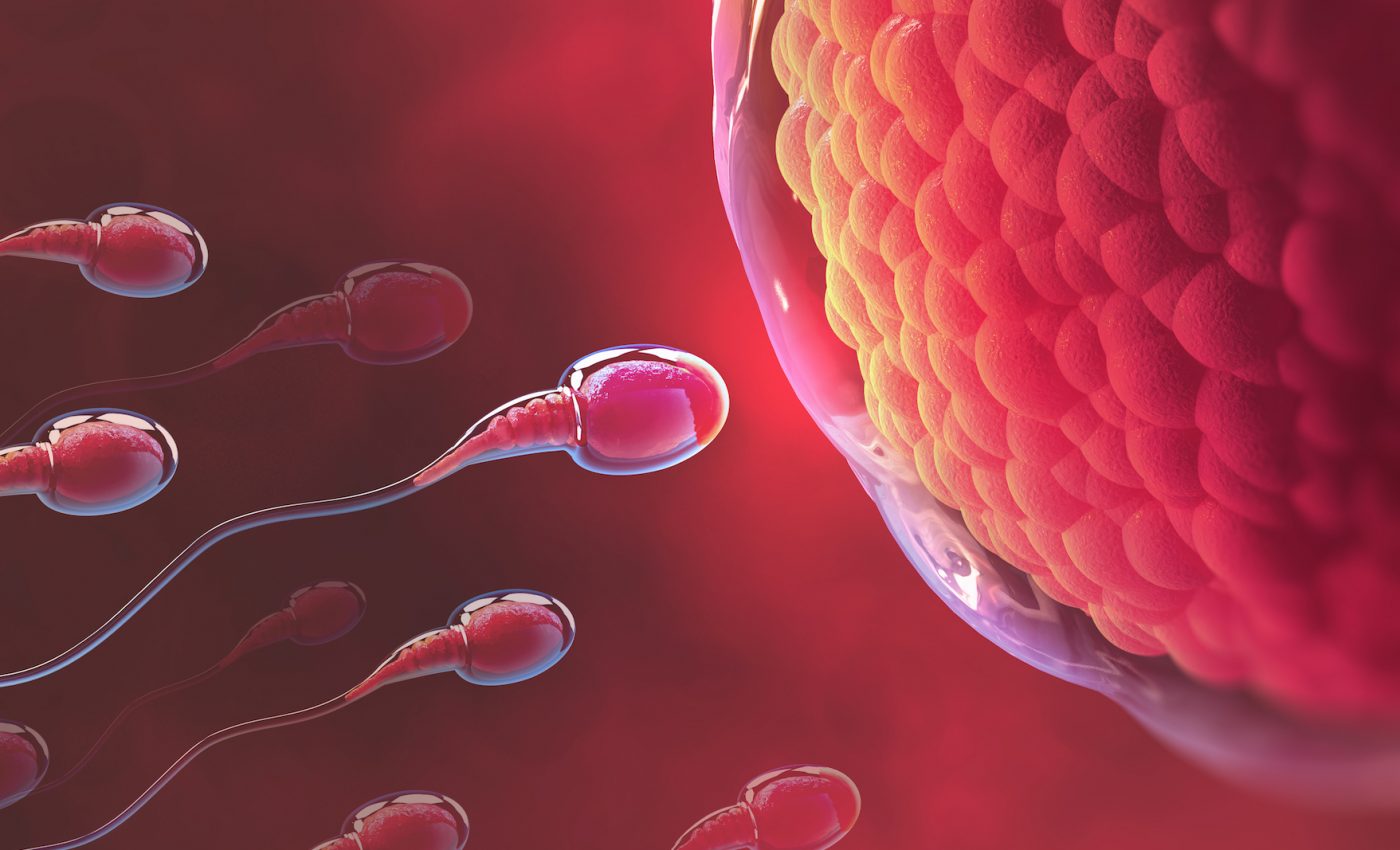

New research shows that older sperm created healthier offspring

A study led by the University of East Anglia has revealed that “older” sperm produce healthier offspring. According to the researchers, sperm that have lived longer before fertilizing an egg not only have a positive impact on the health and lifespan of their own offspring, but also on the generation that follows.

The analysis, which also involved experts from Uppsala University, was focused on the shorter- and longer-lived sperm in the same ejaculate of a male zebrafish. The findings may have important implications for human reproduction and fertility, particularly for informing assisted fertilization techniques.

“One male produces thousands to millions of sperm in a single ejaculate but only very few end up fertilizing an egg,” said lead author Dr. Simone Immler. “The sperm within an ejaculate vary not only in their shape and performance, but also in the genetic material that each of them carries.”

“Until now, there was a general assumption that it doesn’t really matter which sperm fertilises an egg as long as it can fertilize it. But we have shown that there are massive differences between sperm and how they affect the offspring.”

The research team collected both male and female gametes, and then split the ejaculate of a male into two halves. In one half, they selected for shorter-lived sperm and in the other for longer-lived sperm. The sperm were then added to two half clutches from a female to fertilize the eggs. The resulting offspring were reared into adulthood and monitored throughout their lifespans.

“We found that when we select for the longer-lived sperm within the ejaculate of male zebrafish, the resulting offspring is much fitter than their full siblings sired by the shorter-lived sperm of the same male,” said Dr. Immler.

“More specifically, offspring sired by longer-lived sperm produce more and healthier offspring throughout their life that age at a slower rate. This is a surprising result, which suggests that it is important to understand how sperm selection may contribute to the fitness of the next generations.”

The study is published in the journal Evolution Letters.

—

By Chrissy Sexton, Earth.com Staff Writer