Massive valleys, cracks, and canyons are frozen in time on Mars

Back in April, images from Mars revealed the eastern end of the Acheron Fossae region – a striking mix of rugged cliffs, smooth plains, ancient craters, and frozen lava. Now, attention shifts to the west, where the land tells a different chapter of the same story.

Here, deep cracks run for hundreds of miles. Valleys wind their way across the surface. Channels twist like lazy rivers – only these rivers have never carried water. Instead, they’ve been shaped by slow-moving ice and rock.

The western Acheron Fossae isn’t just a place of geological variety. It’s a record of Mars’ restless past, preserved in the textures and layers of its landscape.

Mars’ cracked landscape

Scientists at Freie Universität Berlin, who processed data from Mars Express’s High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC), have been examining these features in detail.

The region has long fascinated researchers – in fact, one of the first images ever released from the HRSC in April 2004 explored this very terrain, just months after Mars Express began orbiting the Red Planet.

Acheron Fossae is what scientists call a “horst and graben” system – alternating high and low blocks of land formed when the crust stretches and fractures.

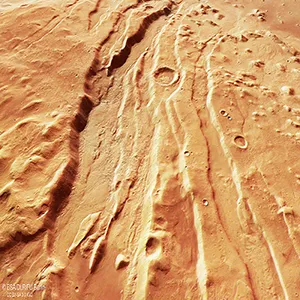

“This pattern can be seen most clearly in the prominent channels slicing vertically through the frame just right of center,” noted the research team.

These features likely date back more than 3.7 billion years, to a time when Mars’s interior was still churning with heat.

Rising molten rock forced the surface apart, creating cracks and valleys more than 0.6 miles deep that still define the region today.

Ice, not water, fills the valleys

Once these valleys formed, they kept changing. From above, the valley floors look smooth, traced by delicate curves that mimic a river’s path.

But instead of flowing water, these channels hold “a slow, viscous flow of ice-rich rock, a lot like the rock glaciers we see here on Earth.”

Rock glaciers respond quickly to changes in climate, making them a kind of natural time capsule. In Acheron Fossae, they reveal a history of alternating cold and warmer periods – repeated cycles of freezing and thawing.

The cause? Mars’s wild axial tilt. Unlike Earth, whose tilt stays relatively stable thanks to the Moon, Mars leans at different angles over time. These shifts drive extreme climate swings.

“Mars’ tilt has swung between 15 and 45 degrees in the last 10 million years, while Earth’s has varied between 22 and 24.5 degrees,” noted the researchers.

These cycles, called Milankovitch cycles, influence both planets’ climates, but their impact is far more dramatic on Mars.

Eroded layer of Acheron Fossae

Moving east across the landscape, the deep cracks of the fossae fade into flat, dark plains. Between them lies a band of small hills and mesas – the leftovers of a rock layer that once covered the area.

Over time, ice and rock flows wore it down, leaving “rounded hills (knobs) and flat-topped plateaus (mesas) interspersed with narrow, meandering channels.”

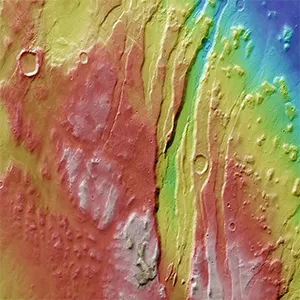

A topographic view makes this change easy to see: red and yellow highlands shift into pale and dark blues marking the lowlands.

Off to one side, another smooth plain sits quietly, not far – in planetary terms – from Olympus Mons, the Solar System’s largest volcano, located about 750 miles (1,200 kilometers) away.

Future research on Acheron Fossae

Since 2003, Mars Express has been mapping the planet in color, in three dimensions, and at resolutions never achieved before.

Over two decades of work have transformed how we see Mars – and regions like Acheron Fossae are a perfect example of why that matters.

Studying this fractured, icy terrain isn’t just about piecing together the planet’s past. It also helps prepare for the future.

The valleys here hold frozen water mixed with rock – a resource that could one day support missions landing nearby.

Knowing how that ice formed, and how it changes with Mars’ shifting climate, could help planners decide where to send landers or even crews.

Acheron Fossae also acts as a climate archive. Its ice layers may hold clues about when Mars lost its thick atmosphere, how long it stayed warm enough for liquid water, and whether traces of ancient microbial life could still be hidden within the frozen ground.

Remote and rugged, this landscape might end up being more than just a snapshot of the past – it could be a guide to Mars’ future, and to where humans set foot next.

Image credit: ESA/DLR/FU (G. Neukum)

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–