NASA reveals why Mars changed from a blue world into a red desert

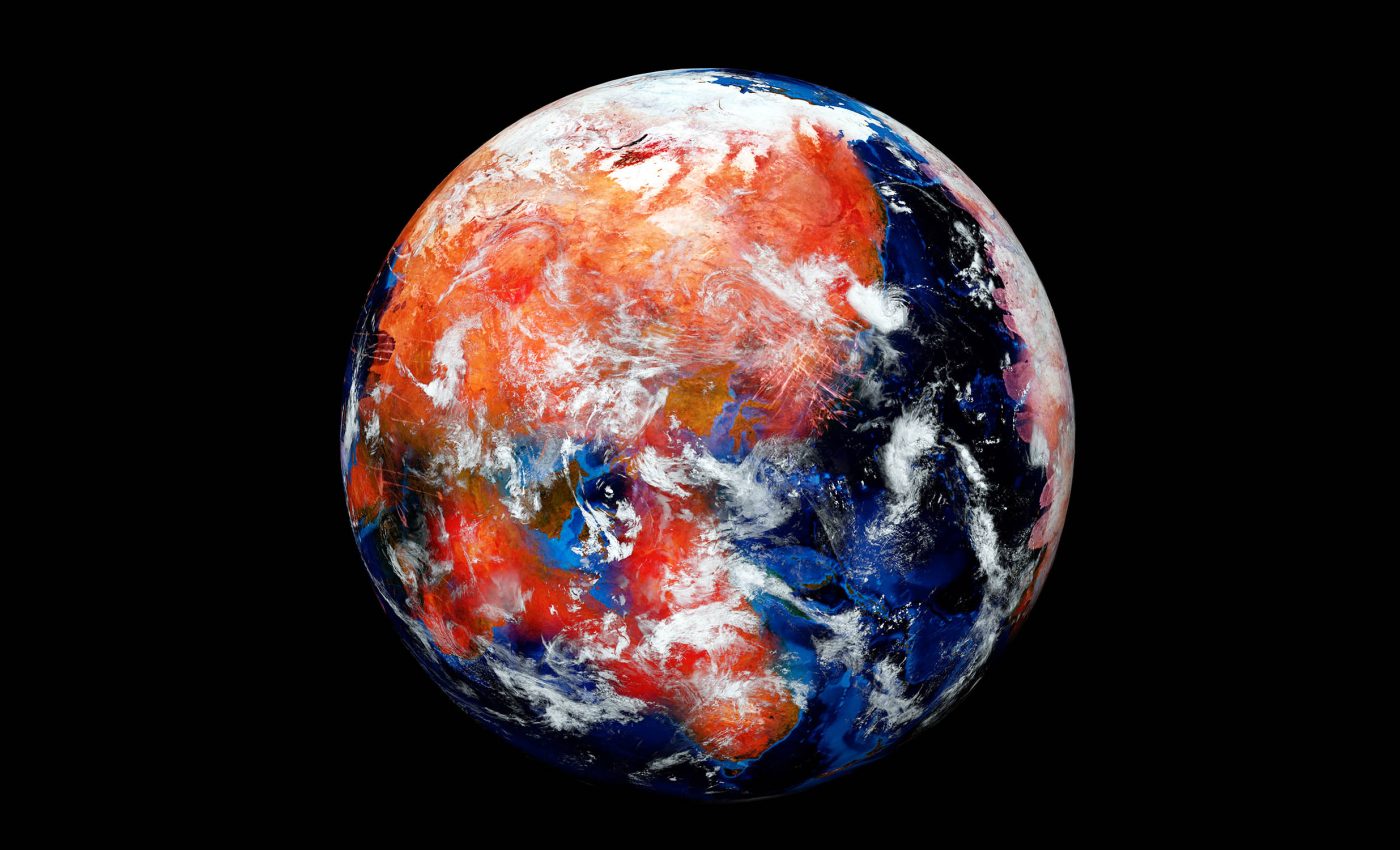

Ancient Egyptian astronomers would still recognize Mars today as the planet they called “Her Desher,” meaning “the red one.” Billions of years ago, however, liquid water on Mars’ surface and an atmosphere probably made it more like a blue world than a dry, Red Planet.

New measurements from NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft, now circling the planet, tie that watery past to a powerful escape process high above Mars.

They show that the atmosphere has been leaking away into space for billions of years, helping explain how a once blue world became a red desert.

From blue skies to red dust

The work was led by Shannon Curry, a planetary physicist at the University of Colorado Boulder and principal investigator for NASA’s MAVEN mission.

Her research focuses on how solar wind and radiation strip atmospheres from planets over time. Today Mars is about half Earth’s size, with a radius of 2,106 miles and a day that lasts 24.6 hours.

Its tilted spin axis gives it seasons that stretch out longer than ours, because the planet takes 687 Earth days to circle the Sun.

On average Mars orbits 1.5 astronomical unit, a standard Earth Sun distance used for measuring planets, away from the Sun. From that orbit it takes sunlight about 13 minutes to reach the planet’s upper atmosphere.

When Mars had an atmosphere

Orbital images reveal ancient river valleys, lake basins, and a canyon system more than 3,000 miles long etched into the crust.

Those landscapes are hard to explain without long lasting surface water flowing under a far denser sky.

Near the equator, NASA’s Curiosity rover drilled into fine grained mudstones at Yellowknife Bay inside Gale Crater.

Those rocks record a long lived lake with neutral pH, low salt content, and the basic chemical ingredients that simple microbes could have used.

Farther north, the Perseverance rover is now exploring an ancient delta, a fan of sediment left where a river once fed a crater lake in Jezero Crater.

Scientists chose that landing site because deltas tend to trap organic molecules and very fine grains that can preserve traces of past microbial life.

History of water on Mars

Taken together, the lake at Gale and the river system at Jezero build a picture in which sizable standing bodies of water once covered parts of Mars for long periods.

With thicker air and more water vapor overhead, those lakes and possible small seas would have made the planet look far more blue and Earthlike from space than it does now.

Conditions like neutral water, mild salinity, and available chemical energy are the basics for many microbes on Earth.

Finding that combination in Martian rocks, even from a single ancient lake, keeps astrobiologists focused on what other environmental clues might be preserved nearby.

Geologists interpret the layered sediments in Gale and Jezero as records of repeated wet and dry cycles.

Those stacked layers help them reconstruct when surface water was stable and when the climate began to dry out.

How Mars lost its atmosphere

Early in its history Mars probably had a global magnetosphere, a region of space shaped by a planet’s magnetic field that deflects charged particles from the Sun.

When that magnetic protection faded more than 4 billion years ago, the upper atmosphere became exposed to the full force of the solar wind.

One key escape process is atmospheric sputtering, in which energetic particles slam into atmospheric atoms and knock them into space.

On Mars those particles are mainly heavy ions from the solar wind that crash into the upper atmosphere along magnetic field lines.

At the same time, MAVEN observations show that water molecules carried high into the upper atmosphere break apart and release hydrogen that escapes into space, especially during dust storms and certain seasons.

A recent study found that these variations in hydrogen loss now dominate Mars’s ongoing water escape and strongly influence its climate evolution.

Sputtering seen in real time

In a recent analysis, Curry and colleagues used MAVEN’s argon measurements to map where sputtering is happening in the Martian atmosphere today.

They showed that heavy ions from the solar wind are actively blasting atoms away, directly confirming a process that had only been inferred from isotope ratios before.

“These results establish sputtering’s role in the loss of Mars’ atmosphere and in determining the history of water on Mars,” said Curry.

Her comment links a subtle process in the upper atmosphere to the dramatic climate changes recorded in dried up valleys and lakebeds far below.

By combining the present day sputtering rate with models of the younger Sun’s stronger solar wind, researchers conclude that sputtering likely removed a large share of Mars‘s original thick atmosphere.

That loss would have lowered surface pressure enough that liquid water could no longer remain stable for long on the ground.

From thick air to thin chill

Today the Martian atmosphere is extremely thin and made mostly of carbon dioxide, with only small amounts of nitrogen, argon, and oxygen.

With so little air overhead, the sky looks hazy and reddish from suspended dust, and harmful radiation from space reaches the surface far more easily than on Earth.

Surface temperatures now swing from highs near 70 degrees Fahrenheit on rare warm days to lows of about minus 225 degrees Fahrenheit at the poles.

Even near the equator at noon, a thermometer near your feet could read around 75 degrees while one held at head height barely reaches freezing.

Mars no longer has a global magnetic field threading through its core. Only patches of crust in the southern highlands remain strongly magnetized, relics of an earlier time when the planet’s interior was more active.

Lessons from Mars’ atmosphere

The emerging story is of a planet that began with blue lakes and perhaps small seas, then gradually lost the conditions that kept that water at the surface.

Habitability on Mars was probably limited to the time before most of the atmosphere escaped, when lakes such as the one in Gale Crater and the river system at Jezero were still active.

Curiosity, Perseverance, and MAVEN are now trying to pin down how long that window stayed open by reading chemistry locked into mudstones, salts, and the structure of the upper atmosphere.

If those samples eventually reveal convincing biosignatures, they will show not only that life once existed on Mars but also that it had enough time and stability to develop.

Understanding how Mars changed from a blue world to a red desert also helps researchers judge whether distant exoplanets can keep their own atmospheres and surface water.

It reminds us that even apparently stable planetary climates can be fragile when magnetic shielding, solar activity, and internal heat no longer stay in balance.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–