NASA satellite captures image of an enormous sewage spill in coastal waters

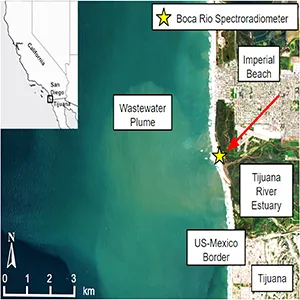

NASA’s imaging spectrometer riding on the International Space Station has spotted a wastewater plume pouring from the Tijuana River into the Pacific. The signal is strong enough that scientists can track the pollution from orbit with a single color feature.

The plume spreads along the South Bay shoreline where millions of gallons of wastewater move through the river each year. The team’s focus is a distinct dip in reflected light near 620 nanometers, a simple marker that stands out.

Wastewater plume seen from space

In a peer reviewed study, researchers matched what EMIT, a NASA imaging spectrometer that helps identify materials on Earth’s surface, saw from space with spectra measured in the lab and in the estuary.

The 620 nanometer feature increased as wastewater concentration rose, with several water quality measures showing very tight correlations, reaching R2 of at least 0.97.

The work was led by Eva Scrivner, University of Connecticut (UCONN). Her group traced the wastewater signal from the river mouth into coastal waters and showed how to map its shape without sampling every location.

How the instrument spots sewage

EMIT relies on imaging spectroscopy, a technique that captures hundreds of narrow colors at once. NASA’s instrument measures light across visible and infrared wavelengths to reveal the materials present.

The sensor records each scene at about 60 meter resolution, offering wide coverage and fine detail. That combination makes it possible to see the plume’s path in water where boats and waders cannot go safely.

One candidate behind the 620 nanometer dip is phycocyanin, a pigment in cyanobacteria that absorbs orange red light, which often rises in nutrient rich water. That possibility lines up with decades of remote sensing research.

The team has not pinned down the exact source yet. Another possibility is chromophoric dissolved organic matter, brown dissolved molecules that absorb blue light, which can co vary with sewage.

From lab bench to coastline

In the lab, the group mixed seawater with different amounts of untreated wastewater and measured reflectance from 350 to 2500 nanometers.

In the field, they compared those patterns to spectra from a shore based instrument and from EMIT scenes taken as the plume pushed south past the river mouth.

NASA highlighted the findings, noting that the satellite’s measurements closely matched field data and confirmed that EMIT can reliably detect coastal contamination from orbit.

Why this helps health agencies

Beach water safety warnings usually rely on grab samples and fixed sondes. Those tools are vital, but they leave gaps when contamination shifts quickly after storms or outfalls change.

Satellite maps can point samplers to the most affected zones on a given day. The 620 nanometer feature also tracks Enterococcus, a fecal bacteria used as a health indicator, which helps agencies decide where to test.

The method is not a replacement for lab tests. It is a fast screen that shows where conditions look worst, so teams can choose the most informative sampling sites and avoid risky areas.

As repairs advance under a binational agreement, including a plan to complete key projects by 2027, the agreement frames how satellite maps could guide day to day decisions. Seeing the plume’s reach helps test whether fixes are working.

Mapping wastewater plumes

EMIT’s spectra reveal a trough near 620 nanometers and a nearby shoulder near 650 nanometers. The team used fluorescence line height, an index measuring the red glow in spectra, to track how that shoulder weakens with distance from the river mouth.

Pixels closest to the mouth show the deepest feature. Farther out, the feature flattens as seawater dilutes the plume, offering a clean way to outline the contamination.

EMIT’s broader track record

EMIT was built for dust mapping, but the same precision has also revealed gas leaks, allowing scientists to trace methane and carbon dioxide plumes back to their individual sources.

That history matters here. If one instrument can verify both air and water signals with the same level of care, local agencies can compare hazards using a single data stream.

The 620 nanometer signal may be a regional tracer tied to wastewater and co-existing pigments. Calibrating it for other coasts will take more field data, careful atmosphere correction, and tests across seasons.

Still, the approach offers an immediate benefit. It shows where to sample today and how far the sewage spread yesterday, which is often the missing piece for beach safety and cleanup crews.

The study is published in Science of the Total Environment.

Image credits: NASA/NOAA/ScienceAdvances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–