Fossil discovery of a 'wonder reptile' rewrites the history of evolution

Hair and feathers transformed the way animals lived – providing insulation, enabling flight, and offering a means of display. In birds and mammals, these features are known to arise from complex genetic programs.

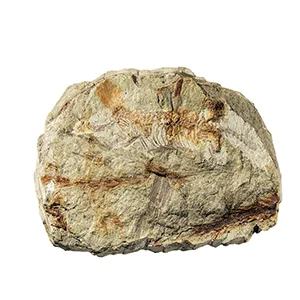

Reptiles, however, were believed to lack such sophisticated structures. That view is now being challenged. A remarkable fossil from the Middle Triassic reveals a small, tree-dwelling reptile adorned with a tall, feather-like crest.

Named Mirasaura grauvogeli, this creature lived about 247 million years ago. It had a slender bird-like skull, a long tail, and a striking dorsal display.

New fossils from France show that Mirasaura’s skin structures weren’t just decorative. They evolved from a genetic toolkit present in early amniotes, well before feathers or hair ever appeared.

Mirasaura had odd skin

Two nearly complete skeletons and over 80 isolated skin fragments reveal an upright crest of overlapping appendages.

These are not feathers, but they resemble them in form. Each appendage had a narrow central ridge and two distinct curved layers on either side.

Unlike bird feathers, Mirasaura’s structures didn’t branch into barbs. Instead, they formed continuous surfaces with delicate ridges, or rugae, along their lengths.

SEM scans show these features were not stiff scales. Their flexible, wrinkled texture suggests they bent easily, maybe to catch light or motion.

“The fact that we have discovered such complex skin appendages in such an ancient group of reptiles sheds a new light on their evolution,” said Dr. Stephan Spiekman, a postdoctoral researcher at Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart.

Beautiful Mirasaura crest was for show

The skull was just 17 millimeters long and had large, forward-facing eyes. These features suggest excellent depth perception that is useful for a life in trees. The snout was mostly toothless and likely helped it pick insects out of bark.

Mirasaura’s body was long and barrel-shaped. Its limbs were adapted for grasping, and its claws were large and curved. It was agile, able to cling to branches much like a monkey.

The crest sat right above a noticeable hump in the spine. This area may have supported the upright posture of the appendages, giving Mirasaura its showy backline. Researchers rule out flight or insulation. Instead, the crest likely played a role in display.

“Mirasaura grauvogeli shows us how surprising evolution can be and what potential it holds,” said Professor Rainer Schoch.

Feather-like pigments

Some preserved tissue on the crest contains fossilized melanosomes. These tiny pigment carriers resemble those found in bird feathers, not in reptile scales or mammal hair. Analysis shows a wide variety in shape, common in feathers, rare in scaly skin.

“The melanosomes found in Mirasaura soft tissues are more similar in shape to those found in extant and fossil feathers than melanosomes found in mammalian hair and reptilian skin,” noted Dr. Valentina Rossi.

This could mean Mirasaura displayed some form of coloration, perhaps even patterns for mating or recognition. Still, no color has been confirmed.

A reptile with a similar crest

The only other reptile with a similar dorsal crest is Longisquama insignis, another Triassic diapsid. Like Mirasaura, it had long, midline skin appendages. The two are now confirmed to be close relatives in the group Drepanosauromorpha.

The similarities between their crests, including bilateral symmetry, a central axis, and consistent patterning, suggest a shared origin.

Still, their appendages are not feathers. They evolved separately, shaped by similar genetic programs but on different paths.

Mirasaura rewrites reptile family tree

Mirasaura pushes back the origin of Drepanosauromorpha by nearly 20 million years. These reptiles, previously known only from the Late Triassic, now have roots in the early Middle Triassic.

Phylogenetic analysis places Mirasaura outside the major modern reptile lineages. It lived before lizards, crocodiles, or birds. It was not part of Sauria, the group that includes all living reptiles. This makes its advanced skin structures even more surprising.

‘Mirasaura provides the first direct evidence that such structures actually did form early on in reptile evolution, in groups not closely related to birds and extinct dinosaurs,’ said Dr. Spiekman.

Skin evolution in reptiles

Louis Grauvogel collected fossils in Alsace starting in the 1930s. Among them were pieces of Mirasaura, though no one recognized them at the time.

In 2019, the Grauvogel family donated the collection to the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart. There, researchers uncovered this unexpected gem.

The name Mirasaura grauvogeli means “Grauvogel’s wonder reptile.” This ancient climber, with its feather-like crest, changes what we know about skin evolution in reptiles. It shows that nature can invent similar solutions in distant lineages, again and again.

The study is published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–