New trail cams reveal that an old human bridge became a safe trail for Amazon animals

Camera traps have revealed a hidden rush hour in the Amazon canopy. Over three weeks, researchers documented mammals quietly moving along a tourist walkway at the Amazon Conservatory for Tropical Studies (ACTS) near Iquitos, Peru. They were using human-built bridges as nighttime highways.

The elevated platforms, stretching 20 to 118 feet (6 to 36 meters) above the ground, weren’t designed for wildlife.

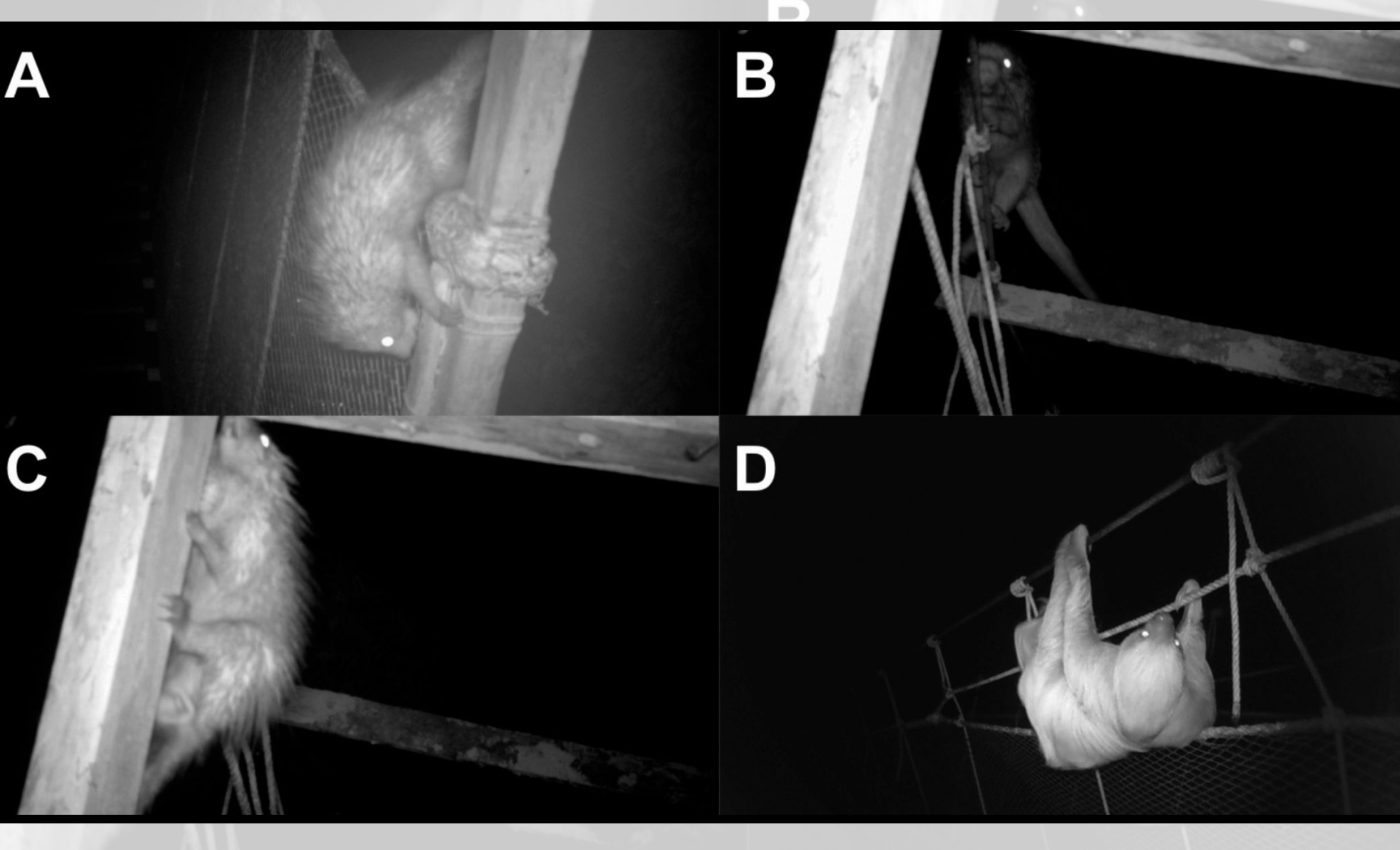

But the footage shows seven mammal species treating them as safe, suspended routes through the forest, offering a rare look at how arboreal animals navigate an increasingly fragmented Amazon.

Animals that used the Amazon walkway

The work was led by Lindsey Swierk, an assistant professor of biological sciences at Binghamton University. Her research centers on animal behavior and conservation, and she helps guide field programs at the ACTS site.

The ACTS canopy walkway is made up of elevated bridges and platforms that connect treetops for people.

These structures can also serve animals that avoid the ground. In fragmented forests, such structures may link food, shelter, and mates separated by gaps.

Animals recorded included two-toed sloths, several porcupines, a woolly opossum, a saki monkey, and a spiny rat. Sloths and long-tailed porcupines were the most frequent users during the survey window.

The Amazon holds extraordinary animal diversity that can benefit from overhead crossing points. According to WWF counts, the region is home to 427 mammal species – many of which spend long hours in the trees.

Animal traffic jam at night

The team found most animal movements between about 7:00 p.m. and 9:00 p.m., a narrow window at the start of the night.

Mid-canopy levels around 70 to 90 feet (21 to 27 meters) drew the most crossings, with fewer visits higher and lower.

Night activity on the walkway stood out in the recordings, with researchers noting that arboreal mammals tend to be shy and well camouflaged during the day but become more active and mobile after dark.

These patterns track a daily rhythm called the diel cycle, the 24-hour day and night activity cycle. It often concentrates feeding and travel into a few hours after dusk for species that avoid daytime disturbance.

Conditions likely played a role as well. The team measured warmer, slightly windier air higher up and higher humidity nearer the ground.

This microclimate – local temperature and moisture patterns that shift with height – can shape when and where animals move.

Design lessons for wildlife bridges

As roads and clearings slice through forests, habitat fragmentation – the breaking of continuous habitat into isolated patches – can turn a short gap into a deadly barrier for tree-dependent mammals. Overhead structures offer an alternative path that keeps animals off the road.

Previous research that monitored natural canopy bridges over a pipeline in Peru found crossing rates more than 100-times higher above ground compared with the ground below.

Those results point to simple design features, like multiple connections and good foliage cover, that boost use.

The new findings add a practical detail for engineers and park managers. Most traffic occurred in the mid-canopy, so bridges at that level may see more use than very high spans.

The researchers noted that as forests become increasingly fragmented, artificial canopy structures can offer safer routes for tree-dwelling animals. These crossings help them avoid dangerous ground routes where road deaths are more likely.

A bigger Amazon picture

The Amazon’s wildlife is both abundant and hidden. Many species are arboreal, animals that spend most of their lives in trees, which makes them easy to miss from the ground.

Walkways allow researchers to place cameras where animals actually travel in the Amazon. They also let managers test whether a crossing is at the right height or needs better links to nearby branches.

Because the forest supports so many species, the payoffs can be broad. A well-placed bridge helps porcupines one night and an opossum the next while leaving the ground safer for both wildlife and people.

The team’s records suggest canopy corridors are most useful right after sunset. That simple timing note can guide when to limit human traffic on tourist walkways to reduce disturbance during peak movement.

Insights from walkway footage

Four camera trap stations ran continuously for 21 days at about 40, 68, 87, and 110 feet (12, 21, 27, and 34 meters) above ground.

The setup captured movement along rope rails and beams, and it showed that the walkway floor itself drew little use from wildlife.

During the formal survey window, all documented crossings occurred at night. Outside that window, observers saw a sloth and a saki monkey on the walkway during daytime when visitor traffic had eased.

The mid-canopy preference emerged clearly in the logs. That detail is actionable, because it points to the level where a bridge is most likely to work as a connector between trees.

Together, these records supply a rare overhead view of everyday behavior. They also provide baseline numbers that future projects can use to test seasonal differences or redesign spans in fragmented areas.

The study is published in Neotropical Biology and Conservation.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–