Perfectly preserved ichthyosaur skeleton is identified as a new species

Fossils tell stories of life that vanished millions of years ago. Some discoveries confirm what scientists already expected, while others challenge the record and force new questions.

In southern Germany, one discovery has done exactly that. An international team described a new ichthyosaur species, and its story begins in a quiet Bavarian clay pit.

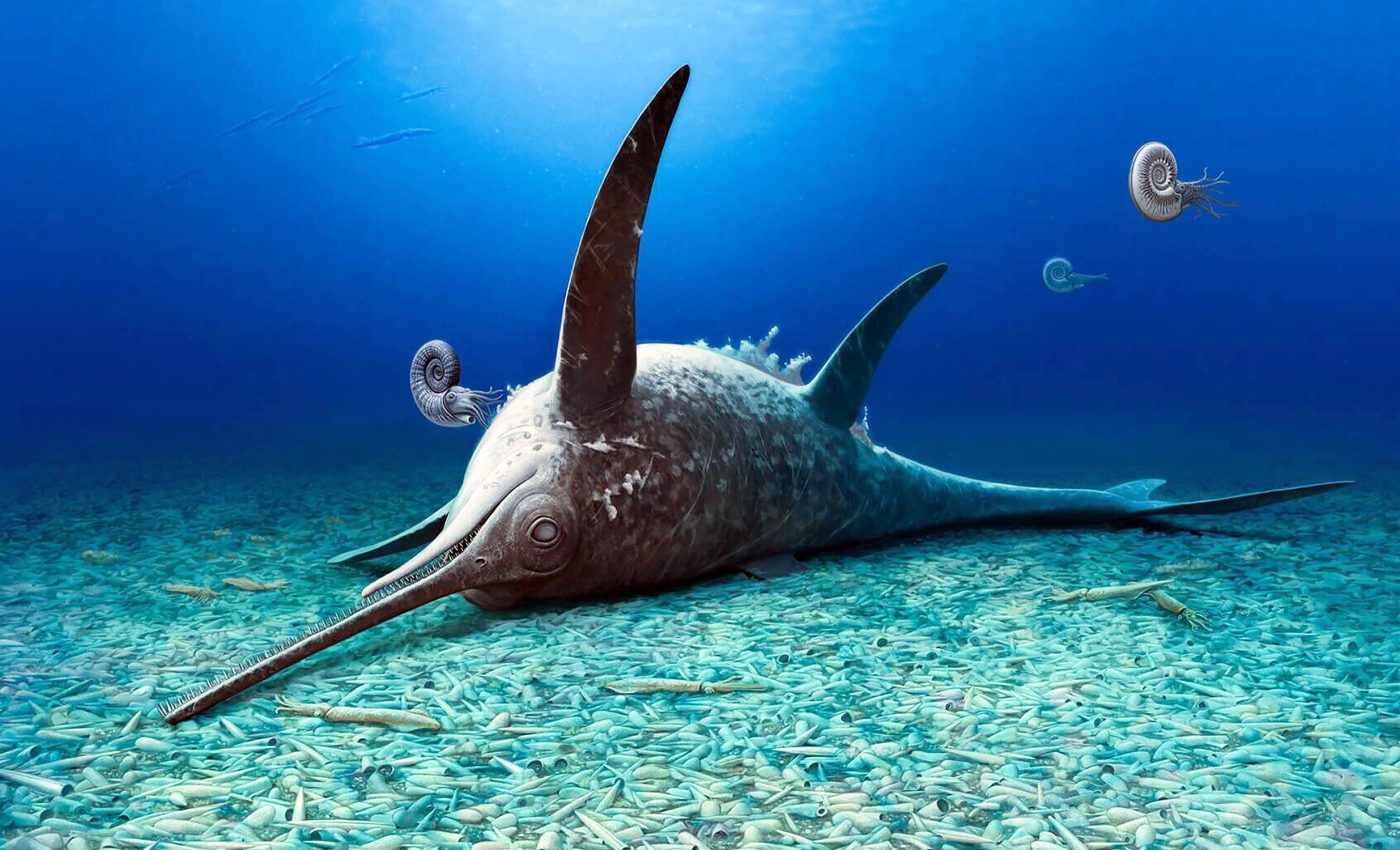

Published in the journal Fossil Record, the study introduces Eurhinosaurus mistelgauensis. Its fossils shed light on a rare group of marine reptiles that once ruled Jurassic seas.

Naming Eurhinosaurus mistelgauensis

The species name, Eurhinosaurus mistelgauensis, connects it forever to the Mistelgau clay pit. That location has produced fossils for decades, revealing creatures that lived when shallow seas covered the region.

“We wanted to highlight the scientific importance of the Mistelgau locality,” said lead author and doctoral student Gaël Spicher from Universität Bonn.

The clay pit has been studied since 1998 under the care of the Urwelt-Museum Oberfranken. Teams excavated bones, prepared them carefully, and stored them until research could be done.

From this work emerged skeletons with unusual features. Those features set them apart from all known species of Eurhinosaurus.

What the fossils revealed

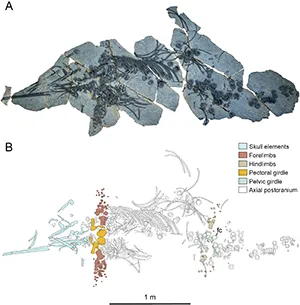

The Mistelgau fossils preserved something rare. Instead of being flattened like most ichthyosaurs, the skeletons kept their three-dimensional form.

Two nearly complete skeletons and a partial snout gave researchers a new perspective. Elements remained in articulation, allowing details of joints and ribs to be studied from angles not possible with crushed fossils.

That detail confirmed the fossils as Eurhinosaurus. The long snout and pronounced overbite stood out immediately. Yet other traits were different enough to demand closer inspection.

The Mistelgau specimens were also the youngest examples of the genus, extending its timeline deeper into the Jurassic.

Bones with differences

The skeletons showed traits not present in Eurhinosaurus longirostris or Eurhinosaurus quenstedti. The ribs were robust and round rather than slender and grooved.

The skull base had a unique shape where it connected to the spine. These differences were consistent across the skeletons, ruling out simple variation.

Body size also distinguished the Bavarian fossils from their larger relatives. The largest preserved specimen measured just over four meters (13 feet), while others reached only three and a half meters (11.5 feet).

While some Eurhinosaurus species grew to nearly seven meters (23 feet), the Mistelgau specimens were clearly smaller. Size alone does not define a species, but combined with distinct anatomy, it reinforced the case.

Injuries locked in bone

Not all surprises came from healthy bones. One rib showed abnormal fusion, known as pseudarthrosis. Another skeleton had a humerus scarred by avascular necrosis, a condition in which bone tissue dies from poor blood flow.

These conditions mirror those seen in whales and dolphins that dive deep. Such evidence hints at lifestyle. Eurhinosaurus mistelgauensis likely hunted prey at depth, risking decompression stress.

The pathologies demonstrate that even Jurassic predators paid a price when pushing their bodies to extremes. The fossils captured more than form – they preserved signs of the struggles written into life itself.

Value of Eurhinosaurus mistelgauensis

“The naming of a new species emphasizes the significance of the Urwelt-Museum Oberfranken’s fossil collections for understanding Jurassic marine ecosystems,” said museum director Dr. Serjoscha Evers, who was not involved in the study.

The collection matters because it keeps material safe for future research. Museums serve as archives where unanswered questions wait for new tools and perspectives.

Mistelgau’s fossils prove that a single locality can influence global understanding of ancient life.

A site like no other

The geology of Mistelgau explains why the preservation is so exceptional. The Eurhinosaurus mistelgauensis fossils came from the Jurensismergel Formation, a sequence of clays and marls deposited during the Upper Toarcian stage.

At that time, southern Germany sat beneath shallow seas filled with ammonites and belemnites. When carcasses sank, soft sediments buried them quickly enough to keep their bones intact.

Unlike Holzmaden’s flattened slabs, Mistelgau offers depth. The bones stayed articulated in three dimensions.

For paleontologists, that difference means entire structures can be examined in ways not possible elsewhere. Fine features of the skull, limbs, and joints have become visible after millions of years.

The puzzle of Jurassic life

The story does not end with a name. Researchers are preparing more detailed studies of the Mistelgau ichthyosaurs.

Injuries will be examined closely to reveal insights into diving behavior, survival strategies, and predator-prey encounters.

Taxonomic comparisons with other species will refine where this new form fits within ichthyosaur evolution.

Every fossil prepared at Mistelgau adds another piece to the puzzle of Jurassic life. From clay pits in Bavaria, scientists are reconstructing how ancient seas functioned – predator by predator, layer by layer.

Legacy of Eurhinosaurus mistelgauensis

What began as local excavations in the 1990s has become a global contribution to paleontology.

Mistelgau’s fossils remind us that history is never complete. Each skeleton brings a new detail, a new story, and sometimes even a new species.

The bones of Eurhinosaurus mistelgauensis carry more than shape. They reveal adaptation, record injury, and document survival in oceans that vanished long ago. With every discovery, the past becomes just a little more alive.

The study is published in the journal Fossil Record.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–