Scientists confirm that giant Earth cracks are devouring entire cities

Across the Democratic Republic of the Congo, fast-growing ground fractures are quietly reshaping cities. New research shows that more than 3.2 million people now live next to these expanding erosion channels.

These erosion channels are features that can deepen, widen, and carve through entire neighborhoods in just a few rainy seasons.

The mapping effort, led by Matthias Vanmaercke, a geographer at KU Leuven, along with Congolese partners, reveals a hazard that grows alongside urban expansion.

Dozens of rapidly developing cities are affected, and the new dataset offers the clearest picture yet of just how far these fractures reach – and how quickly they advance.

Mapping the erosion channels

These fissures are urban gullies, erosion channels that begin when stormwater cuts into loose soil and continues deepening. They can slice through neighborhoods and sever roads within a few rainy seasons.

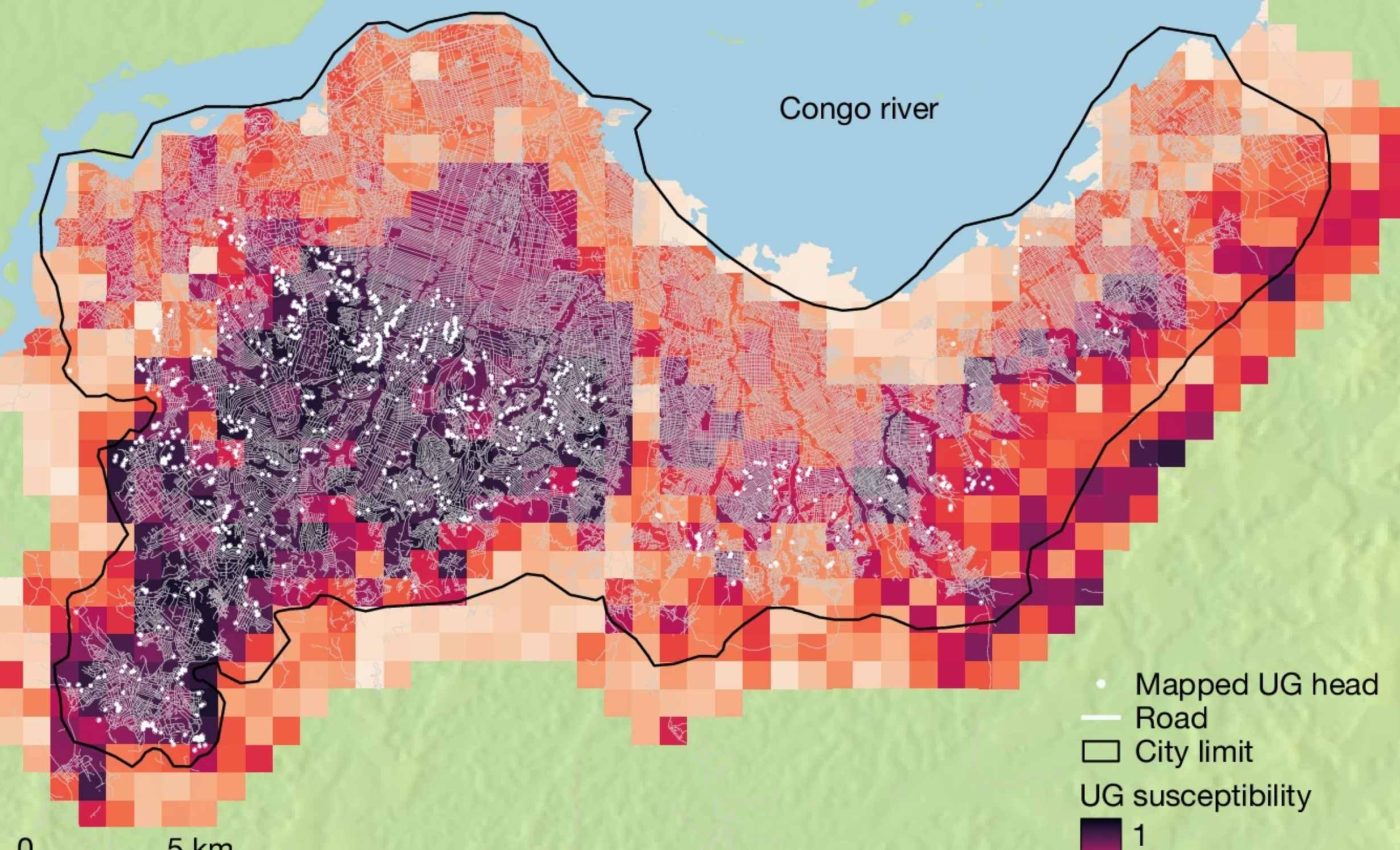

Researchers mapped 2,922 distinct features across 26 Congolese cities using recent satellite images paired with historical aerial photos.

Together, those channels stretch about 459 miles, a length comparable to the distance from New York City to Pittsburgh.

In Kinshasa alone, hundreds of separate channels carve through densely built districts, forcing emergency repairs and detours.

The dataset shows a hazard that is not a one-off event but a persistent urban process that expands with each intense storm.

Cities fuel erosion channel growth

When rain hits roofs and pavement, it becomes runoff, rainwater that flows over hard surfaces rather than soaking into the ground.

That flow races downhill, gathers in streets, and scours exposed soils where drainage is missing or clogged.

Roads matter because they collect and redirect water into narrow paths that act like flumes. Most mapped channels physically connect to the road network, so poorly drained streets can turn from infrastructure into engines of erosion during downpours.

Vegetation removal leaves bare, sandy hillsides that slough away under concentrated flow. Added impermeable surfaces, such as asphalt and concrete that block infiltration, increase the volume and speed of water that reaches vulnerable slopes.

These features differ from sinkholes, sudden collapses caused by underground voids in soluble rock. Urban gullies lengthen and widen over years, so the footprint expands even when the head of the channel appears quiet.

Risk hotspots mapped

By 2023, about 2.7 million residents lived within 328 feet of an active channel, a distance where property damage and access problems are common.

Another half million people occupied zones the authors expect to erode within a decade if nothing changes.

The exposed population roughly doubled between 2010 and 2023 as cities grew outward and upward. New construction clustered near existing hazard zones, which means today’s planning choices will lock in tomorrow’s risk.

Risk concentrates on steep, sandy plateaus and hillslopes that ring many Congolese cities. In those places, rainfall intensity and fragile soils combine with rapid development, producing the recipe for fast-carving channels after each storm.

Household vulnerability multiplies the danger because many affected neighborhoods lack formal drainage, land titles, or resources to relocate.

The result is a creeping disaster that erodes savings, trust, and infrastructure even before a wall or road collapses.

Erosion channel impact grows rapidly

From 2004 to 2023, an estimated 118,600 people lost homes as erosion channels widened or advanced into blocks that had seemed stable a few years earlier.

Since 2020, the annual displacement rate has averaged about 12,200 residents, a jump that mirrors recent surges in urban growth.

Nearly all mapped features expanded at least once in the observation window, confirming that the threat is dynamic, not static.

Most displacement stems from sidewall widening, the slow outward collapse of steep gully banks, which accounts for roughly two-thirds of uprooted households.

“It’s an underestimated and severely under-researched hazard,” said Vanmaercke. His remark captures a pattern that keeps recurring when cities outpace the infrastructure meant to guide water safely to rivers.

Looking ahead, the authors note that tropical Africa is projected to see heavier downpours in coming decades. More intense rainfall, stacked on rapid urbanization, means the same streets that move people today could channel destructive flows tomorrow.

What smarter city planning can do

Stopping channels early costs less than rebuilding after neighborhoods collapse. Stabilizing a single mature gully can exceed $1 million, a price tag that makes prevention the only workable strategy at city scale.

The first priority is to capture water before it concentrates, using upslope cisterns, terraces, and graded inlets that flow into protected drains.

Well-placed culverts, pipes that carry stormwater under roads, help prevent streets from turning into fast-moving streams.

Where channels already exist, a mix of engineered works and living cover is needed. Vegetation alone rarely holds when banks are tall, but deep-rooted plantings can lock in soil around gabions, retaining walls, or lined channels.

Urban risk plans should explicitly include disaster risk reduction, the planning that cuts deaths and losses through targeted investments.

That means mapping expansion zones, enforcing setbacks, and aligning zoning with hydrology so new streets do not pour water into the next failure.

Lessons from the erosion channels

At its core, this is physics meeting city building. Concentrated water has more power than soil can resist, so it carves a path, picks up more water, and carves deeper.

Cities can break that feedback loop by spreading water out and slowing it down before it gathers force. The science is clear, and the maps show exactly where the next cut could begin.

Local context matters, because a solution that works on one sandy plateau may fail on a clay hillside. Even so, simple actions like maintaining drains and keeping vegetation buffers around streams pay off almost everywhere.

The data give leaders a chance to act before the next rainy season. Early choices about drainage, materials, and road layout will decide whether homes stand or fall when the clouds open.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–