Scientists find the skeleton of a killer crocodile that hunted dinosaurs 70 million years ago

Seventy million years ago, a crocodile relative almost as long as a compact car stalked dinosaurs in southern Argentina. Now, scientists have uncovered its fossilized bones, showing that this meat-eater was one of the top predators in its ancient ecosystem.

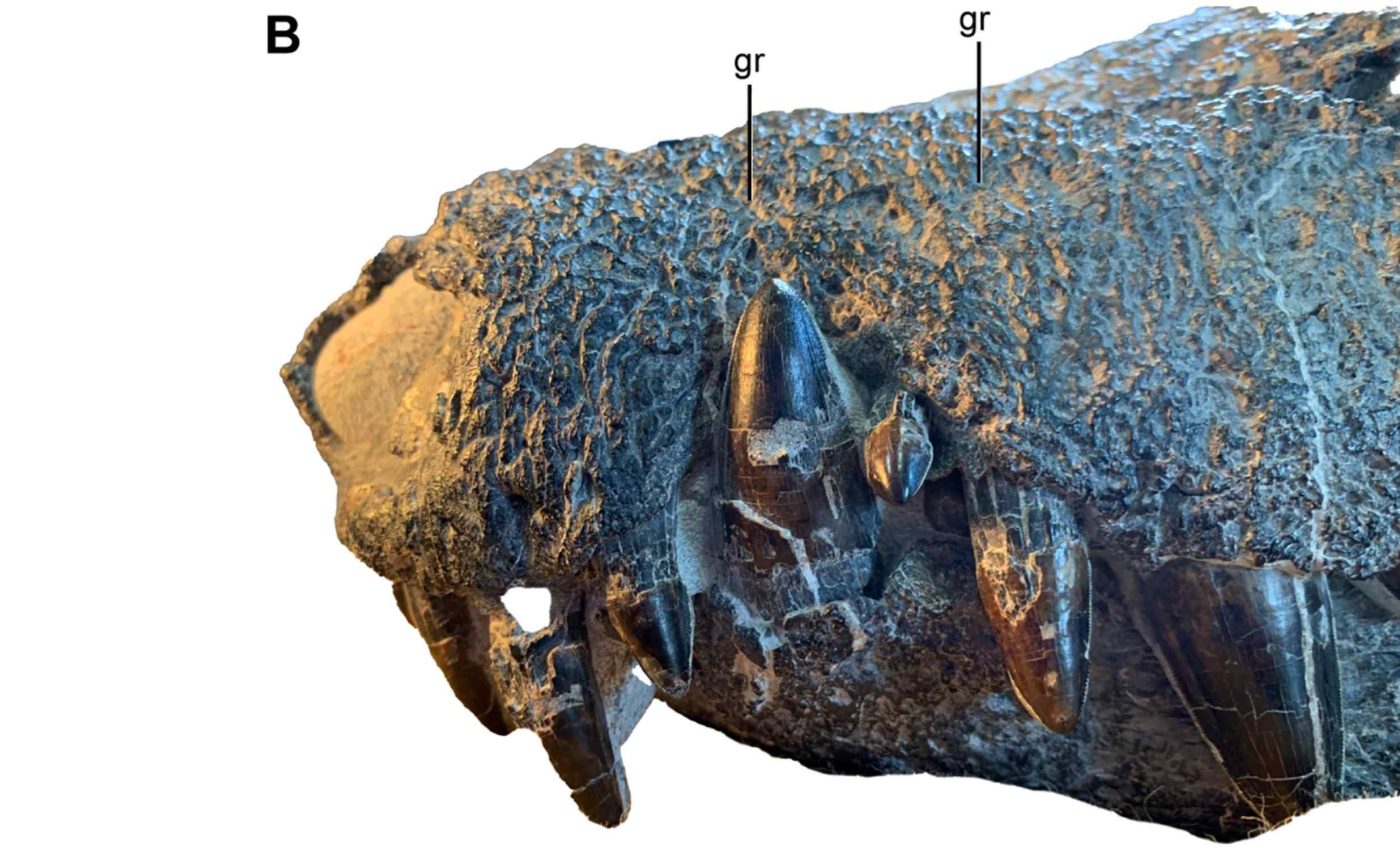

Kostensuchus atrox stretched about 11.5 feet (3.5 meters) and weighed roughly 550 pounds. It had a huge skull, blade edged teeth, and strong limbs.

The fossil comes from the Chorrillo Formation near El Calafate in Patagonia and reveals a new kind of dinosaur-hunting crocodile cousin.

Killer crocodile from Patagonia

This predator belongs to a group called crocodyliforms, which are ancient reptiles related to modern crocodiles and alligators but on separate evolutionary branches. Its bones show a stocky body, upright limbs, and a skull that looked built for power rather than stealth.

The work was led by Fernando E. Novas, a paleontologist at the Félix de Azara Natural History Foundation at Maimónides University (UMAI) in Buenos Aires. His research focuses on ancient Patagonian ecosystems and the predators that shaped them.

In the original study the team shows that this animal had the skull and teeth of a powerful carnivore. They classify it as a hypercarnivore – an animal whose diet is mostly meat.

The skull alone was about 1.6 feet long, with deep jaws able to crush the bones of medium-sized plant eating dinosaurs. Its pointed, serrated teeth were ideal for puncturing and slicing through the flesh of sizable prey.

A member of the research team noted that the animal filled a role similar to the top hunters seen among big cats today.

The group identified Kostensuchus as the second largest predator in its environment, surpassed only by the massive theropod Maip.

Unusual body for a croc cousin

Kostensuchus did not look exactly like today’s river crocodiles, even though both lineages share a similar overall body plan. Its nostrils faced forward, and its eyes sat on the side of the skull, not high on top for hiding just below the water.

The limb bones suggest a more upright posture than living crocodiles, with the legs tucked partly under the body instead of sprawling out.

That stance would have helped it move more easily on firm ground, where many of its likely victims spent their time.

That kind of repeated change is known as convergent evolution. It occurs when unrelated species evolve similar traits under similar conditions.

In other words, different croc lineages kept shifting between life mostly on land and life split between land and water.

Life on a Cretaceous floodplain

The rocks that yielded the skeleton were laid down in the late Cretaceous. Geologists call that slice of time the Maastrichtian, the final stage before the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact.

At that time the region held humid, freshwater floodplains, with rivers, shallow lakes, and thick vegetation. Today, the region is a cold steppe.

Fossils from the same layers record small, plant-eating dinosaurs, frogs, turtles, and early mammals, including a distant relative of the modern platypus.

By adding a large predator to this southern ecosystem, Kostensuchus shows that big, meat-eating croc relatives reached high latitudes just before the dinosaurs vanished. A recent feature highlighted how this fossil helps fill a gap in the Patagonian fossil record.

Winners and losers in mass extinctions

Other researchers have looked at dozens of fossil croc skulls to test which kinds of diets survive global crises. They find that generalist feeders tend to persist when specialist meat eaters vanish, a pattern seen in croc line evolution across several extinctions.

Kostensuchus fits the vulnerable side of that pattern, because its body was large and its diet narrow. Fossil evidence suggests that many big terrestrial croc relatives disappeared at the end of the Cretaceous, while only smaller forms survived. .

Fossils and crocodile evolution

Over their 200-million-year history, croc relatives have ranged from dog-sized plant eaters to huge marine hunters, not just river ambush predators.

Work on body size patterns shows repeated shifts between small and large forms, rather than one steady trend.

Kostensuchus belonged to a family called peirosaurids, which were stout-snouted crocodyliform predators from southern continents. They are known from several parts of the former southern supercontinent, Gondwana.

The well preserved skeleton gives scientists their first clear view of a big member of this group, from snout tip to shoulder girdle.

Researchers now plan to sample chemical clues from the teeth, measuring isotopes – versions of elements with different atomic weights that record water and food sources.

Scans of the bones can also reveal how fast the animal grew and whether it suffered injuries or disease during its life.

Lessons from Kostensuchus

Finding a nearly complete skeleton lets scientists go beyond isolated jaws or teeth when they reconstruct how ancient predators moved and hunted.

Kostensuchus shows one additional way that the crocodile lineage experimented with body shapes, sizes, and lifestyles before settling into the forms we see today.

For students and researchers alike, this fossil is a reminder that even familiar animals have deep, varied histories that science is still uncovering.

By studying predators such as Kostensuchus, scientists can understand better how ecosystems respond when climates shift, food webs change, or sudden disasters strike.

The study is published in PLOS One.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–