New clue found in the mystery of what triggers intense auroral displays

In the polar regions, auroras can light up the night in sweeping waves of color. These shifting lights hint at powerful forces moving high above Earth. A recent study from the University of Southampton found signals that provide new insight into the moments before each auroral surge.

The study strengthens our understanding of substorm origins and also links auroral behavior to wider planetary systems.

Charged particles from the sun rush along magnetic routes and collide with atmospheric gas.

“The aurora borealis and aurora australis are caused by charged particles from space colliding with atoms and molecules in our atmosphere,” explained study co-author Dr. Daniel Whiter.

Those collisions generate color, yet deeper triggers lie in the magnetosphere. Rising magnetic energy builds tension until sudden release sparks a substorm.

Markers of plasma instability

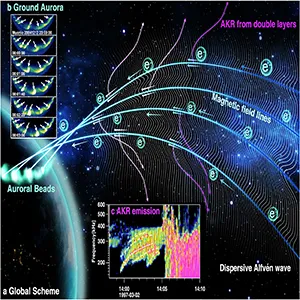

Small luminous points appear before each surge. Auroral beads form periodic chains with consistent spacing.

Ground cameras have recorded such chains for decades. Researchers now view each chain as a clear marker of plasma instability.

Azimuthal spacing, measured across many events, fits predictions for dispersive Alfvén waves interacting with magnetospheric plasma.

That pattern suggests wave activity already moves energy toward lower altitudes long before poleward brightening begins.

Periods often match values reported in earlier studies of wave power above the nightside auroral oval.

Radio signals and auroral displays

Auroral kilometric radiation (AKR) originates high above each glowing arc. Superposed epoch analyses from multiple missions show faint radio signals rising minutes before auroral motion begins. Observations reveal slowly drifting tones above 100 kilohertz.

Each tone shifts upward in frequency, marking source motion toward stronger magnetic fields. The research identifies ion acoustic speeds as the most likely driver of that motion.

Double layers, formed when Alfvén waves disturb plasma regions, move along field lines and generate those shifting tones.

Mapping of observed frequencies to electron cyclotron frequencies places source regions between 2,000 and 8,000 kilometers. That altitude range aligns with expected sites of auroral acceleration.

A careful survey of archival spacecraft data shows hundreds of such precursor events. Many contain repetitive drifting tones with stable periods. Those periods match auroral bead spacing found in long-term ground records.

Waves drive energetic changes

Wave-like arcs evolve in tandem with radio tones. Cameras often reveal two phases. A first local brightening lasts several minutes and fades.

A second structured arc appears shortly before a substorm and expands poleward. Radio tones echo that sequence.

Faint drifting features form during early brightening, fade, then return in stronger form during the build-up to expansion.

Alfvén waves appear central to each link. Dispersive forms of those waves carry energy earthward from the magnetotail.

Once reaching lower altitudes, wave fronts disturb plasma and energize electrons. That process activates double layers, which then slide along magnetic field lines.

Consistent pattern of aurora signals

Each sliding layer produces a drifting tone. Electron acceleration near each layer contributes to auroral brightening along connected field lines.

Research teams report remarkable consistency between wave periods, drift speeds, and auroral bead behavior.

Auroral beads show clear azimuthal motion. That motion creates periodic brightening for any camera fixed on a single region. When mapped along field lines, the same periodicity appears as a rhythm in radio tones.

Multiple waves moving

Repetition periods often fall between 30 and 90 seconds. Those periods match values seen in ultra-low-frequency wave studies linked to substorm growth.

Each value points toward a unified process shaped by Alfvén wave coupling.

Ion acoustic speeds match observed drift velocities far better than Alfvén speeds. That finding rules out free electron motion and implies a structured electric environment. Double layers satisfy many requirements.

Each layer forms when wave fronts interact with inhomogeneous plasma. The layer then moves along a field line and leaves a radio signature.

Multiple layers moving in sequence generate multiple drifting tones and create a coherent frequency pattern.

Signals before auroral displays

Similar drifting radio signatures appear near Saturn and Jupiter. Observations from previous missions show frequency-drifting emissions at rates far higher than Earth examples.

Plasma conditions around giant planets enable rapid motion of electric structures. Alfvén waves also guide energy flows there.

Studies of Jupiter even reveal radio bursts tied to interactions with moons, again dominated by Alfvénic activity.

Such parallels support a broader idea. A shared mechanism may operate across magnetized worlds.

Double layers, shaped by Alfvén waves, shift along magnetic lines and generate drifting radio signals. Auroral features glow where field lines intersect planetary atmospheres.

Each world expresses the same physics under unique plasma conditions, yet key patterns remain recognizable across multiple systems.

Future research directions

Research from Southampton strengthens a rising view of substorm origins. Auroral beads mark early plasma structure. Drifting radio tones mark moving double layers.

Alfvén waves supply energy to both. Each link offers clues about magnetospheric timing and energy flow. Substorm expansion begins only when energy motions converge and produce rapid brightening across wide arcs.

Future research will refine altitude estimates, timing windows, and electron dynamics. Yet current results already connect optical features and radio emissions in new ways.

Each combined dataset draws auroral science closer to a unified understanding of sudden bright nights in polar skies.

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–