New species of mollusk discovered at the bottom of the ocean

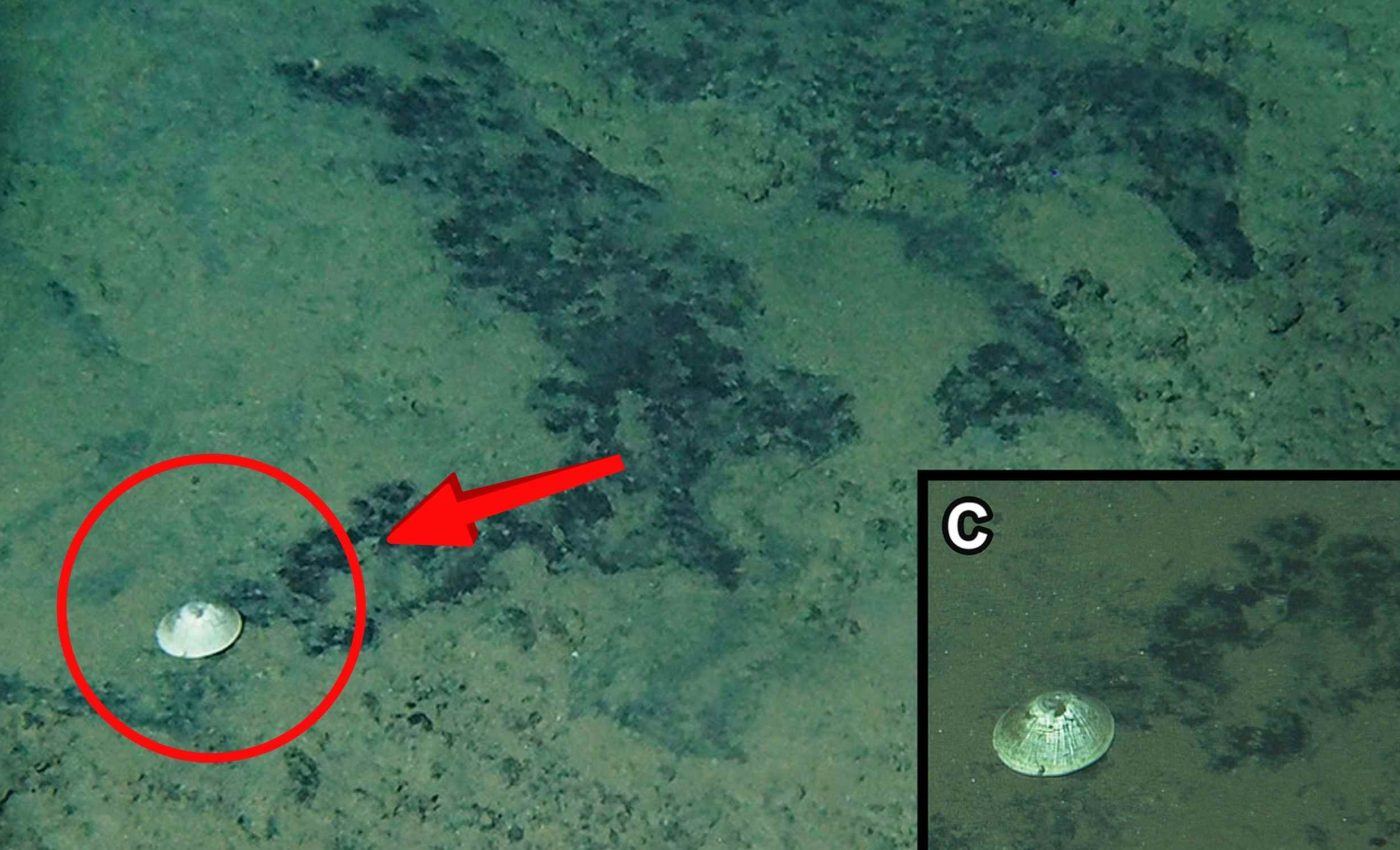

About 300 miles (480 kilometers) southeast of Tokyo, a crewed submersible peered at a ledge of volcanic rock and spotted something unusual. A limpet with a thin, bluish shell sat on the rock at a depth of about 19,430 feet (6 kilometers).

The single encounter with this mollusk has now expanded a whole branch of the tree of life, adding a new name and a new record.

The limpet species is Bathylepeta wadatsumi, and it belongs to a group of true limpets that usually live in shallow tide pools. This one was living far below that zone, on the normal deep seafloor where light never reaches.

Bathylepeta wadatsumi

The shell reaches 1.6 inches (40.5 millimeters) long, which is large for a limpet living so deep.

The shell is “thin, translucent, bluish grey, slightly elastic, possibly reflecting high organic content,” wrote Chong Chen, lead author and senior scientist at the Japan Agency for Marine Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC).

The mollusk under the shell is reddish brown, with an oval, muscular foot that helps it move.

The shell carries clear white streaks that radiate from the top toward the edge, and those lines are part of how scientists tell species apart.

The limpet was sitting on a rocky escarpment, dusted with a thin layer of sediment. A curving trail behind it showed that it had grazed over that sediment for food.

“Several individuals were sighted from the viewport of the submersible, but only one individual, the holotype, was successfully collected,” wrote Chen.

The collected specimen anchors the new name to a real animal that any researcher can check in a museum.

Why Bathylepeta wadatsumi matters

For a long time, many people pictured the abyss as a flat, muddy plain. Recent research shows that rocky patches are more common than expected, and those hard surfaces host distinct communities.

Finding Bathylepeta wadatsumi on bare rock this deep adds weight to that update. It hints that more species likely live on scattered rock outcrops, and that our nets and sleds often miss them.

Taxonomy does not end at a pretty shell. The team combined standard anatomy with DNA from the COI gene to place the species within its family, then tested relationships against other limpets using a tree building approach.

That broader context lines up with recent phylogenomic analysis suggesting a single event when true limpets moved into deep water.

They later branched into several different families. This new species fits that big picture while extending the known depth limit for its entire group.

Comparing to other limpets

Two relatives of Bathylepeta wadatsumi were known before this one, one from Antarctica and one from off Chile.

The Antarctic species, Bathylepeta linseae, was first described in 2006 and differs in shell shape and the details of its scraping mouthparts.

The new limpet is larger and shows stronger development in certain teeth on the radula, the ribbon-like band of teeth that limpets use to scrape food from surfaces.

These differences, along with genetic distance, clinch its status as a separate species.

Depth matters in biology because pressure, temperature, and food supply change with distance under the sea. Living at about 19,430 feet (6 kilometers) underwater sets a new deepest record for any patellogastropod, the clade that includes true limpets.

A record like this also flags a habitat type that needs more attention. Rocky ledges in the abyssal plain are patchy and hard to sample, so the species that cling to them often go unseen.

What this says about exploration

“The use of submersibles has been instrumental in accessing these habitats, allowing for direct observation and collection of organisms like Bathylepeta that were previously overlooked,” wrote Chen. Crewed dives let researchers follow a feeding trail, inspect a surface, and make a quick decision to sample.

That is how one limpet on a ledge became a holotype with a name, a museum record, and a place on the family tree. Tools open doors, but attentive eyes make the calls that change our species lists and maps.

Learning from Bathylepeta wadatsumi

The limpet’s trail shows it grazes on the dusting of fine material that settles on the rock. That makes sense for a large true limpet that lives where food falls from above in tiny flakes.

A strong jaw, a reinforced scraping edge, and large, curved, marginal teeth match that feeding style. Those traits let this mollusk sweep and scrape soft films from hard stone surfaces without any drifting away.

The observation of this mollusk off Japan suggests the genus may span wide stretches of deep ocean, from the South Pacific to the northwest Pacific, with gaps caused by how rarely we visit these cliffs and fault lines. Each new dive along similar rocky features could turn up more individuals, or even more species.

If that happens, museum collections, DNA data, and careful images will help sort out how these animals spread, adapt, and persist in the pitch dark. That is how a single find can sharpen both a species description and a map of deep-sea life.

The study is published in Zoosystematics and Evolution.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–