New early Homo species discovered that challenges "ape-to-human" evolution theory

The story of human evolution is not a simple ladder from early forms to more advanced ones. For decades, fossils shaped a picture of steady, linear progress – one form giving rise to another in a neat sequence.

But science often rewrites its narratives when new evidence appears. Now, remarkable finds in Ethiopia are challenging long-held assumptions and painting a richer, more intricate picture of our origins.

Recent fossil discoveries in Ethiopia suggest that our evolutionary past was far more complex than a simple linear progression.

Research led by UNLV anthropologist Brian Villmoare, in collaboration with the Ledi-Geraru Research Project, has revealed that Australopithecus and early and unidentified Homo species coexisted between 2.6 and 2.8 million years ago in the same part of Africa.

These findings challenge the traditional “march from ape to human” model and instead support the idea of a branching tree with multiple lineages.

Understanding Australopithecus – the basics

Australopithecus walked the African landscape around 3 million years ago, bridging the gap between our ape-like ancestors and modern humans.

They stood upright, though shorter and smaller-brained than us, and their mix of traits – long arms for climbing, but pelvis and legs built for walking – shows how they lived in both trees and open grasslands.

Fossils of species like Australopithecus afarensis, best known from the famous skeleton “Lucy,” reveal that these early hominins were already experimenting with bipedalism while still relying on arboreal agility.

What makes Australopithecus so fascinating is the story their bones tell about adaptation. They didn’t use tools the way later hominins did, but they set the stage for it by freeing their hands once walking became the norm.

Their teeth and jaws suggest a varied diet, probably fruits, roots, and tougher plants, helping them survive in shifting environments.

Australopithecus lived with others

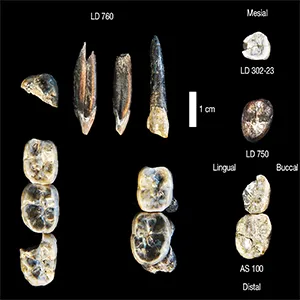

At the Ledi-Geraru site, scientists found 13 teeth. Some belonged to early Homo, while others came from a previously unknown Australopithecus species.

The latter is different from the famous Australopithecus afarensis skeleton, known as “Lucy,” that disappeared from the fossil record around 2.95 million years ago.

The research showed no evidence of Lucy’s kind aged any younger than 2.95 million years.

“This new research shows that the image many of us have in our minds of an ape to a Neanderthal to a modern human is not correct – evolution doesn’t work like that,” said ASU paleoecologist Kaye Reed.

“Here we have two hominin species that are together. Human evolution is not linear – it’s a bushy tree, there are life forms that go extinct.”

Site shows oldest Homo and tools

Ledi-Geraru is already well known in paleoanthropology. It has produced the oldest known Homo jaw fossil, dated to 2.8 million years ago, and the earliest Oldowan stone tools.

The site’s sediments, which are rich in volcanic ash, allow precise dating.

Crystals in the ash, called feldspars, are key for determining the ages of fossils, as they can be dated from volcanic eruptions above and below the fossil layers.

This geological context also provides clues about the environment in which these species lived.

Australopithecus territory had rivers

Two to three million years ago, the Ledi-Geraru area was a dynamic landscape of rivers, vegetation, and shallow lakes that expanded and shrank over time.

This is a stark contrast to today’s faulted badlands.

Geological evidence indicates that the region preserved an interpretable record for the period from 2.3 to 2.95 million years ago – a crucial time in terms of human evolution.

Multiple lineages, multiple niches

The study concluded that before 2.5 million years ago, eastern Africa may have had as many as four hominin lineages: early Homo, Australopithecus garhi, the newly discovered Ledi-Geraru Australopithecus, and potentially others in nearby regions.

“We used to think of human evolution as fairly linear, with a steady march from an ape-like ancestor to modern Homo sapiens,” Villmoare said.

Instead, humans branched out multiple times into different niches.

“Our pattern of evolution is not particularly unusual, and what has happened to humans has happened to every other tree of life.”

Tooth enamel holds hidden answers

Detailed analysis of the teeth showed differences from known Australopithecus and Homo specimens.

These distinctions suggest the Ledi-Geraru Australopithecus was neither a late-surviving A. afarensis nor A. garhi, but rather a previously unknown species.

However, the team has not yet named it, as more fossils are needed for a full classification.

Researchers are now studying the tooth enamel to understand diet and possible interactions between early Homo and this Australopithecus species.

More study is needed

Key questions remain: Did they compete for food or share resources? How often did they encounter each other? Who were their ancestors?

“Whenever you have an exciting discovery, if you’re a paleontologist, you always know that you need more information,” Reed explained. “You need more fossils.”

“That’s why it’s an important field to train people in – and for people to go out and find their own sites and explore places where we haven’t yet found fossils.”

More finds could reveal not just how these species lived but also why some survived while others vanished.

The study is published in the journal Nature.

Image Credit: Kaye Reed, Arizona State University.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–