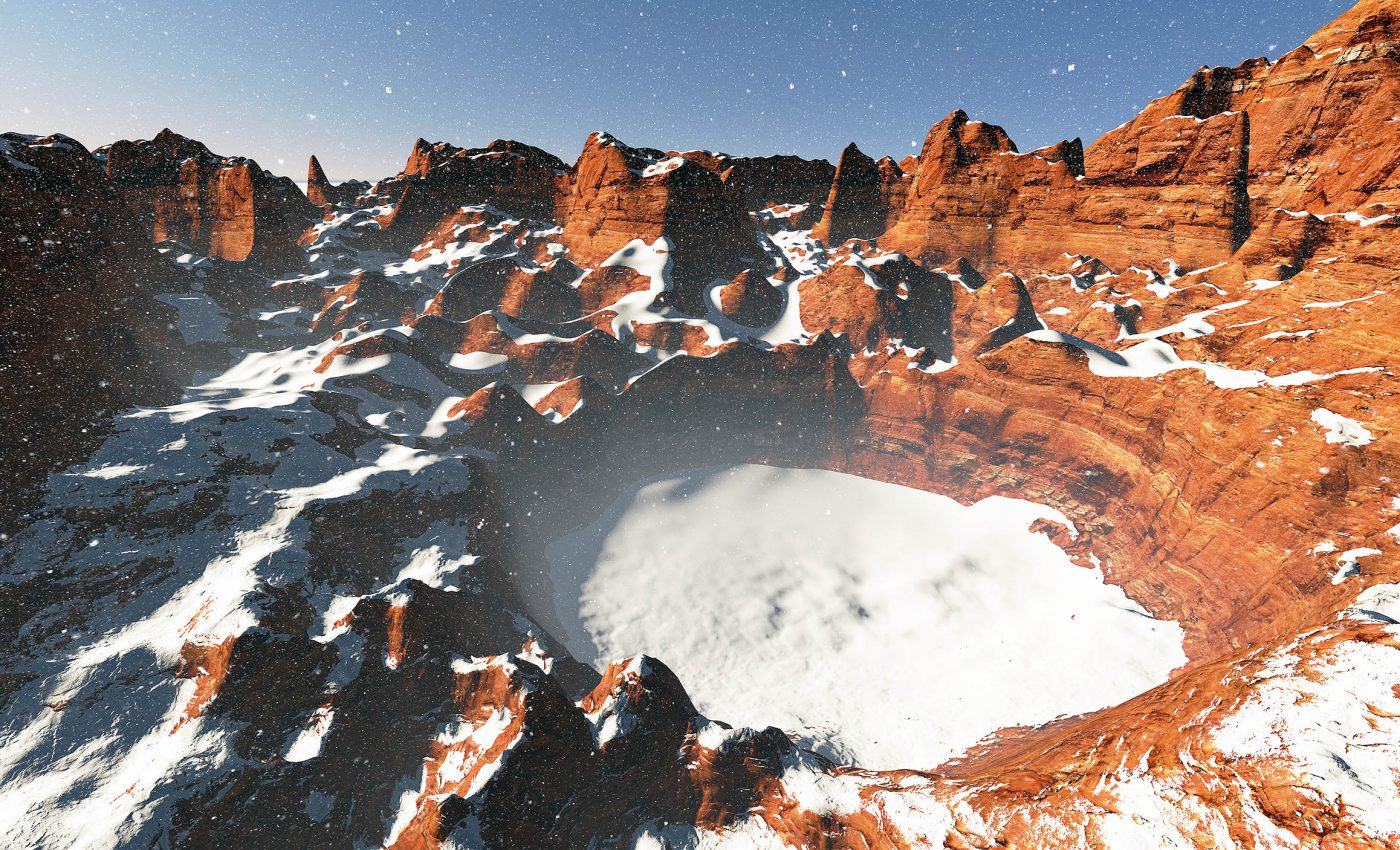

Mars wasn’t always the bone-dry world we see today. A new study reveals the Red Planet experienced a series of ice ages, much like Earth, but with a twist.

Instead of regaining water with each cycle, Mars steadily lost it. And now, clues trapped in ancient craters are revealing just how that happened.

Researchers have uncovered patterns of glaciation across Mars’ surface that stretch back hundreds of millions of years.

Using high-resolution images, they’ve spotted landforms shaped by glaciers–ridges, debris piles, and cracked, maze-like surfaces in craters between 20° and 45° north latitude. These frozen features are telling a story of a once-saturated planet that slowly dried up.

Mars craters filled with ancient ice

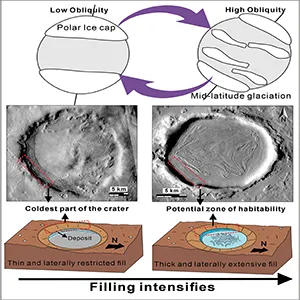

The researchers focused on how ice behaved over long timescales. On Mars, the steep, shadowy walls inside these craters act like natural freezers, helping water ice persist instead of melting away.

During several ice ages, scientists have found that ice has repeatedly formed on the colder, southwest-facing walls, some of it dating back as far as 640 million years, with the most recent occurrence around 98 million years ago.

But each time the planet froze again, there was less water than before. The glaciers shrank. The features left behind, like moraines, which are piles of debris dropped by retreating glaciers, got smaller.

This pattern shows Mars wasn’t just going through regular climate changes. It was drying out.

Mars’ tilt drives ice ages

Unlike Earth, Mars has a wobbly axis. Its tilt can shift wildly over millions of years, changing how sunlight hits different parts of the planet. These changes drive ice ages by shifting ice where it can survive.

During colder periods, ice creeps down from the poles into lower latitudes, collecting in craters. But with each cycle, less ice returns, indicating that the water may have escaped into space or sunk underground.

The study was led by Dr. Trishit Ruj from the Institute for Planetary Materials at Okayama University.

“Mars went through repeated ice ages, but the amount of ice deposited in craters steadily shrank over time. These icy ‘time capsules’ not only reveal how Mars lost its water but also mark places where future explorers might tap into hidden ice resources,” said Dr. Ruj.

Buried ice = water and supplies

Ice isn’t just a clue to Mars’ past, it’s a key to its future. Any crewed mission to Mars will need water to stay hydrated, but bringing it from Earth is expensive and unrealistic for long-term stays.

That’s where buried ice becomes critical. It can be used for drinking, split into hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel, and even provides breathable air.

“Knowledge of long-lived ice deposits helps identify safe and resource-rich regions for future robotic and crewed landings,” said Professor Tomohiro Usui from the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (SAS).

In other words, craters with ancient glacial deposits might be the best spots for future Martian bases. They offer natural shelters with built-in water supplies.

Hidden water sources on Earth

The study doesn’t just teach us about Mars. It also sharpens tools we use to track Earth’s climate. The same technology used to study Mars’ frozen craters can help monitor glaciers, permafrost, and hidden water sources on Earth.

“By tracing how Mars stored and lost its ice, this study guides future explorers to water supplies and offers insights that can be applied to Earth’s changing environment,” the researchers noted.

“Mars serves as a natural laboratory for understanding how ice behaves over vast timescales. The insights we gain here can sharpen our understanding of climate processes on Earth as well,” added Dr. Hitoshi Hasegawa from Kochi University.

Ice for future Mars explorers

Mars arid environment did not happen overnight. It lost its water slowly, throughout ice ages that came and went.

With each cycle, water that formed into ice dissipated; the Red Planet retained less and less of what it had.

Those craters scattered across its surface? They’re more than just old impact sites. They’re holding onto the last signs of a colder, wetter Mars, and maybe the tools future mission explorers will need to stay alive.

The full study was published in the journal Geology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–