Mars orbiter pinpoints the current path of mysterious interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS

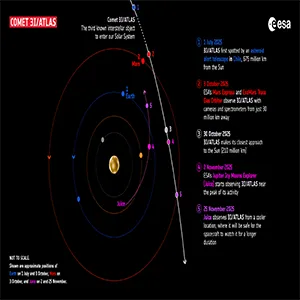

On July 1, 2025, astronomers spotted a faint new comet and labeled it 3I/ATLAS. It wasn’t just another icy rock. It turned out to be just the third known interstellar object that humans have ever tracked moving through our Solar System.

Teams around the world rushed to predict where it would go next, because a visitor from outside our stellar neighborhood usually does not stay for long.

This comet is on a one-way journey. It is cutting through our system, swinging around the Sun once, then heading back out into deep space.

If scientists want to understand what it is made of and how it behaves, they have to know exactly where it will be and when.

Chasing comet 31/ATLAS

3I/ATLAS is not cruising slowly. Because this comet is passing through our Solar System fast, travelling with speeds up to about 155,000 mph (250 000 km/h), it will soon vanish into interstellar space, never to return. A rock moving that fast covers the distance from Earth to the Moon in less than a couple of hours.

To get useful data, telescopes and spacecraft have to point at just the right spot ahead of the comet, not where it has already been.

With a reliable trajectory in hand, astronomers can aim their instruments with confidence and squeeze as much science as possible out of this brief encounter.

Views from Mars orbit

For a while, all the tracking came from observatories on Earth. Until September, figuring out the location and trajectory of 3I/ATLAS relied on Earth-based telescopes.

Then, between October 1 and October 7, a spacecraft orbiting Mars joined the effort and changed the picture in a big way.

The European Space Agency (ESA) used its ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, a spacecraft that usually studies the martian atmosphere, to watch the comet as it passed by.

The comet passed relatively close to Mars, approaching to about 18 million miles (29 million km) during its closest phase on October 3.

The Mars probe got about ten times closer to 3I/ATLAS than telescopes on Earth, and it observed the comet from a new viewing angle.

The triangulation of its data with data from Earth helped to make the comet’s predicted path much more accurate.

While the scientists initially anticipated a modest improvement, the result was an impressive ten-fold leap in accuracy, which significantly reduced the uncertainty of the object’s location.

Using a Mars orbiter in a new way

This was not a routine job for the Mars mission team. It was a challenge to use the Mars orbiter’s data to refine an interstellar comet’s path through space.

The CaSSIS instrument was designed to point towards the nearby martian surface and look at it in high resolution. This time, the camera was aimed at the skies above Mars to catch the tiny, distant 3I/ATLAS comet sweeping by across a starry backdrop.

Plotting the path of comet 3I/ATLAS

The astronomers in the planetary defence team at ESA’s Near-Earth Object Coordination Centre (NEOCC), who are used to determining the trajectories of asteroids and comets, had to account for the spacecraft’s special location.

Usually, trajectory observations are made from fixed observatories on Earth, and occasionally from a spacecraft in near-Earth orbit, like the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope or NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope.

The astronomers are well-practiced in considering their location as they determine the future locations of objects, called ephemeris.

This time, the ephemeris of 3I/ATLAS, and in particular the prediction’s precision, depended on accounting for the exact location of the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter that is in fast orbit around Mars.

It required working together in a combined effort by several ESA teams and partners, from flight dynamics to science and instrument teams.

Challenges and subtleties that are usually negligible had to be tackled to reduce error margins as much as possible, in order to achieve the highest accuracy possible.

The resulting data on comet 3I/ATLAS marks the first time that astrometric measurements, made from a spacecraft orbiting another planet, have been officially submitted and accepted into the Minor Planet Center (MPC) database.

The database acts as a central clearing house for asteroid and comet observations, streamlining data collected by different telescopes, radar stations and spacecraft.

Small “rehearsal” for real threats

Even though 3I/ATLAS poses no threat, it was a valuable exercise for planetary defense.

ESA routinely monitors near-Earth asteroids and comets, calculating orbits to provide warnings if required.

As this “rehearsal” with 3I/ATLAS shows, it can be useful to triangulate data from Earth with observations from a second location in space. A spacecraft may also happen to be closer to an object, adding even more value.

Practicing with spacecraft data beyond Earth orbit hones important skills. It also demonstrates the value of leveraging resources that were not designed for asteroid detection, to boost readiness in case of a threat.

The more ways scientists learn to track tricky objects, the better prepared they will be if, one day, a dangerous body threatens to cross Earth’s path.

New missions watching the sky

ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) is also observing 3I/ATLAS just after its closest approach to the Sun, when the comet is in a more active state.

We don’t expect to receive data from Juice’s observations until February 2026. Those observations will help fill in how the comet behaves as sunlight heats its surface and drives out gas and dust.

ESA is also preparing the Neomir mission, to cover the known blind spot that the Sun causes for asteroid observations, its bright glow outshining the faint glimmer of an asteroid or comet.

Neomir will be located between the Sun and Earth to detect near-Earth objects coming from the Sun’s direction at least three weeks in advance of potential Earth impact. That kind of early warning is crucial if humanity ever needs to act.

Lessons from comet 3I/ATLAS

Icy wanderers such as 3I/ATLAS offer a rare, tangible connection to the broader galaxy. To actually visit one would connect humankind with the Universe on a far greater scale.

ESA is preparing the Comet Interceptor mission that will learn more about a comet – with luck, it just might be an interstellar one.

Each new object like 3I/ATLAS shows that our Solar System is not isolated. With smarter tracking, flexible spacecraft, and missions designed to react quickly, scientists are getting ready for whatever comes racing in next from the space between the stars.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–