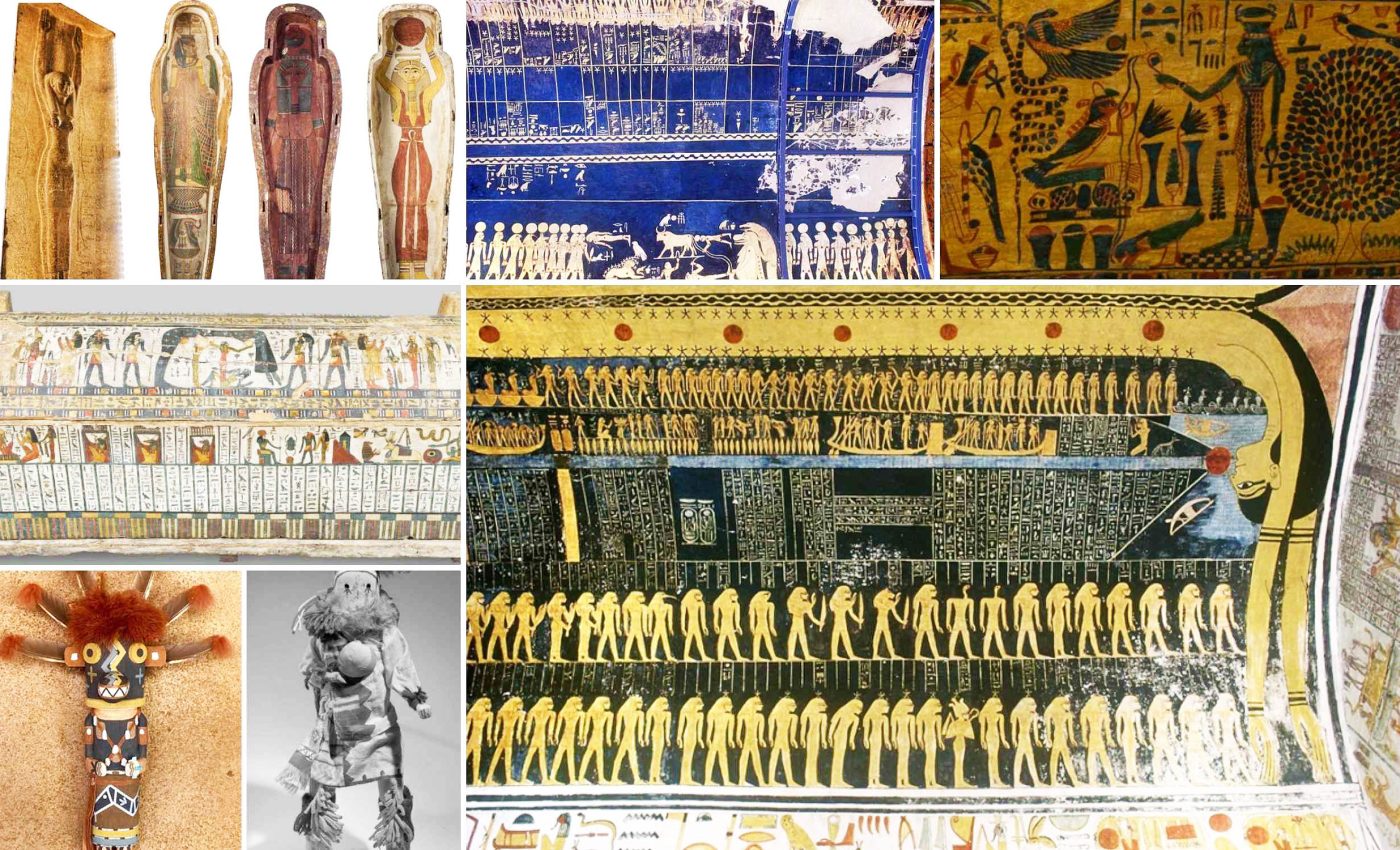

Oldest depiction of the Milky Way galaxy discovered in an Egyptian sarcophagus

The oldest known depiction of our galaxy may come from a coffin that once held an ancient Egyptian priestess. Thousands of years ago, early observers around the Nile watched the night sky and recorded what they saw in ways that still surprise people today.

Their cosmic understanding went beyond casual observation, given the care they took in mapping stars and planetary positions.

These efforts shaped myths and religious beliefs that included powerful deities who represented the sky itself.

The presence of such a depiction was proposed by Or Grauer from the University of Portsmouth.

He explored museum collections for images of Nut, the Egyptian goddess of the sky, and found an unexpected detail on a coffin belonging to Nesitaudjatakhet.

Egyptians and the night sky

Ancient Egyptian society thrived along the banks of the Nile, where seasonal floods influenced farming and daily life.

The night sky became a reference point for these rhythms, prompting the Egyptians to begin making detailed observations of celestial patterns.

Priests tracked the rising and setting of stars to guide religious events, marking out constellations with local symbolism.

Astrophysicists and historians now suggest these same patterns shaped how the Egyptians understood their gods and the wider firmament.

In one striking coffin scene, Nut’s figure arches over the earth, with an undulating curve traced from her fingertips to her toes. This dark curve cuts through the stars on her body, leaving some above and others below.

“A comparison with a photograph of the Milky Way shows the striking similarity between the wavy curve that runs through Nut’s body and the wavy curve created by the dark nebulae that make up the Great Rift,” said Dr. Grauer.

It appears to match the Great Rift, which is the band of interstellar dust that seems to bisect the Milky Way.

Deepening our view of nut

While Nut was often pictured as the entire Egyptian night sky, she did not always show a visible reference to the Milky Way. Many coffin artworks depict her naked or clothed but typically avoid that wavy band.

The feature in Nesitaudjatakhet’s coffin stands out because the curve is thick, dark, and divides her starry form. This is why some experts now consider it the earliest known artistic sign of the Milky Way in Egyptian funeral iconography.

Much of Nut’s representation involved the path of the Sun and stars as she swallowed them at dusk and birthed them at dawn.

Egyptians also described the sky in texts that link it to a “Winding Waterway,” which some believe could be a name for our galaxy.

The faint dust clouds that form the Great Rift are easy to notice under dark skies, so it is possible that ancient astronomers saw this feature splitting the glow of the Milky Way.

Whether they specifically labeled it as a cosmic river or associated it with Nut’s form remains a point of discussion.

Connecting religion and astronomy

The knowledge carved and painted into these burial items reflects a society that saw religion and astronomy as one connected system.

Egyptian night sky lore spanned the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars, with deities representing cosmic forces.

Nut’s cosmic curve is just another reminder of how carefully people watched the heavens in earlier times. Today, it serves as both a historical clue and a symbol of human curiosity.

rows of yellow half-circles that border the two halves of the ceiling. Click image to enlarge. Credit: Theban Mapping Project, Photographer, Francis Dzikowski

Elsewhere, other civilizations also likened the Milky Way’s cloudy band to rivers and pathways. In classical Greece, it was called the “Galaxy,” rooted in legends of milk sprayed across the sky.

The Egyptian approach put the galaxy within a goddess’s silhouette, linking cosmic wonder to stories of birth and rebirth. This bond between visual art and faith explains why coffins became a central place for these images.

Why does any of this matter?

Experts point to the 21st and 22nd Dynasties as times of vibrant coffin designs, combining older funerary customs with new artistic ideas.

Burial sets often had layers, each with religious scenes that showed various deities and protective formulas.

A person like Nesitaudjatakhet, who served as a musician and chantress, held a high rank in temple society. The images around her final resting place likely merged theology with cosmic symbolism.

Egypt and the ancient night sky

Those who research early astronomy continue to wonder if Egyptian priests fully understood the galaxy’s shape or only noticed its brighter patches.

The presence of the Great Rift suggests they recognized distinct zones in the band of light crossing the night sky.

This raises the question of whether the “Winding Waterway” refers to that dark split within the glowing path. Though we may never know their exact thoughts, the coffin detail hints that they observed far more than modern assumptions might suggest.

Even without telescopes, ancient stargazers formed complex ideas about planetary alignments and seasonal changes. They excelled at linking natural cycles to myths, weaving them into every aspect of life and the afterlife.

Nut’s starry figure and that striking curve demonstrate how ancient theology and observation blended into a single story. It is an unusual view of the sky that still holds our attention today.

The study is published in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–