Miniature tools were South China’s ancient strategy for survival

Small stone tools in South China reflect a history of adaptation. A new analysis shows that people repeatedly chose small, portable designs as climates shifted and groups moved.

The scale is large for archaeology. A team examined more than 12,000 artifacts from three sites in Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guangdong to map how toolmaking changed between roughly 18,000 and 5,600 years ago.

This study is the most detailed look so far at miniaturized stone technologies in the region.

Three ways to make small tools

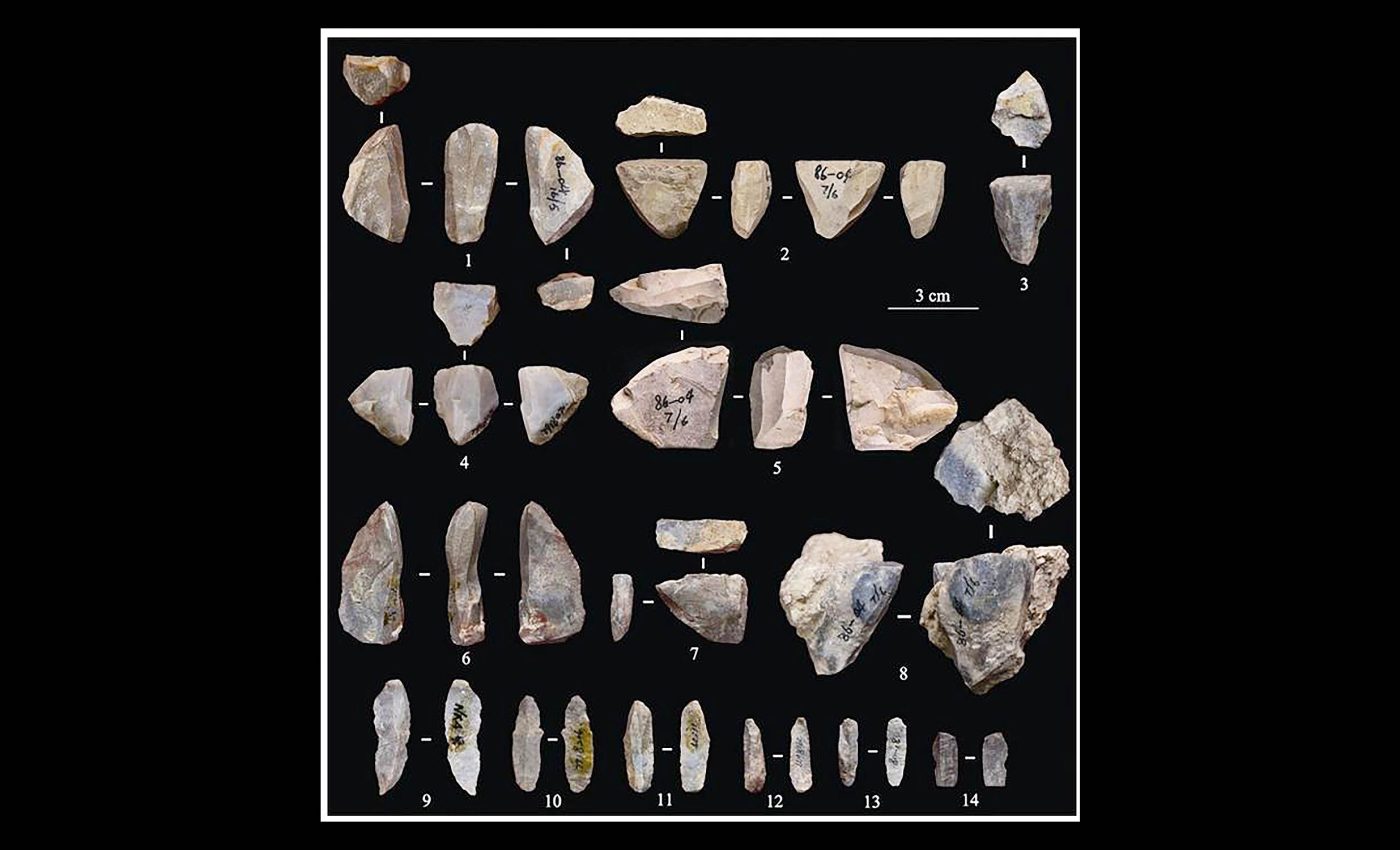

The researchers identified three distinct ways to make small tools, including bipolar splinters, bladelet-like pieces, and standardized microblades that grew more elongated over time.

They also found the artifacts form clear statistical clusters, which suggests deliberate design choices rather than random flaking.

The study draws South China into East Asia’s broader discussion of miniaturization, which has long been focused on northern regions.

It also reframes lithic (stone artifact) variability as a flexible response to stress and mobility rather than a single cultural template.

The project highlights a single lead voice for readers. It was led by Shixia Yang at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), with collaborators in Australia and the United States.

Three toolkits, one big idea

At Fodongdi in tropical Yunnan, the team recorded 456 small splinters made by striking quartz pebbles on an anvil.

This method corresponds to the Last Glacial Maximum – the cold peak about 20,000 years ago, when resources were tighter and mobility likely higher.

Fulin, near the high eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, shows 222 tiny bladelet-like flakes. They date to around the Younger Dryas, a sudden return to near-glacial conditions between 12,900 and 11,700 years ago.

These pieces would have given hunters efficient cutting edges that packed and traveled easily in rough country.

Xiqiaoshan in Guangdong preserves 387 highly standardized microblades made from wedge-shaped and conical cores during the middle Holocene.

Small tools became longer

The assemblage points to refined production sequences and possible input from northern groups. It also tracks a shift toward longer, slimmer forms that maximize edge per mass.

That local pattern matches prior analyses of Xiqiaoshan core methods, which detail platform preparation and repetitive blade removal from wedge-shaped cores. That background supports the new microblade findings.

Testing tool design versus chance

To separate intentional design from chance breakage in South China’s stone assemblages, the authors used principal component analysis (PCA), a statistical tool that reduces many measurements into a few key dimensions.

This approach shows each site’s toolkit occupies its own shape space, which argues for different goals and constraints.

They also applied k-means clustering to group artifacts by shared traits, without forcing categories in advance.

The clusters map cleanly onto toolmaking strategies observed under the microscope, which reinforces the interpretation that these are coherent technological systems.

The power of small tools

Miniaturized toolkits save raw material, extend cutting life per weight, and fit easily into pockets and packs. Those advantages matter when people face patchy resources or have to move often across steep terrain.

The Fodongdi splinters also show a specific method known as dual-impact reduction. This is a way to strike small pebbles between a hammer and anvil to coax out thin, sharp pieces from tough stone.

The technique is simple, repeatable, and uses raw materials efficiently when large nodules are rare.

Linking North and South

For years, microblade industries have been more visible in northern China and Northeast Asia than in the south.

A detailed review outlines wedge-shaped cores and their spread across northern regions and beyond.

The new South China dataset helps fill that gap by showing similar, small-tool logics emerging under different ecological pressures.

It also suggests that contact between regions, and not just local invention, shaped how people made and used stone.

Context shapes conclusions

Some of the artifacts come from older excavations and curated collections rather than fresh digs, which can limit strict control over context.

That does not erase the patterns, but it urges caution when linking tools to specific, short-term events in South China.

Analysts also face equifinality since different processes can produce similar outcomes.

A thin flake might be a deliberate bladelet or just a by-product, so the combination of metric patterns and close technological analysis is essential.

Small tool adaptation across ages

Climate whiplash is not new. Seeing how past communities balanced mobility, material limits, and risk sharpens our sense of human flexibility without romanticizing it as an easy fix.

“Our findings demonstrate that lithic miniaturization in South China was not a marginal phenomenon but a central adaptive strategy,” said Yang.

The line captures the heart of the project without overstating what stone alone can prove.

The record spans the Holocene, the warm interval of the last 11,700 years, and the tail end of the Pleistocene before it.

Across that span the South China sites track a clear drift toward longer, slimmer pieces that carry more edge for the weight.

That trend, together with the site-specific strategies, points to a shared design logic that people tuned to in different places and under different pressures.

It is a precise kind of convergence, one that turns small chips into a big signal about how humans persist.

The study is published in the Journal of Geographical Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–