Ocean temperatures are rising faster than expected, and likely to accelerate

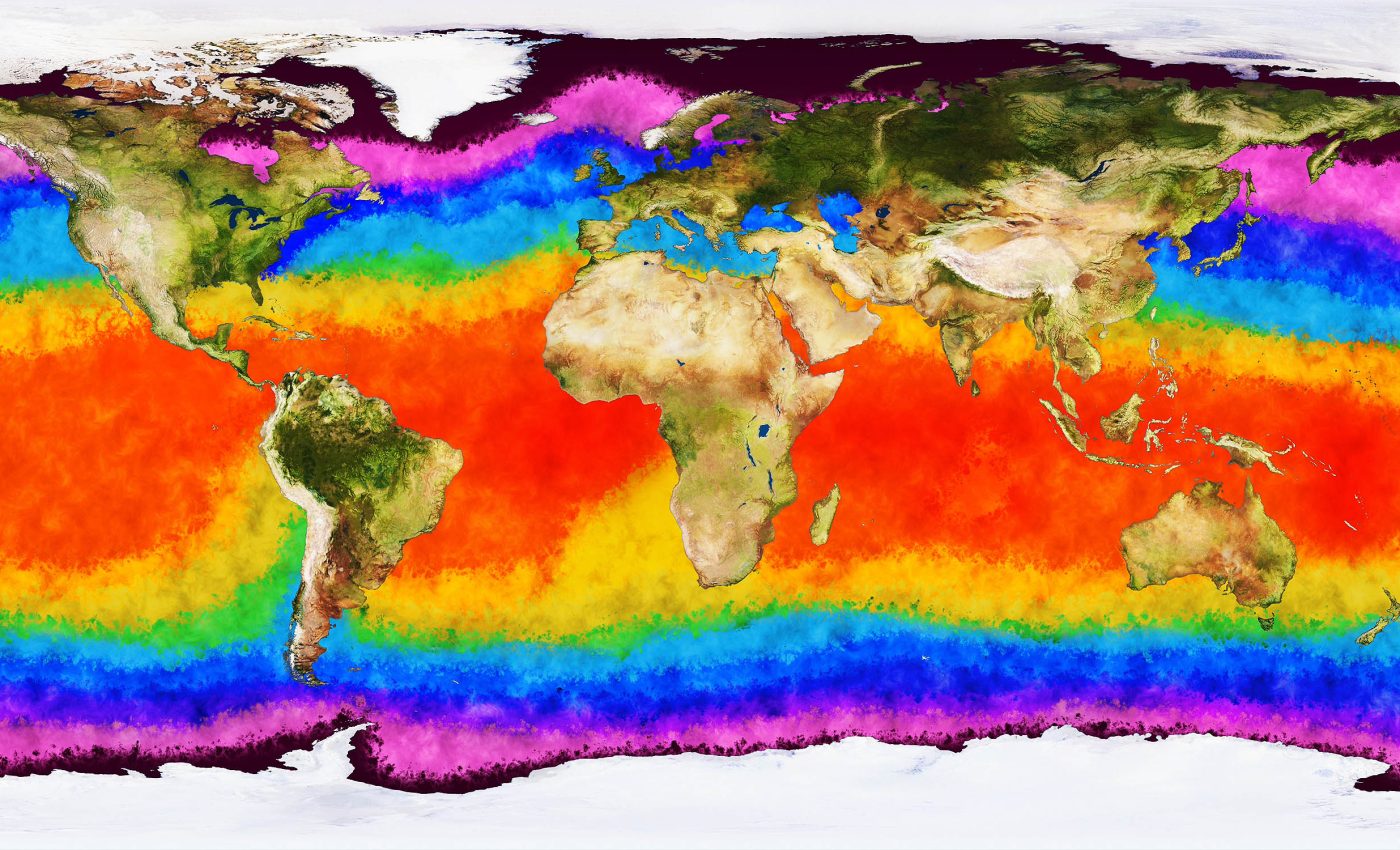

Satellite instruments that have been circling Earth since the early 1980s now paint a stark picture of our warm ocean temperatures: not only are they rising, they are doing so more quickly with each passing decade.

According to a new study, between 1985 and 1989, global averages increased by about 0.06 °C every ten years.

In the most recent five‑year collection of data from 2019 to 2023, that figure leapt to roughly 0.27 °C per decade. In practical terms, the thin skin of water covering our planet is heating more than four times faster today than it was a generation ago.

Long-term record of ocean temperatures

The researchers analyzed sea‑surface temperature (SST) fields created through the European Space Agency’s Climate Change Initiative (ESA-CCI SST). They stitched together a single, carefully calibrated record extending from 1980 right up to 2023.

The experts took measurements from 20 satellite‑borne infrared radiometers, including sensors on missions such as ERS‑1, ERS‑2, Envisat and Copernicus Sentinel‑3, together with two microwave instruments that penetrate cloud cover at high latitudes.

Each satellite required meticulous cross‑calibration; otherwise, subtle drifts in sensor performance or orbital changes might be misread as genuine changes in ocean heat.

By comparing satellite values with data from ships and drifting buoys, the team produced what is currently one of the world’s most reliable long‑term SST series.

Trapped heat and energy imbalance

With data in hand, investigators set out to identify the forces responsible for the accelerating climb. They examined volcanic eruptions, which sometimes cool the Earth’s surface for a year or two by shading incoming sunlight.

The team also mapped out the impacts of recurring El Niño and La Niña events that alternately cool and warm oceans. Solar cycles, which raise or lower the Sun’s energy output on an eleven‑year rhythm, were also weighed.

Although each of these natural processes leaves a recognizable fingerprint, none could explain the long‑running upward trend, much less the recent acceleration. The prime driver, the authors conclude, is the long‑term energy imbalance caused by the build‑up of greenhouse gases.

Greenhouse gases trapping heat in the atmosphere result in an imbalance in the energy received by our planet from the Sun, while the energy radiates back out to space, resulting in an excess energy imbalance, according to lead author Chris Merchant from the University of Reading.

To keep pace with the changing climate, he added, “we need ongoing monitoring and data improvements to ensure our climate models can accurately reflect future temperature increases.”

Dominant driver of ocean warming

Owen Embury, scientific lead for the ESA‑CCI SST project, elaborated on the balance between short‑term fluctuations and the persistent warming signal.

“Our study clearly identifies the increasing accumulation of planetary energy as the dominant driver of long‑term sea surface warming, while short‑term variations from El Niño, volcanic activity and solar changes add variability but do not alter the overall accelerating trend,” he explained.

The research therefore disentangles the temporary bumps and dips from the steadily ticking metronome of human‑driven change. Mounting heat in the oceans does more than shift a thermometer reading.

Warmer surface water supplies extra fuel for tropical cyclones, allowing storms to intensify faster and reach higher peak winds. As temperature thresholds are crossed, coral reefs bleach, fisheries relocate, and weather patterns on land alter in response to changed heat exchange between sea and atmosphere.

Warmer water also expands, pushing sea level upward alongside meltwater from ice sheets and glaciers. These knock‑on effects affect everything from coastal infrastructure to global food security.

Forecasting future ocean temperatures

Because consequences of accelerating ocean warming reach into many corners of society and the biosphere, the findings have already been integrated into ESA’s MOTECUSOMA project, which examines Earth’s energy imbalance and its downstream effects.

The same SST data set will also serve as a touchstone for refining climate models, which must reproduce the observed rate of heat uptake if they are to forecast future conditions credibly.

“Addressing these challenges requires accurate climate projections – increasing ocean heat uptake intensifies extreme weather events, disrupts ecosystems, and accelerates sea level rise, making continued observation and model refinement essential,” Embury said.

A call for vigilance

Looking ahead, several forthcoming satellite missions promise to sharpen the picture further. Additional Copernicus Sentinel‑3 satellites will lengthen the infrared record, while ESA’s proposed TRUTHS mission plans to carry an ultra‑stable reference spectrometer.

The spectrometer will improve calibration across the entire suite of Earth‑observing instruments. Such advances are vital, because even small errors in measuring the ocean’s surface can accumulate into large uncertainties about total planetary heat.

Although the new study focuses on sea‑surface temperature, the implications extend well beyond. Surface warming is often just the tip of the iceberg.

Heat propagates downward on timescales of decades to centuries, altering currents, destabilizing ice shelves from below and setting the stage for further climate shifts long after atmospheric greenhouse‑gas levels are stabilized.

By tracking the surface layer with high precision, scientists gain clues about how much thermal energy is entering the deeper ocean and how quickly.

Human influence on ocean temperatures

The quadrupling of the warming rate since the late 1980s serves as a sobering marker of humanity’s influence on the climate system. It illustrates not only that the oceans are acting as a buffer, absorbing enormous amounts of excess heat, but also that this buffer is filling up faster than before.

Continued satellite surveillance of warm oceans, combined with in‑situ measurements and refined climate models, provides the clearest picture yet of how and why the ocean is changing – and helps societies plan responses.

Whether the next forty years see another acceleration or a slowdown will depend largely on how soon and how vigorously global greenhouse‑gas emissions are curbed.

The study is published in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–